In this first-person narrative, Drew Haebler, undergraduate researcher at the University of Nevada, Reno, tells Nevada Today about his experience investigating how veterinary medical education prepares clinicians to address public health challenges through a One Health lens.

Growing up with two veterinarians as parents, I often heard about zoonotic diseases – infections such as rabies and salmonella, which are infections that can pass between humans and animals. My interest in this topic deepened upon hearing about the outbreak of avian influenza, a viral zoonotic disease capable of moving between wild and domesticated birds and animals, and even humans. After watching how quickly the virus was spreading between wild and domesticated birds, and hearing reports about the first human cases, I became fascinated with learning more about the relationship between humans and animals, and the environment that we all share.

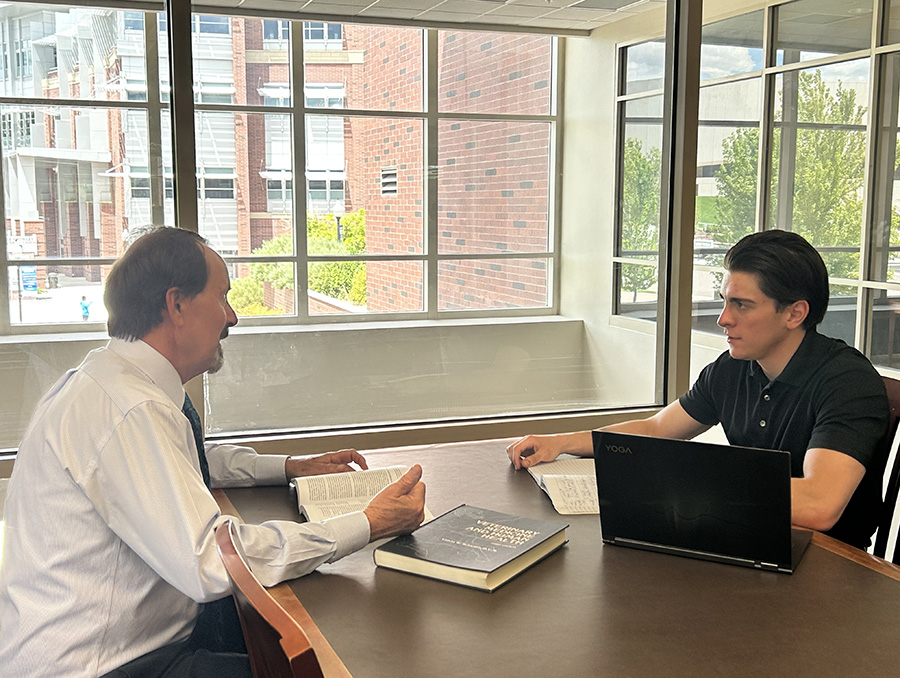

This curiosity led me to reach out to Dr. Benjamin Weigler, DVM, MPH, Ph.D., DACLAM, DACVPM, a nationally recognized zoonotic disease epidemiologist and research animal veterinarian, who introduced me to the concept of One Health. He explained to me that this was a holistic approach to medicine that, according to the CDC, “recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment.” This discussion gave a name to the curiosities I had, but it also began to raise new ones. Dr. Weigler and I began to wonder: How are veterinary schools teaching veterinarians about One Health?

Dr. Weigler explained how veterinary schools across the country are working to integrate One Health into their curricula. Veterinarians are not only responsible for treating sick pets, zoo animals and livestock, but are also responsible for preventing and managing zoonotic diseases, monitoring human and animal food sources, and advocating for environmental safety. Veterinarians are critical public health safety proponents.

Clinicians – whether physicians or veterinarians – are far more than individualized healthcare providers. They are at the forefront of public health safety, playing a critical role in disease prevention and community well-being. As we began to think about veterinary medical education and its connection to human health, we asked the question: Are medical and nursing students in Nevada learning about One Health at the same level as veterinary students?

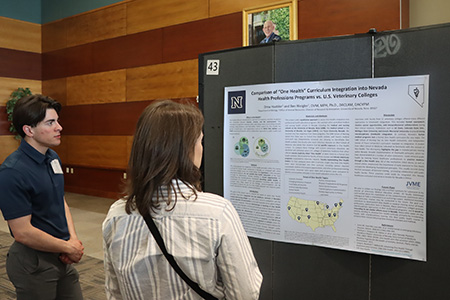

I had the opportunity to work alongside Dr. Weigler to assess the integration of One Health principles within the course curricula for human health professions in Nevada, as compared to the bulk of veterinary colleges across the United States. Over the spring 2025 semester, Dr. Weigler and I conducted interviews with faculty from 10 U.S. veterinary programs and one international veterinary program, all of which were known for embedding One Health into their educational programs for veterinary medical students. These institutions included the University of California, Davis, the University of Arizona, Colorado State University, Texas Tech University, the University of Minnesota, Michigan State University, Lincoln Memorial University, North Carolina State University, Cornell University and Tufts University. Our structured interviews with more veterinary colleges are continuing through the summer 2025 term.

To assess how One Health is addressed in human healthcare curricula, we reached out to the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, the University School of Nursing, UNLV School of Medicine, and Touro University Nevada College of Osteopathic Medicine, to ask about One Health integration within their respective curriculum. We only heard back from the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine and the University's nursing school. Upon speaking with infectious disease faculty from the School of Medicine, we learned that there was no formal One Health integration. The nursing school also confirmed no formal One Health content. To gather additional insight, I spoke with a colleague enrolled in UNLV’s School of Medicine, and they had no knowledge of One Health, confirming that UNLV also did not teach any formal One Health content.

Other institutions, namely UC Davis, Colorado State University, Michigan State University, and Lincoln Memorial University, stood out in the ways they integrated One Health within their curricula. These programs promoted interprofessional collaboration between medical, veterinary and public health students. This stark contrast highlights the gap in interdisciplinary training in Nevada, where human healthcare programs lack a formal One Health education. Broader implementation of One Health principles, like those seen at other institutions, could strengthen public health education in Nevada by helping healthcare professionals approach medicine from a broader, more interconnected perspective to solve common problems.

We are continuing to interview U.S. veterinary colleges to assess how they are integrating One Health within their school-specific curricula so that we will have captured this information from nearly all of them. We plan to submit our findings to the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education for publication in conjunction with a professor at Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, alongside other colleagues across the country. The faculty we interviewed are very pleased to hear about this project and excited to read our forthcoming results. We also already have a manuscript accepted for a separate project to be published in the Kansas State University One Health Newsletter, where we discussed the impact of international collaboration between American and Eastern African veterinary students.

For any other undergraduate students who are looking to get involved in research, I would suggest that you are always open to change. This project has evolved so much over the past six months, and every turn has brought along new opportunities that I would have never expected.

Learn more about how to get involved with research as an undergraduate student.

About the author: Drew Haebler is an undergraduate researcher set to graduate in December 2025 with a degree in biology. After graduation, Haebler plans to complete a graduate certificate in One Health before attending veterinary school.