Millions of acres of forest, grassland and rural communities in the American West were destroyed, and many people killed, by wildfire in 2017. In Nevada alone, over a million acres of wildland was burned over in one of the Silver states most active years. Despite these numbers, people, communities and millions of more acres are still under threat by wildfire today.

State-of-the-art mountaintop cameras from the University of Nevada, Reno, a new and expanding tool for fire mangers who oversee the wildland and wildland/urban interface, spotted or tracked 240 fires in Nevada and California in 2017, helping to keep firefighters more situationally aware and able to mount appropriate responses more rapidly over tens of thousands of square miles of forests and rangelands, including rural communities.

“The success of our system lies in our ability to deploy wireless, microwave technology to enable high-speed Internet out in the wilderness,” Graham Kent, director of the Seismo Lab in the College of Science, said. “We call it the Internet of ‘Wild’ Things or wilderness Internet.”

The high-definition near-infrared night capable fire cameras are part of the Alert Wildfire network, conceived, developed and implemented at the Nevada Seismological Lab. The network has grown from the AlertTahoe system that began with a three-camera pilot project at Lake Tahoe in 2015 to four networks with over 55 cameras covering areas of Nevada and California, including San Diego County and Santa Barbara, with an eye to Oregon and Idaho coming online soon, with several more states making inquiries.

Fire monitoring marries Seismic monitoring

The Nevada Seismological Laboratory monitors earthquake activity in Nevada and eastern California with a system of 200-plus seismometers connected via private high-speed internet communications, providing earthquake data to emergency managers at USGS and other public agencies. It was this communications network that supported the nascent camera network at Lake Tahoe in its early years. Today, the expanding network grows primarily through pressures to expand fire coverage, which in turns, helps make a more expanded and resilient network for earthquake monitoring.

The concept at Tahoe soon mushroomed into the Great Basin of Nevada, with the Bureau of Land Management in Nevada investing in a dozen cameras strategically located to protect natural resources and rural communities. The system proved its value as cameras captured the HotPot fire. The system helped fire managers get a rapid deployment of resources by being able to show the explosive nature of the HotPot exploding at a pace of 10,000 acres an hour across the high desert grass and brush land, burning 100,000 acres in about one day. The cameras helped firefighters to save the small town of Midas, Nevada, which was in the path of the massive wildfire.

“Whenever we get a report of a fire, we’re able to turn the camera to whatever that location is, confirm it and if the fire’s higher than what the response level dictates for that day, we can also adjust that response level from our dispatch centers,” Paul Petersen, BLM Nevada director of fire operations, said. “This camera network gives fire managers a real-time picture of what is happening from both a weather and fire behavior standpoint.”

While the concept is that the system can spot the fires when they first ignite – before they get out of control – the cameras aren’t always the means of first report. But after someone calls in a report of smoke, fire managers can immediately turn the cameras to the direction of the reported fire and have eyes on the fire to assess the situation and determine what resources are needed. While they may deploy spotter planes to assess the situation as well, they don’t have to wait for the plane, or someone on land, to get an overview of the fire scenario.

Mac Heller, manager of the dispatch center used by several agencies in the Lake Tahoe Basin, the U.S. Forest Service’s El Dorado Incident Command Center in Camino, California, said the cameras help him determine the type of response to send to a fire. Heller and his crew use the cameras daily.

“If the cameras only show a little fire activity, we'll send a smaller response,” he said. "If a fire is actually taking off, moving very quickly, then we can increase the response as well. We'll know in 20-30 seconds and that is the beauty of it.”

In 2017, the AlertTahoe/AlertWildfire system (with 38 cameras) was involved in a staggering 207 fires in northern Nevada and the eastern California side of the Sierra Nevada. In southern California, one solo camera near Santa Barbara played a critical role on three fires, including the Whittier Fire and Thomas Fire during its approach into Montecito. The Santa Ynez camera was spearheaded by Frank Vernon at UC San Diego and Jamie Steidl from UC Santa Barbara. The AlertSDGE system with 16 cameras, which went into operation in October 2017, was involved in 30-plus fires (with nearly half on the Mexico side of the border), including the Lilac Fire where a camera atop Red Mountain and Palomar Ridge followed the fire from 35 seconds after the 911 call to its ultimate containment.

