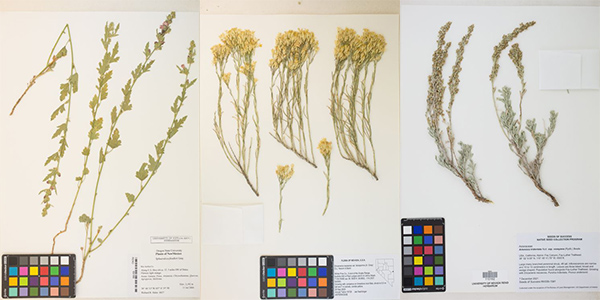

The Great Basin spans roughly 200,000 square miles, and life in the region depends heavily on the widespread shrubs in the landscape, primarily rubber rabbitbrush and big sagebrush. The complex topography of the Great Basin, and the western US more generally, provides plants with plenty of opportunities to practice adapting to new environments and expand their ranges.

Along with their colleagues, scientists from the University of Nevada, Reno recently published research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showing that environmental factors such as precipitation, temperature and elevation are very good predictors of where closely related plant species form hybrids: in environments that are intermediate to the habitats of parent species. This means that hybridization, which is the combination of genetic material from previously isolated lineages in the offspring, could help plants expand their distributions into new areas, and even help species adapt more quickly to changes in climate. When closely related species have not evolved complete barriers to reproduction, hybridization between them can create individuals and populations with genetic variation that is intermediate between the two parental species, like the intermediate environments of their parent plants. Hybridization can also maintain or increase genetic diversity, which may allow hybrids to thrive and adapt to their niche environments.

"Plants have great capacity for adapting to changing climates and environments."

“Genetic diversity is the agent that natural selection acts upon,” Trevor Faske, ’24 Ph.D. (Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology), co-lead author of the paper, said. “That's where local adaptation happens. You need variation across genetics or traits for adaptation to happen.”

“Theoretically, genetic diversity is among the best predictors of how quickly and how well adaptation works,” Professor Thomas Parchman, who advised Faske during his doctoral studies, said. “It's basic evolutionary biology with direct implications for how plants might respond or how they might be managed in a changing climate.”

Where are the hybrids?

Hybridization between species is often influenced by two factors in nature: physical proximity to one another and adaptation to specific environmental conditions like the climate (temperature and precipitation) of a region, which is strongly influenced by elevation. The researchers identified multiple “mosaic hybrid zones,” where environmental characteristics make it likely for hybridization to occur. These mosaic hybrid zones are scattered throughout many locations across the west, indicating that hybridization is a common and potentially important way for plants to interact and evolve.

Parchman and Foundation Professor Elizabeth Leger, both faculty in the Department of Biology, collaborated on a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant to study variation across six ecologically significant plants in the West, including rabbitbrush and sagebrush. As the researchers studied the genetic composition of these plants, they began recognizing relationships between where hybrids were located and the environmental conditions the plants inhabited.

“We started to see these consistent patterns across these really important systems for restoration,” Faske said.

At this point, Faske was finishing his doctoral degree and had secured a job with the U.S. Geological Survey. He began working with Rob Massatti, co-lead author on the publication and research ecologist at the USGS.

“For our work with several other species, we noticed the same predictable pattern,” Faske said.

As they studied the relationship more, they were able to predict whether a plant on the landscape was one of the parental plants or the hybrid of the parentals based solely on the environmental data — a pattern they could confirm with genomic data.

“Rob and Trevor came up with the idea of thinking about the area of occupancy based on the environmental models that predicted where hybrids occur and looked at how the area of occupancy would change over time based on climate change,” Parchman said.

Faske and Massatti reached out to Parchman and Leger and presented their hypothesis (Faske joked, “It’s like a science project with my entire academic lineage!”). The data was compelling.

“In the case of these shrub species, environmental variation does an amazing job of predicting where you're going to find species A, species B, or where you're going to find hybrids,” Parchman said.

“And we can predict it across the entire landscape,” Faske said. “And we can do it across three different species. So this pattern is likely to be playing out repeatedly across many species in the West due to the history of glacial cycles and the topography of Western landscapes.”

Hybrids may be a crucial tool for future restoration efforts

The researchers noticed that the hybrids occupied spaces where neither of the parental species were found.

“If you were to calculate the overall range of the species, just using the two parental species, it's much, much smaller than when you include the hybrids,” Faske said.

Despite the vast regions sagebrush, rabbitbrush and globemallow, another plant studied in the research, inhabit, there is significant fragmentation of their habitats taking place.

“Plants have great capacity for adapting to changing climates and environments,” Faske said. “They've been doing it for millions of years. I would guess that if plants are left alone to do their thing and the environment changes, some species may do an okay job at adapting to their new environment. But then when you have habitat fragmentation, urbanization, changing fire regimes and all these other factors impacting them, they can't really keep up with all of it. And habitat fragmentation is a big one, especially when you're talking about how it disrupts gene flow across their distributions.”

The hybrids are a beacon of hope, though.

“The hybrids are actually creating connectivity across the landscape, which allows genetic diversity to be maintained and can help mitigate things like population decline in changing environments,” Faske said.

The scientists’ findings suggest that hybridized plants could play a key role in how restoration experts decide what native seeds to plant after disturbances like wildfire.

Since this publication, both Faske and Massatti have left their federal research positions at the USGS to start a nonprofit, the Landscape Stewardship Collective, with the continued goal of using evidence-based science to inform the restoration and management of public lands. The Landscape Stewardship Collective will be partnering with land managers like the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service, as well as with seed suppliers who the land managers purchase seeds from. One of the first goals of the newly founded nonprofit will be to create individual genetic management plans for roughly 30 “high priority” restoration species from around the western US, including some of the species from their recent publication.