Soleil Burke has fond memories of her childhood on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation in northwestern Nevada, a tight-knit community located 35 miles northeast of Reno.

“It is a safe and nurturing community with barely any light pollution,” she says. “I grew up watching clear, bright stars at night and beautiful sunsets from our backyard. You couldn’t get that anywhere else.”

But amid this idyllic existence, an empty chair at the dining table served as a quiet reminder of her father; a gregarious and warm man she now remembers only faintly. His life was tragically cut short, leaving her mother a young widow with three small children.

A decade or so later, thanks to the unwavering support and encouragement of her mother, and grandmother who helped raise her and her siblings, Burke graduated from high school near the top of her class, while also earning some dual college credits. After carefully evaluating what she refers to as “strong agriculture colleges,” she chose to attend the University of Nevada, Reno's College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources to pursue a bachelor's degree in wildlife ecology and conservation.

Thanks to the Native American Fee Waiver provided by the Nevada System of Higher Education and various scholarships, including financial support from the College’s Tribal Students Program at the University, Burke’s mother can rest easy knowing that tuition and housing at the University’s Indigenous Living Learning Community, are covered. This University housing option offers Tribal students opportunities for mentoring, tutoring, internships, graduate school options, networking and job placement.

Preparing Tribal high school students for college

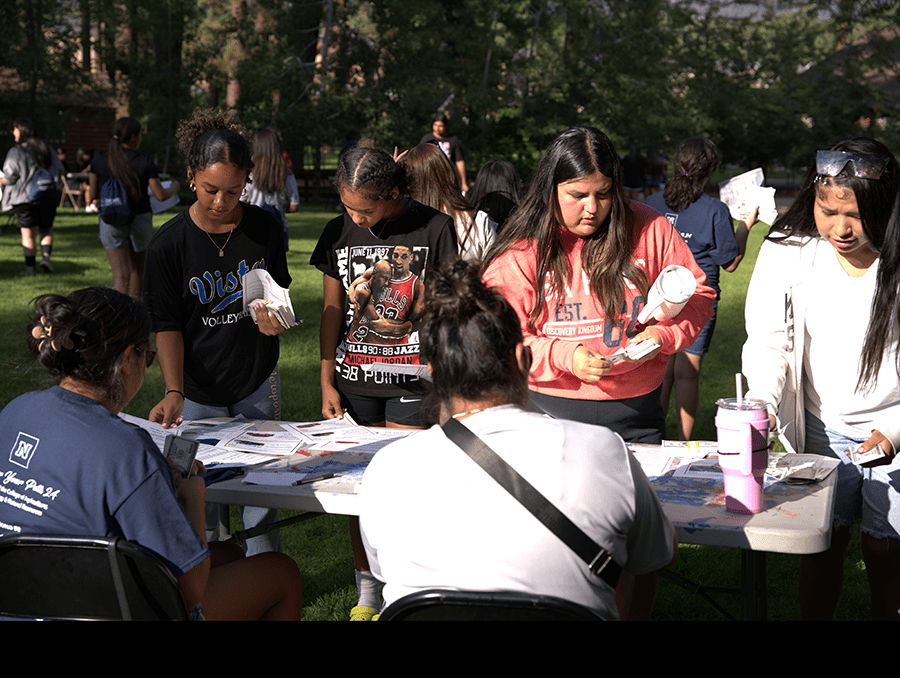

Burke first learned about the College at the Discover Your Path Tribal College Prep Camp in 2017, a week-long summer camp established by the College’s Tribal Students Program where Tribal high school students learn about how to apply to college and career options. Despite her initial reservations, her grandmother, who saw the camp’s advertisement on Facebook, encouraged her to attend. Since then, Burke participated each year in the annual late-July camp, held at the scenic Nevada State 4-H Camp in Lake Tahoe.

Kendal Navajo, whose father is Navajo and mother is Canadian Okanogan, also attended the camp each year from its inception. Now an undergraduate in the College, she is pursuing a degree in rangeland ecology and management. Navajo says the isolation caused by the pandemic, coupled with her natural shyness, made her even more withdrawn after battling COVID-19. Concerned for her daughter’s well-being, Navajo’s mother, who also learned about the camp through social media and emails from the Clark County School District’s Indian Education Opportunities Program, encouraged her to attend the camp and even volunteered as a chaperone.

