Research recently published by faculty at the University of Nevada, Reno explored how head impacts that don’t meet the criteria for concussions may still harm the brain. The study was led by Nicholas Murray, an associate professor in the School of Public Health and director of the Neuromechanics Laboratory. Murray was curious how slow eye movements, called smooth pursuits, would be affected by repetitive head impacts. He collaborated with Marian Berryhill, a cognitive neuroscientist and professor in the College of Science’s Department of Psychology, and they recently published their findings in JAMA Ophthalmology.

It's normal for eyes to move about three times per second. When you’re moving your eyes, you can’t see, but because it happens fast, you don’t generally notice it. A key aspect of athletics is knowing where to look next, which is related to smooth pursuit velocity.

“Talented athletes have superior eye movements and ability to look ahead, especially for sports like football where the athletes have trained on a specific drill and can anticipate what will happen next,” Murray said.

Murray specifically wanted to investigate repeated head impacts, a technical term for impacts that do not meet the clinical threshold for a concussion. He collaborated with Berryhill, whose research area includes studying eye movement, because postural stability and eye movement are the two most sensitive measures of potential injury to the brain after a head impact.

While athletes practice anticipatory eye movements all the time and are particularly talented at it, eye movements are also associated with maintaining attention and ignoring distraction. These are important skills for cognitive tasks, like doing homework or reading a book.

The Neuromechanics Laboratory provides concussion testing for the University’s and Truckee Meadows Community College’s athletics programs, Washoe County School District and more. The lab conducts diagnostic testing for athletes who have taken hits in their sports and provide pre-season recommendations for clearance. The relationship between the Neuromechanics Laboratory and the athletic departments at the University provided an important opportunity for Murray to collect data to answer his questions.

“Longitudinal projects of this scope take years to develop the appropriate level of trust to complete the study aims,” Murray said. “Our research group has spent many years developing a mutually beneficial relationship built on trust with our athletes, athletic trainers, and team physicians. This study required all the parties working together to help us achieve this important study.”

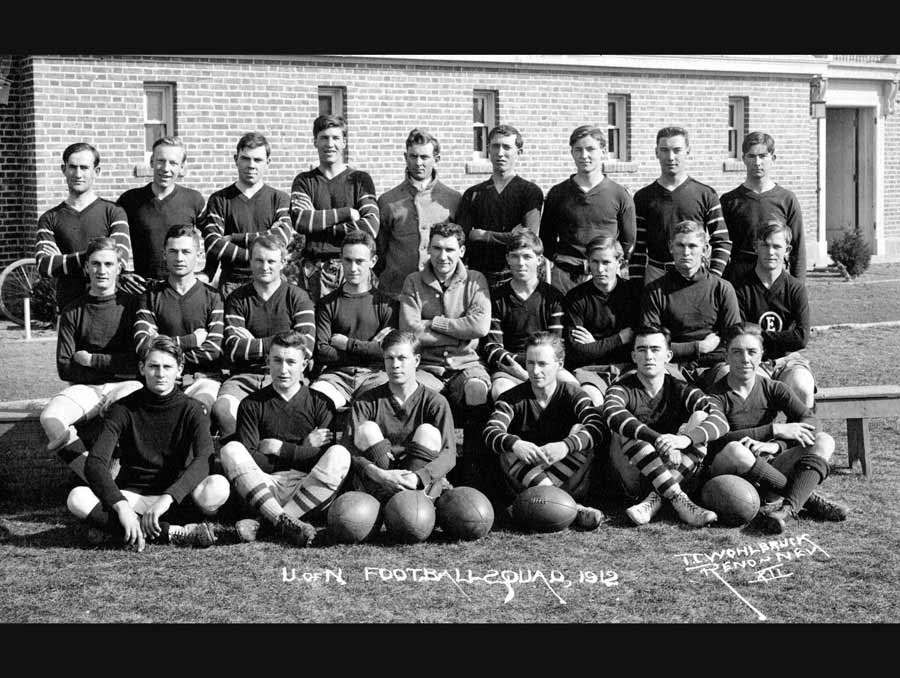

The study compared eye-tracking at the beginning of the season for athletes in a contact sport (football) and in a non-contact sport (swimming) to their eye-tracking again at the end of the season. Football players were divided into high-dose groups and low-dose groups depending on how many hits they were expected to take depending on the position they played. Repeated head impacts were recorded with custom mouth guards the athletes had to wear for a season. Over time, some of the study participants were excluded from the study’s analysis, because they were no longer playing, in some cases due to injury, or because they took their mouth guards out too often.

The study showed there were no significant differences between the non-contact athletes and the low- and high-dose football players in their smooth pursuit eye movements at the end of the season, though the high-dose athletes did experience a decline. The scientists said this isn’t surprising, partially because the low- and high-dose athletes are constantly working on improving their smooth pursuit velocity by drilling football plays.

“Despite the fact that they probably have more exposure to that training, they’re still seeing a decline by the end of the season,” Berryhill said.

The researchers hope to expand the research to get a larger sample size and perhaps follow athletes through multiple seasons. The effects of receiving an impact can vary heavily based on all sorts of variables, like neck strength, neck height, torsion, age, hormones and more. With the current available data, coming up with a standard rule for what happens after a player takes a hit is impossible.

“You need oceans of data to make those little simple rules,” Berryhill said. “And so, it's contingent upon access, funding, time and having a good array of players in different sports.”

What does this all mean? Murray said that maybe worried parents of football players can relax a bit.

“Hitting your head is bad, but we're also not eggshells,” Berryhill added.

In the long term, Murray hopes to develop a model for understanding what impacts athletes can withstand without injury, obvious or not.

“Then, take that model and move it out of the college space and go down to pop warner, go down to high school, go to the actual largest stakeholder population for contact sports in the world,” he said.

Berryhill became interested in studying head injuries and eye movements when she found out about Murray’s work and desire to better design diagnostics for head injuries. Both have felt that the collaboration in this research has made them better scientists.

“Nick is amazing at getting, longstanding relationships and funding to keep the wheels turning,” Berryhill said. “And right now, that's really hard to come by.”

Those longstanding relationships are what made the research possible in the first place. Repeated head impacts are difficult to research because, unlike with concussion studies, there isn’t any reason for athletes to be evaluated outside the study, so access to athletes is difficult to obtain.

Murray’s research and mentorship of students has led to significant changes in concussion policies for K-12 students in Nevada. In 2023, a bill authored by Stella Thornton, a student researcher working with Murray in the Neuromechanics Laboratory, was signed into law. The bill, inspired by Thornton’s own experience with concussions, updates concussion management guidelines with new policies for students re-entering sports and learning environments. Murray’s research is all about ensuring that student athletes don’t have to compromise one part of their title for another.

“Our study is just scratching the surface,” Murray said, “We’re trying to get at the answer not to stop sports, I love sports, but to make sure they happen safely.”