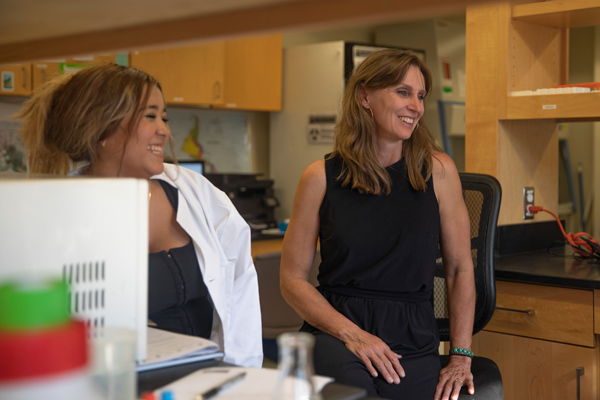

Associate Professor and recently named Trevor J. McMinn Research Professor of Biology Jamie Voyles has traveled the world to study diseases in wild animals.

“It was an incredible honor to receive the McMinn Professorship,” Voyles said. “It's important to continue to recognize women in science and to recognize science that may not be in the University’s backyard, but is doing important work from a global perspective. The McMinn Professorship, to me, means an opportunity to have a wider audience to talk with about some of these really big and important issues.”

Voyles has studied bat white nose syndrome and diseases impacting snails, but her primary focus for the past 20 years has been amphibians (frogs, toads and salamanders).

A journey to save the frogs

Voyles was a graduate student learning about amphibians in the tropics when infectious disease outbreaks began impacting frogs in places like Panama. In 2004, when Voyles was a graduate student, her advisors recommended she change research paths because of the catastrophic declines in frog populations due to disease. She and her colleagues spent months at a time in the jungles of Panama searching for the frogs for almost a decade. They nearly lost hope.

“I didn’t have a huge background in infectious disease,” Voyles said. “But once that happened in the tropical rainforest streams of Panama, that’s when I got really interested. And the more I got into disease ecology, the more I loved it and never looked back.”

Voyles studies how the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) causes chytridiomycosis, a skin disease, in frogs and what its impacts are. Bd is known to have caused amphibian declines and likely extinctions around the world. In 2009, while Voyles was pursuing her Ph.D. at James Cook University in Australia, she and several colleagues, including her father, published a paper in Science about how Bd kills frogs. More than a decade later, the disease is still wreaking havoc on amphibian populations.

“It’s the most devastating infectious disease of vertebrates that we have ever seen,” Voyles said.

That includes the Black Plague, which wiped out a third of Europe’s human population in about five years. While the origin of “chytrid fungus,” another name for Bd, isn’t known for certain, it likely originated in Asia where amphibians seem to have immunity to chytridiomycosis. The pathogen spread to other continents due to human activity and the pet trade, which causes disease spread in many different types of animals.

As Voyles searched for frogs in the field, she was seeing fewer and fewer of the amphibians, and the outlook for many species was grim. However, in 2012, Voyles and her colleague found a living frog that had been assumed extinct: the Panamanian Golden Frog, the national animal of Panama. Nobody had seen that species in years, and the finding gave the researchers a great deal of hope. Some species, like the Golden Frog, may be developing resistance to Bd, and Voyles and her colleagues are working on determining how they do it.

“We have documented recoveries in some species, a small subset in Panama, even though the pathogen is still present and still lethal to many other species,” Voyles said. “What that tells us is that there's been a shift in the disease dynamics.”

To study those shifting dynamics, Voyles and her colleagues founded RIBBiTR, the Resilience Institute Bridging Biological Training and Research, to train younger scientists in studying infectious disease in amphibians. The institute is meant to be interdisciplinary.

“We want people who are interested in microbiology to feel equally comfortable talking about ecosystem-level ecology,” Voyles said. “The goal for all of our trainings is to build vocabulary, fluency and competence in multiple different areas of biology.”

RIBBiTR also provides outreach and education to local communities, helping to spread awareness of the crisis facing the world’s beloved frogs.

Voyles’s commitment to making science accessible

One of Voyles’s priorities as a scientist is helping to make science more accessible to diverse groups of people. She has served on multiple committees centered on DEI initiatives and has made a commitment to serve underrepresented people in science in her own lab.

Voyles received National Science Foundation (NSF) funding to form STEM Sisters, a program that brings high school students from underrepresented backgrounds into her lab. The first year, Voyles had a 6-week training program. Voyles could only afford to do the program for a year, but several donors learned about the project and wanted to provide those opportunities to more students. Because of their generosity, Voyles was able to continue the program for a second year. Two of the students returned to serve as mentors to the next cohort of STEM Sisters, and each of the mentors plans to continue their education.

“Having diverse perspectives and diverse identities involved in scientific research is really important,” Voyles said.

The remote rainforest field sites where Voyles works in Panama aren’t the ideal place for plans to fall through, but it happens. Voyles said that diversity can help immensely in problem solving to address those issues.

“If that involves language skills or that involves different lived experiences in the past or coming from different communities, all of that feeds into the improved ability to address particular challenges when they arise,” she said.

An impressive career

Voyles has won numerous awards as a faculty member at the University, where she has been working since 2015, including the Dr. Donald Mousel and Dr. William Feltner Annual Award for Excellence in Research and the Hyung K. Shin Award for Excellence in Research. She has received funding from organizations including the NSF, the U.S. National Park System, the National Institutes of Health, and National Geographic, among others. She is a recipient of an NSF CAREER Award, and last year, Voyles was awarded the NSHE Regents’ Mid-Career Research Award.

Most recently, Voyles has been named a Trevor J. McMinn Research Professor of Biology. The endowment will support students through several phases of education, from high school, to undergraduate, to graduate school. For Voyles, it means that she will have the opportunity to be a role model to the next generation of scientists, just as her parents are to her.

Voyles has been passionate about science for a long time and said that her parents have fostered that passion since she was young. Her mother took her to Florida to see the first female astronaut launch into space, and her parents helped her submit scholarships so she could go to space camp. They let her dig up the backyard in search of dinosaur bones and encouraged her to pursue science. Voyles’s father, who is a scientist, was a coauthor on the Bd research paper with Voyles.

“They did a lot of things that made me feel like science was a valuable and important thing to do with my time as a student and then ultimately as a career,” Voyles said. "My parents were my main cheerleaders when I was young, and I want to be a cheerleader for students like the STEM Sisters."

The STEM Sisters have an opportunity to showcase the research they’ve done with their cheerleader through a symposium on April 19.