"The camp made me feel comfortable, as if I were with people who truly understood how I felt," Navajo said. "Being around other Natives in an interactive setting helped me feel at ease and more open to sharing my experiences because we could relate to each other."

Unlike Navajo who grew up in Las Vegas, many Tribal students have been raised in isolated reservations and often struggle to adjust to the bustling atmosphere of a large university.

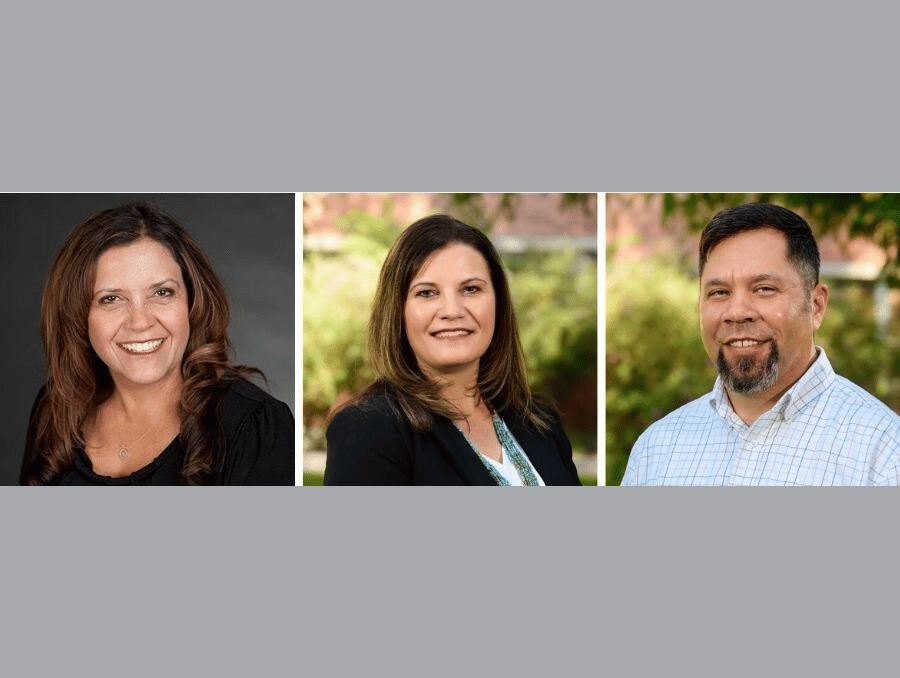

“At the camp, we want to help students come out of their shells; build their confidence; and provide them with the social, financial and academic information they need to be more informed about college and to ease their transition,” said Kari Emm, a specialist with the College’s Tribal Students Program who also administers the camp. “We want them to appreciate the value of post-secondary education and be aware of all the university resources available to support their personal and academic success.”

