About 125 years ago, one of the nation's first federal land reclamation projects created an irrigation network that tapped the Truckee and Carson Rivers, channeling water to a little-known town 60 miles east of Reno. No longer a dusty crossroads, Fallon is today known as the "Oasis of Nevada" – a bustling agricultural hub and one of the nation's leading producers of teff, an ancient Ethiopian grain that thrives with minimal water and is gluten-free.

Teff, valued as a high-quality forage, was first introduced to west-central Nevada in 2007 as an experimental crop with support from University of Nevada, Reno Extension. At the time, livestock feed farmers were struggling with the financial toll of growing alfalfa, a water-intensive forage, during a period of record-low rainfall.

Jay Davison, then an alternative crop and forage specialist with Extension, met a producer looking for Nevada farmers to grow 500 acres of teff. The grain would be his; the forage, a benefit to the livestock growers. Davison gathered 36 forage farmers from around Fallon to hear the pitch.

After a spirited presentation, Davison scanned the room, hoping for interest. He was met with silent skepticism.

"We didn't have a single taker," Davison said in an earlier interview. "So, I asked a friend of mine if he could plant a couple of trial acres on his land. He said, 'Sure, let's do it.'"

Just like that, Nevada's teff acreage grew from seven trial acres to 100 in a little over a year.

What began as a small-scale forage experiment soon caught the attention of University scientists who saw in teff not just a crop, but a climate-smart solution. They began studying the grain in search of high-yielding, drought-resistant varieties to help regional farmers boost production and conserve water amid a changing climate.

What do you mean, changing climate? Ask any farmer

A key player in Nevada's teff industry is Desert Oasis Teff & Grain, a Fallon-based operation run by longtime growers John Getto and Dave Eckert. They've been cultivating teff since 2009, when Davison first introduced them to the grain's potential.

Today, they grow teff exclusively for grain on their 800-acre farm, supplying a growing market for gluten-free products.

Teff seeds, one of the tiniest among cereal crops, pack a nutritional punch. Despite their size, they're rich in protein, fiber, iron and calcium, making them a powerhouse grain for both traditional and gluten-free diets. Photo by Claudene Wharton.

Water remains their most expensive input. Every field in Fallon must be irrigated, as the region receives just five inches of rainfall annually. With water prices continuing to rise, maintaining profitability becomes more difficult each season.

Still, Getto and Eckert remain optimistic. Despite ongoing production challenges, they believe the University's teff research could provide the breakthrough they've been waiting for.

From trial plots to genetic breakthroughs: New lines show 60% yield increase

A recent breakthrough came from researchers at the University's College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources. John Cushman, a plant biochemist and professor in the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, and Juan Solomon, an agronomist and associate professor in the Department of Agriculture, Veterinary & Rangeland Sciences, completed greenhouse screening of 368 teff accessions provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Both researchers are dryland agriculture experts, who also conduct research through the College's Experiment Station.

Following two years of field trials at the Experiment Station's Main Station Field Lab, the researchers narrowed the group to 20 promising accessions. Further evaluation identified five or six superior lines capable of producing up to 60% more grain per acre than Dessi, the commercial teff variety currently grown in Nevada.

"The trajectory of our research is a potential game-changer for teff farmers, who could improve their grain yields while using the remaining biomass for animal feed after harvest," said Solomon, the study's co-principal investigator and lead agronomist. "Our aim is to eventually release varieties that are more productive, adaptable and economically viable."

The findings could have broader implications across the western U.S., where irrigation is essential for teff production, but water is increasingly scarce.

"The biggest surprise was the sheer diversity in traits we evaluated – far more than we expected," said Cushman, the study's principal investigator and plant molecular biologist. "Some accessions significantly outperformed the most commonly used teff varieties, suggesting we've only begun to tap into teff's genetic potential."

The researchers are also working to develop a shorter, sturdier teff variety to reduce lodging – when plants fall over before harvesting due to the weight of their seeds.

"Teff can grow as tall as a person and often lodges under the weight of its grain, reducing its harvestability," Cushman said. "If we can shorten and strengthen the stem, we can increase the ratio of seed to overall biomass."

University teff research gaining ground in scientific literature

The researchers' latest findings were published in Frontiers in Plant Science through a collaboration with then-doctoral student Mitiku Asfaw Mengistu, the study's lead author, and Won Cheol Yim, associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, who provided bioinformatics support.

