While much of the cat and dog food tested in a years-long study had concentrations of mercury that are high for chronic consumption, according to a new study published in the Elsevier journal Science of the Total Environment, the majority of the pet foods tested had mercury concentrations below suggested levels. The study also discovered a high number of inaccuracies in labeling of ingredients, indicating a need for an established and enforced limit for contaminants in pet foods based on what is safe for chronic consumption, as well as policy and regulation to ensure accurate ingredient labeling in pet foods.

"Only two of our tested samples had mercury concentrations above the maximum tolerable levels recommended by the National Research Council," Sarrah Dunham-Cheatham, assistant research professor at the University of Nevada, Reno and lead author of the paper, said. "The next two highest were dry dog foods from a pet food company that is currently under lawsuit for their high toxic metal concentrations. The top 10 highest foods we tested included six cat foods (three wet, three dry) and four dog foods (all dry)."

Based on the package ingredient labels, tuna was listed as the first ingredient for both products, with other seafood-based ingredients, such as salmon or crab, listed as top ingredients, though no single ingredient is the main source of mercury in commercial pet foods, according to the study that tested 59 dog foods (both wet and dry), 14 dog treats, 17 dry cat foods and 35 wet cat foods.

The authors noted that without an established and enforced limit for contaminants such as mercury and methylmercury in pet food products, the pet food industry may continue to make and sell products that pose risks to pets. They also noted that additional studies to establish safe consumption levels of mercury in pet species are needed to determine the safety of pet food products for chronic consumption.

"There are no regulatory standards for mercury in pet foods, but there are several suggested limits from various sources," Dunham-Cheatham, based in the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources, said. "For this paper, we selected a limit suggested by the National Research Council, as it is in the middle of the range of suggested limits and is the most commonly referenced limit in pet food-related literature."

"Based on our results, I would encourage pet owners to avoid or minimize the feeding of fish-based foods to their pets to mitigate potential risks related to chronic mercury exposure," Dunham-Cheatham said. "If a pet is a picky eater and prefers fish-based foods, try rotating it or mixing it with a nonfish-based food. If a pet has a food allergy, talk with your veterinarian about which food they recommend feeding the pet to ensure the pet is not at risk of accidental exposure due to adulteration (the inclusion of an ingredient in the product that is not included in the package ingredient list, and/or the exclusion of an ingredient in the product that is included in the package ingredient list)."

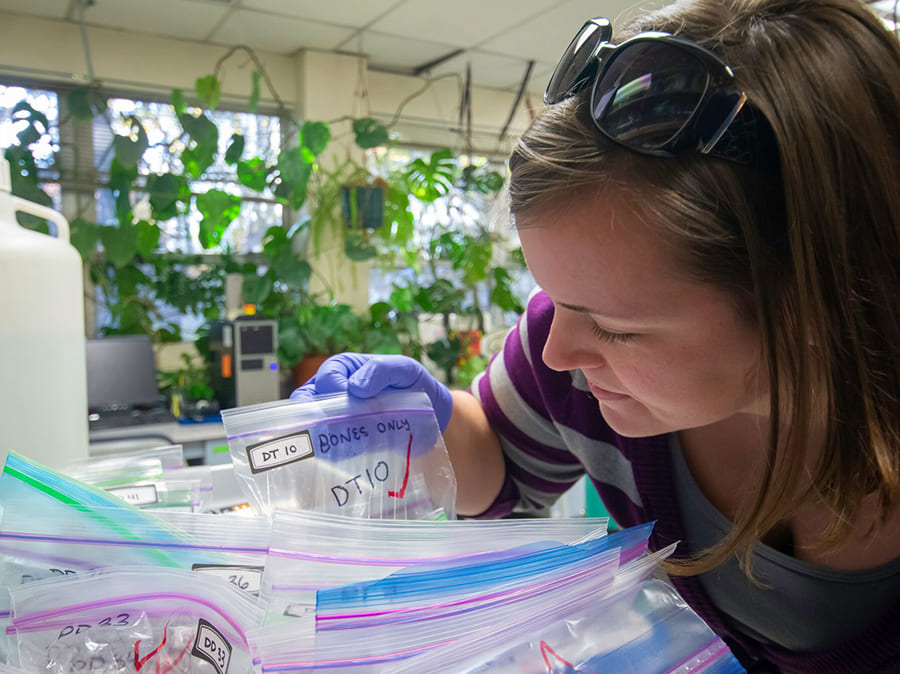

The researchers used DNA in the pet food to test whether actual ingredients matched package labels and suggest that pet food package labeling should be read with caution, as many ingredient labels are not accurate.

"Every sample we looked at had some inaccuracy, based on our results, some more egregious than others. These are highlighted in the paper," Dunham-Cheatham said. "We looked at at least 50 samples, of the 90 we analyzed for DNA, for this particular analysis. We weren't able to definitively answer how many had inaccurate labels due to some limitations of the DNA analysis. As for the DNA results, generically speaking, we found that many of the pet food products were comprised of low-value ingredients, such as chicken, and that products claiming to be made from high-value ingredients, such as fish and novelty proteins, typically contained more low-value ingredients than high-value ingredients."

The study, published in February in Science of the Total Environment, was authored by Dunham-Cheatham and her colleagues Kelly Klingler, Margarita Estrada and Mae Gustin.

After mercury was found in pet food in a 2016 research project at the University of Nevada, Reno, this new team took a closer look.

“As scientists at the University of Nevada, Reno and experts in the fields of mercury and genetic analyses, we want to learn more about what is really in pet foods and help consumers make a more informed decision when purchasing food for their pets,” Dunham-Cheatham said.

“We as humans often are exposed to unknown contaminants in our food; animals are even more susceptible to contaminants in food because they are fed the same food daily,” Mae Gustin, professor in the Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences, who primarily conducts research on mercury in the environment, said. “It is important for people to know that the foods they are feeding their animals are safe. This information is important for manufacturers of pet food as well as for pet owners.”