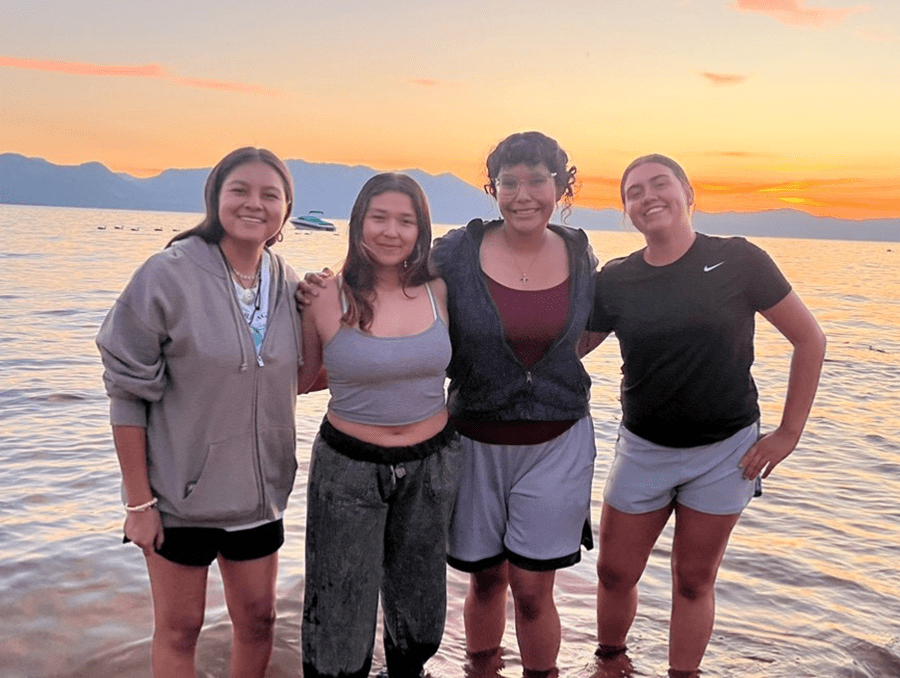

To Burke, Navajo, Serenity Phelps and Isabella Smokey, all alumni of the camp and first-year students at the College, Emm is nothing short of a hero. They all agree on one thing: she and her team of coordinators at the Tribal College Prep Camp have been invaluable mentors, guiding them through the complexities of applying to colleges and offering crucial information to which many first-generation students might not otherwise have access. Emm, who is a member of the Yerington Paiute Tribe and grew up on the Walker River Paiute Indian Reservation in Schurz, Nevada, knows firsthand how difficult it is for Native students to access higher education. Through her own experiences, she has developed a passion for underserved student populations.

Smokey, a Native Wašiw who lives in Phoenix, Arizona, says that she is exhilarated to be following in the footsteps of her mother, an uncle and an aunt by attending the University of Nevada, Reno. She is enrolled in the College and hopes to pursue a degree in environmental science.

Tribal Students Program: Specialized support for Tribal students

The four first-year students will now be part of the Tribal Students Program where they will benefit from scholarly and professional networking opportunities, professional development seminars, and financial and housing assistance at the University’s residential housing for the Indigenous Living Learning Community. The program also coordinates internships and job placements with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, other land-grant universities, and federal and local indigenous community development programs, among others.

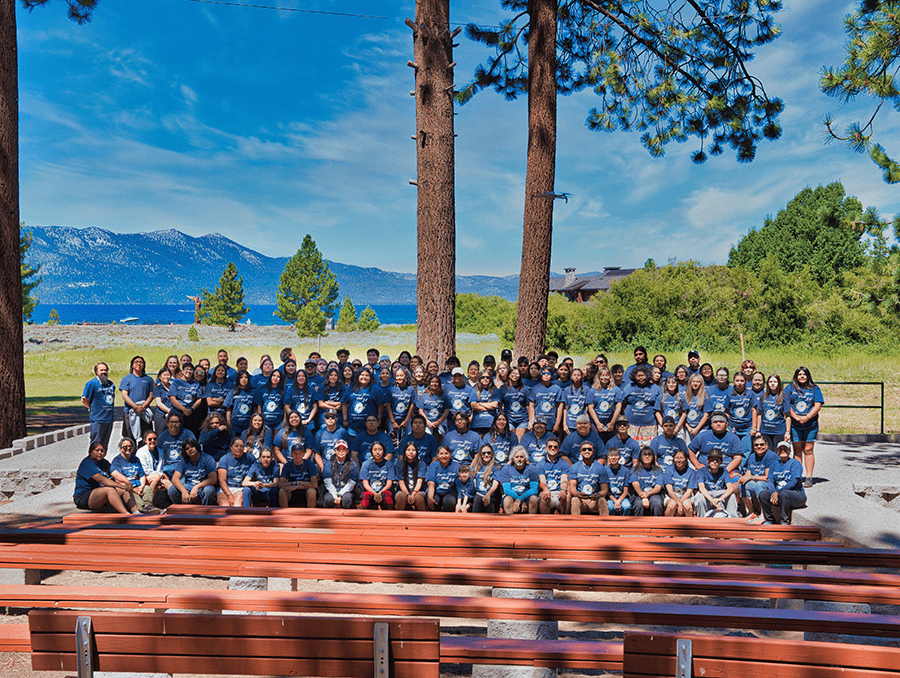

The Tribal College Prep Camp has grown in popularity since its inception. Applications have surged nearly seven-fold, growing from 17 students in 2022 to more than 110 registered this year, and drawing students from other states, including Oklahoma, California and Arizona. The camp includes a series of breakout sessions where representatives from various academic programs from across the University present their degree programs. The camp’s itinerary features a blend of other activities, including polar bear plunges, cabin chores, beach time, cultural performances and games.