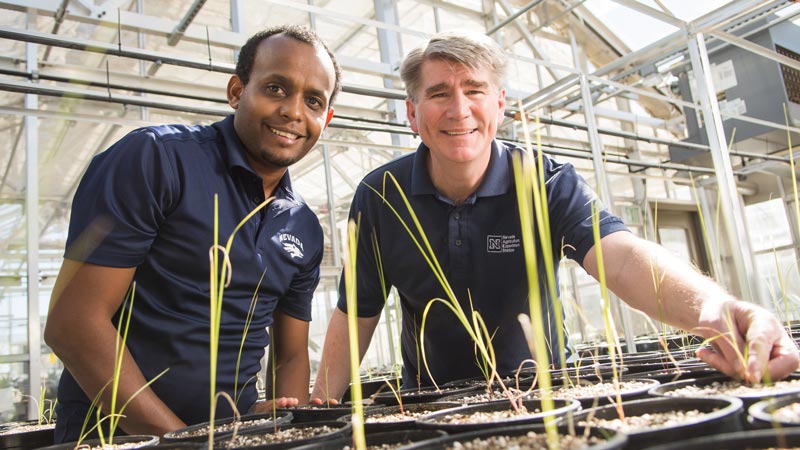

Graduate Student Mitiku Asfaw Mengistu, left, and Professor John Cushman study teff to identify which traits help increase yield while being drought resistant. Photo courtesy of Nevada Silver & Blue.

Associate Professor Juan Solomon studies grassland ecology and sustainable grazing systems. His work includes evaluating drought-tolerant forage crops and developing climate-resilient feeding strategies for ruminant livestock in semiarid conditions. Photo by Robert Moore.

Associate Professor Won Cheol Yim is a geneticist in the Molecular Biosciences Graduate Program. His lab is focused on plant genomics, studying how genomes are organized and how genome structure affects gene expression, phenotypes and genomic plasticity. Photo by Robert Moore.

Mengistu, now a postdoctoral fellow with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service, focused his Ph.D. dissertation on four key areas: expanding teff's genomic resources, identifying and characterizing drought tolerance, assessing phenotypic diversity, and exploring genome editing to improve productivity — skills sharpened through his involvement in the project. He said he was equally surprised by the extent of phenotypic diversity in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's teff collection.

"Teff hasn't received much scientific attention — it's often called an orphan crop," he said. "Our work is helping fill that gap and lays a foundation for future improvement."

While the research community is beginning to take notice, teff's appeal is also growing among U.S. farmers and consumers.

Orphan no more: Teff's growing appeal in the U.S.

Long a staple in Ethiopia and Eritrea, with some archeologists tracing its East African origins as far back as 4000 B.C., teff eventually made its way to the United States.

Injera, a spongy flatbread made from teff flour, is a staple in Ethiopian cuisine. Traditionally used as both a plate and utensil, injera is served with stews and vegetables and plays a central role in daily meals across Ethiopia. Photo by Claudene Wharton.

Now grown in at least 25 states, with Nevada among the top producers, teff is proving to be a smart financial choice for some of the state's farmers. Its seeds are relatively inexpensive and yield a faster, more abundant harvest. Just two pounds are needed to plant an acre, compared to 20 pounds for alfalfa. Teff uses only one-third to one-half the water of alfalfa each season, recovers well from drought, and requires just 50 to 60 pounds of nitrogen per acre — far less than wheat and other small grains.

Teff is not only valued for its agronomic advantages but also is enjoying a surge in popularity due to its rich nutritional profile, especially among health-conscious individuals and people on gluten-free diets.

Teff contains all essential amino acids and is rich in fiber and minerals. According to the Nevada Department of Agriculture, one cup provides 62% of the recommended daily value of dietary fiber, 82% of iron, 89% of manganese and 83% of phosphorus. Its unique starch supports beneficial gut bacteria, making it ideal for people with diabetes.

Teff's rich nutritional profile

1

cup of teff

62%

daily

fiber

82%

daily

iron

89%

daily

manganese

83%

daily

phosphorus

With teff gaining traction among both producers and consumers, University researchers are now focused on the next phase: scaling its potential through advanced field trials.

Advancing teff research: Next steps toward higher yields

Following successful greenhouse screenings and on-farm trials, researchers Cushman and Solomon are preparing for a three-year, multilocation testing phase, pending grant approval, to evaluate the most promising teff accessions in a range of soil and climate conditions.

The trials are scheduled to run across three consecutive growing seasons, from late May through early October each year. The primary objective is to develop cultivars capable of yielding up to 2,000 pounds of grain per acre, double the output of Dessi.

These multilocation trials will generate essential data on the stability and adaptability of the new lines, potentially expanding teff production opportunities in Nevada and other Western states where the crop is gaining interest.

"These field trials allow us to confirm which traits truly enhance performance under real-world conditions," Cushman said. "That's the foundation for achieving meaningful genetic improvements in crops like teff."

- University of Nevada, Reno Extension

- Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

- College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources

- Department of Agriculture, Veterinary & Rangeland Sciences

- University of Nevada, Reno Experiment Station

- Experiment Station Main Station Field Lab

- Molecular Biosciences Graduate Program