As the conversion to electric vehicles and generation of power from sustainable sources quickly gains momentum, research teams based at the University of Nevada, Reno wrestle with the challenging questions raised by the conversion to a new energy future.

They’re addressing the need to manage millions of used batteries and the challenges of using scarce and expensive materials to build new batteries. They’re looking for improved battery technologies that would allow motorists to travel farther with fewer and shorter stops for recharging. They’re examining ways to improve storage of electricity at power plants that rely on sustainable sources of energy. And they’re helping prepare a diverse set of students for the corresponding, new workplace opportunities.

A diverse group of researchers is working together on those issues through the Nevada Institute for Sustainability, a virtual organization at the University and part of the College of Engineering. The Institute brings together faculty from the University, along with researchers from U.S. Department of Energy National Laboratories, non-profits, and private industry.

The Institute has collaborative agreements, too, with researchers at schools that include two-year and tribal colleges, historically black colleges and universities and institutions that serve Hispanic populations.

There’s no shortage of important research to be undertaken, says Dev Chidambaram, a Professor of Chemical & Materials Engineering who serves as director of the Institute. For example, research pertaining to questions raised by the millions of used batteries that will result from the conversion to electric vehicles.

Recycling battery materials is the option that’s getting a lot of attention.

“This way, we reduce the use and demand for virgin material, which makes this process even more sustainable and green,” Chidambaram said.

Currently, however, less than 5 percent of lithium-ion batteries are recycled in the United States, compared with about 99 percent of the lead-acid batteries in widespread use.

Recycling of used lithium-ion batteries, which currently relies on melting them down, would be far more efficient with a low-temperature process. Institute researchers are looking for answers as part of a wide-ranging effort to develop commercial recycling technologies that can accept lithium-ion batteries universally.

But instead of recycling, what if used vehicle batteries could be repurposed and used at renewable energy plants, which don’t need the same levels of performance as a car or truck? Or maybe batteries could be rejuvenated just as auto parts are remanufactured today.

“Why break down the entire battery and build it again if we can rejuvenate the degraded components and put the battery back together again,” Chidambaram said.

As those questions swirl around, the mantra of the Institute these days has become “Reuse, Rejuvenation and Recycle” — sometimes simply shorted to “Batt-Re3.”

At the same time, Institute researchers search for technologies that allow battery manufacturers to pack more storage into batteries without increasing their size, allowing longer trips between stops for charging. Other research seeks methods to deliver faster and safer recharging. And important research continues to focus on improved battery performance at very low temperatures, where today’s lithium-ion batteries don’t function well.

Other ongoing research concentrates on battery storage at sustainable-energy plants, such as those that rely on wind or solar power to generate electricity. Those facilities need lots of energy storage so they can deliver electricity even when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing, but batteries at those facilities don’t require the same lightweight, expensive materials that are at the heart of vehicle batteries.

For those stationary applications, Chidambaram says his research group is developing a high-performance, high-safety, grid-sized, low-cost battery that relies on liquid metals, with specific focus on waste byproducts and low-cost earth-abundant materials.

While significant federal and state research grants have been awarded to the Institute, private industry is funding the work on grid-scale liquid-metal batteries. With a large and growing complex of battery-storage companies in northern Nevada, the Institute works with companies involved in lithium mining, battery production and battery recycling.

“I can confidently say that we are working with almost all the companies in the lithium and battery space in the region,” Chidambaram said.

Growth of the lithium and battery sectors as keystones of the northern Nevada economy requires the trained and capable workforce that’s being created in the Batteries and Energy Storage Technologies Minor that Chidambaram created at the University.

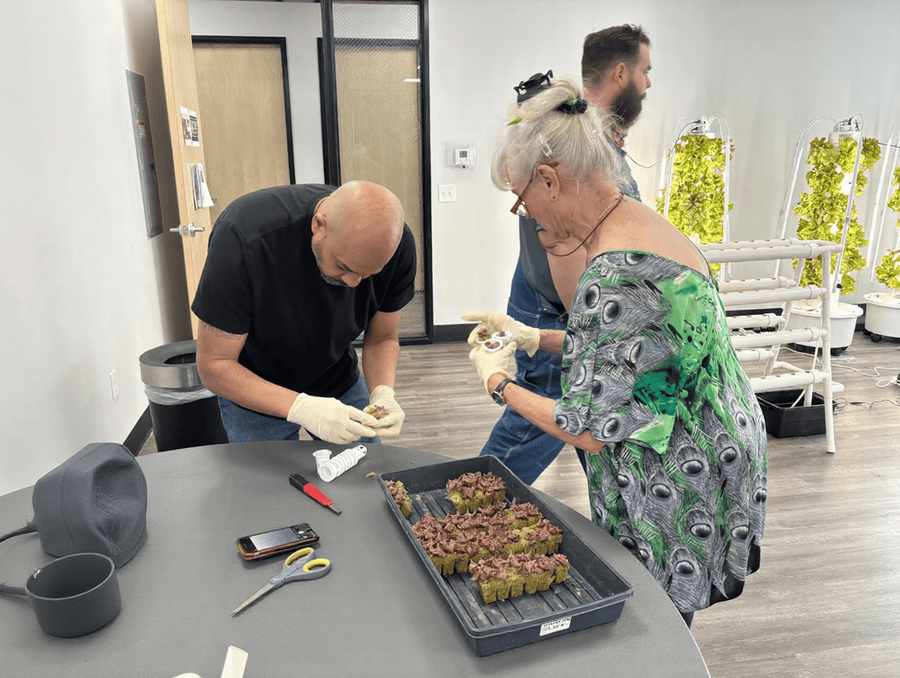

Centerpiece of the minor, the first of its type in the United States, is a hands-on laboratory in which students make and test their own lithium-ion batteries, starting with raw chemicals.

“Many of the students who have graduated have gone to be employed in the battery industry, primarily in northern Nevada,” Chidambaram said.

Today, they hold positions ranging from engineers to chief technology officers.

Opportunities for those graduates as well as demand for the research underway through the Nevada Institute for Sustainability will only increase as the world seeks to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels.

“We are in a great place regarding battery technology, and significant innovations will happen in this space in the next decade,” Chidambaram said. “We in northern Nevada will be part of the force driving that change.”