Phelps, whose father is a Native of the Duckwater and Yomba Shoshone tribes in Nevada, attended the camp for the first time this year. She will be joining the College to pursue a degree in veterinary science. Upon graduation, she intends to follow in the footsteps of her grandfather and uncle by joining the military, where she eventually hopes to train as a military veterinarian.

pivotal moment at the camp for Phelps was meeting Daniel Coen, a 25-year military veteran. Coen, the American Indian student coordinator with the Tribal Students Program, leans on his military background to provide mentorship, counseling and guidance to the students at the camp. He and Staci Emm, Extension professor, co-founded the camp when they realized a significant disparity in college preparedness between Tribal and non-Tribal students.

“What we discovered is that many of our Tribal students often don’t know what to expect of college,” Coen said. “Some end up dropping out due to being homesick or because they are unprepared for the academic demands and unaware of the excellent academic support resources offered by the University. That is why our camp is so crucial. It is where we begin preparing them to succeed from day one.”

Future faculty training to bridge gaps for Tribal students

Kari and Staci understand these challenges well, having grown up on the Walker River Reservation. They are aware of the skepticism and sometimes extreme trust issues that pervade the students, holding them back from connecting with their new environment. Together with Coen, the Emm sisters with the College’s faculty have often assumed a parental role over the students.

Broad support drives Tribal Students Program and prep camp

Most of the University’s academic programs contribute annual funds to the Tribal Students Program, supporting initiatives such as the camp. A few years ago, with the backing of the College’s Dean, Bill Payne, the College donated a house previously reserved for offices to accommodate upper classmen Indigenous students. The College funded the remodeling, with the Tribal students dedicating countless hours to transforming the house into a home with free rent and utilities for the students. The house is conveniently located near the Experiment Station’s Desert Farming Initiative, which offers regular internships to Tribal students.

“This is a form of scholarship that offsets the cost of attending college for Tribal students in agriculture-related programs,” Coen said. "It also frees up funds to accommodate more of our students’ Indigenous housing.”

Additionally, the University’s Graduate School provides scholarships in the amount of $45,000 a year as matching funds toward federal funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, which supports the Tribal Students Program.

Talented, diverse and driven

The four first-year students from the Tribal College Prep Camp are vibrant and enthusiastic. Phelps excels in a variety of sports and Smokey is an aspiring artist. Burke is a passionate scholar, and Navajo is a budding violinist who has mastered her part in Anastasia, the Broadway musical, and once performed at the Las Vegas-based Smith Center for the Performing Arts with the Las Vegas Youth Orchestra.

Their bonding experience at the camp has engendered a form of sisterhood that they say they hope to sustain beyond college.

"My camp friends and I feel grateful to the University for providing such a great learning and bonding camp experience,” Navajo said. “Someday along the way, we all hope to bring back what we have gained in school into the world to make a real difference in our communities.”

Program supported by friends, family and the federal government

The creation of the Tribal Students Program was also made possible by the Native American Agriculture Fund, which allowed their private funds to match the federal grant award for the creation of the College’s Tribal Students Program in 2020. The program has continually expanded with their support and collaboration of the University’s colleges and private donors.

Donations for the Tribal Students Program and the Tribal College Prep Camp come from the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources; Extension; the Desert Farming Initiative; and state agencies such as the Nevada Department of Education’s Indian Education Program and the Native Community Youth Project. The program also receives support from the UNLV William F. Harrah College of Hospitality’s Tribal Gaming Program and private donors such as Frances C. & William P. Smallwood Foundation and Nevada Gold Mines. Other annual supporters within the University include the College of Education & Human Development, College of Engineering, College of Liberal Arts, College of Science, Office for Prospective Students, Orvis School of Nursing, Reynolds School of Journalism and School of Public Health.