Long assumed by some to have been diluted and washed away over time, mercury contamination from 19th-century gold mining is still moving through Nevada’s Carson River, with levels in some waterfowl reaching up to 60 times federal safety thresholds for human consumption, according to a new study.

The toxic metal remains locked into riverbanks and sediments, where flood years remobilize and reintroduce it into the aquatic food web, researchers from the University of Nevada, Reno's College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources found.

The study analyzed more than 15 years of feather samples from resident wood ducks, a nonmigratory species that lives in the Carson River watershed year-round and is commonly hunted for food. The analysis revealed up to 66 micrograms per gram of methylmercury, a highly toxic form of mercury produced by bacteria, far exceeding the Food and Drug Administration’s safety level of 1 microgram per gram and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s limit of 0.3 micrograms per gram for human consumption.

“This mercury didn’t disappear — it’s still there, and high water actually makes the problem worse,” said Perry Williams, the study’s principal investigator and associate professor in the College’s Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Science. “Nevada has no waterfowl consumption advisories despite these elevated levels, raising serious human health concerns.”

Other researchers on the project include Mae Gustin, Morgan Byrne and Chris Nicolai. Gustin is co-principal investigator on the project and professor of environmental geochemistry, who has studied the effects of mercury pollution on ecosystems for three decades. Gustin and Williams also conduct research as part of the University’s Experiment Station. Byrne is an alum who collected and analyzed environmental mercury samples as part of her master’s thesis and is now a wildlife biologist for a consulting firm. Nicolai is a waterfowl biologist formerly with Delta Waterfowl and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. He led the long-term monitoring of wood ducks along the river and provided thousands of feather samples collected over 16 years from both adults and ducklings.

The study was supported by the Nevada Department of Wildlife, the Nevada Waterfowl Association and a U.S. Department of Agriculture Hatch grant, with additional support from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Delta Waterfowl, Ducks Unlimited and Four Flyway Outfitters.

Published in the journal Science of The Total Environment, the study traced how mercury stored in Carson River sediment is reactivated during high-flow events, enters the aquatic food web, and accumulates in resident wood ducks and potentially in people who eat them.

Mercury stored in riverbanks is remobilized during high flows

Contrary to the assumption that time erases pollution, mercury does not break down over time. Instead, the study found that in the Carson River, it remains bound in riverbanks and sediment, where it can be released during high-flow and flood events. These conditions mobilize both total mercury and methylmercury, a more toxic form that can cross the blood-brain and placental barriers and is linked to neurological damage.

“Floods don’t just move water. They wake up the mercury that’s been sitting in these riverbanks,” Gustin said. “The wet‑dry cycles create low‑oxygen conditions that supercharge microbes and push them to convert mercury into this toxic methylmercury.”

Aquatic foods are the primary source of mercury exposure for wood ducks

To pinpoint how wood ducks are exposed, the researchers compared mercury levels in aquatic foods, including duckweed and invertebrates such as worms, insects and snails, with land-based corn and Russian olives. Aquatic sources showed far higher mercury levels, with invertebrates, a preferred food during breeding and brood-rearing, containing three times the Food & Drug Administration’s safety limit for seafood.

“These findings help identify when wood ducks face the greatest mercury exposure, particularly during early life stages, that may influence long‑term health,” Byrne said.

Ducklings carry higher mercury levels than adult birds

The study also found mercury levels roughly three times higher in young wood ducks than in their mothers, driven by both inherited and post-hatch exposure.

“Exposure begins before they hatch,” Williams said. “Mercury stored in adult females is transferred into developing eggs, giving ducklings an initial mercury burden at birth. After hatching, ducklings feed heavily on aquatic invertebrates, which we found contain up to three times more mercury than federal safety limits.”

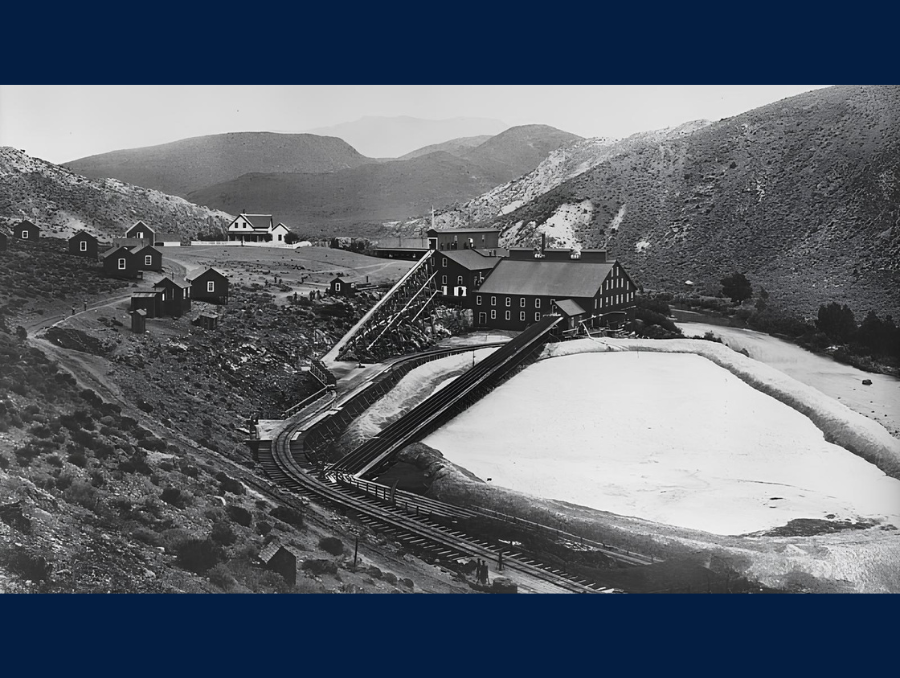

Building on earlier research, scientists have documented some of the highest streambank mercury concentrations ever measured in a natural ecosystem in the lower Carson River. Designated a Superfund site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1990, the 330‑square‑mile region spans more than 130 miles of river across five Nevada counties and remains on the National Priorities List for long‑term cleanup and monitoring.

Why wood ducks?

The research team selected wood ducks because they remain in the Carson River watershed year-round, making them reliable indicators of local mercury exposure rather than contamination picked up during migration.

Environmental samples, including duckweed, invertebrates and river sediments, were collected and analyzed for total mercury and methylmercury using a specialized mercury analyzer. Advanced statistical models then linked mercury in feathers to levels in edible breast tissue, accounting for natural variation and measurement uncertainty.

“Though not a perfect proxy for breast muscle, feathers were easier to collect and ethically sustainable,” said Gustin, the study’s lead mercury analyst.

A “wicked” ecological management problem

The researchers describe mercury management in the Carson River as a classic “wicked problem.” High-flow years mobilize mercury, but they also support agriculture and are linked to stronger waterfowl reproduction. Reducing flows could limit mercury exposure, but at significant economic and ecological costs.

“In the near term, consumption advisories for waterfowl are one of the most realistic tools available,” Williams said. “They don’t solve the contamination, but they do give people the information they need to make informed choices.”