While the system has already successfully assisted with early detection of wildfires, it also played a critical role for early detection during an arson outbreak in late 2016 at South Lake Tahoe with some 30 fires in a 60-day period both in the City of South Lake Tahoe and th

Artificial Intelligence

In fall 2016, the fast-moving Emerald Fire near South Lake Tahoe started at 1:16 a.m. Though no one was watching, the cameras picked up the first signs of the fire 14 minutes before the first 911 call came in, highlighting the need for an auto-detect capability that will alert fire managers.

In 2017, Kent brought another partner into the system, IT for Nature from Poland, providing machine vision auto-detect and learning – software that can detect the first signs of smoke – which has been successful where implemented.

“The cameras have to be monitored for them to be most effective,” Kent said. “The on-demand time-lapse video we produce is a useful first step, but we’re excited for the auto-detect software to capture critical intel even earlier,” Kent said. “On the Emerald Fire video from 2016 at Lake Tahoe you can also see a smaller arson fire break out in the foreground one hour, 45 minutes later. Crews were able to get a jump on that secondary fire and put it out before it caused any damage to nearby homes, and the camera played a critical role.”

“Lake Tahoe’s fire chiefs have been briefed on the program and are impressed with what they learned,” Mike Brown, chief of the North Lake Tahoe Fire Protection District, said. “What they have to offer is awesome when it comes to early detection.”

“Basically, 911 cell phone calls typically beat machine vision this past year, but not by much, so we anticipate in the next couple years the machine will get faster,” Kent said. “Plus, we’ll build outreach programs to crowdsource the cameras, which will likely always be the fastest. It’s really an all-in approach to get on top of fires early on.”

“But right now we need to balance those efforts with building out more cameras because the greatest benefit so far is to know exactly how to scale resources up or down after the first glimpse of fire or smoke. This will always be the greatest asset of the system. But over time, we anticipate that many fires will be first detected by ‘machine’ and not humans.”

Multi-Hazard Approach

The University of Nevada, Reno is in a lead position nationwide in developing the inexpensive, multi-use, high-throughput, emergency-grade internet protocol networks and expanding their use for all-hazard monitoring.

The AlertWildfire networks use and augments the Seismo Lab’s earthquake monitoring network that crisscrosses the third most seismically active state in the nation, turning the seismograph recording sites into hazard monitoring networks able to track fires, floods, hazardous weather such as ArkStorms and landslides. The Seismo Lab, working with the University of Oregon, installed two cameras in Washington State to monitor a potential landslide area and is working with California State Parks to help them deliver two cameras at the Oroville Dam in California to monitor work and environment of the dam’s damaged spillway and catch large fires such as the Wall and Ponderosa fires this past year

“With our private, high-speed internet communications network in place, these sites also easily adapt to earthquake early warning detection systems that can provide public notification of expected, potentially damaging ground shaking,” Kent said. “The system could be the backbone for a more resilient earthquake early warning system as the current ShakeAlert buildout is heavily leveraged on cellular technology.”

On Donner Summit in the rugged Sierra Nevada of northern California, Sugar Bowl Ski Resort experiences some the highest winds – 180 miles per hour – and the deepest snows – 60 feet of snowfall – and temperature fluctuations that can originate one week in Hawaii or the next week in Alaska.

“We have partnered with our Nevada Climate Office to build out the multi-hazard concept with extreme-weather recording at Sugar Bowl,” Kent said. “It’s a three-camera system now top to bottom with state-of-the-art weather recording gauges and even an early earthquake warning station down low.”

“The multi-hazard approach actually helps us to build the best seismic network in the U.S.,” Kent said, “as we tend to build in a lot of resilience for the fire cameras because you know you’ll have fires all the time so the network better work each and every day – all day and all night. So ironically, expansion into fire has made us a very big player in the seismic arena.”

“The AlertWildfire networks epitomize our goal for community outreach,” Jeff Thompson, dean of the College of Science, said. “The Seismological Lab is inherently service to community, providing alerts to the public, government agencies and emergency managers. The addition of the AlertWildfire systems is a natural evolution of what our group is all about. Graham and his team have worked hard to make this happen, and it’s no wonder they’ve been successful.”

Crowdsourcing

While the camera system is designed for the fire managers to spot and track fires, with the ability to zoom, rotate 360 degrees and tilt on several cameras at once, it is also public-facing, with the camera views available for the public to monitor 24/7.

The system allows dispatchers and duty officers at fire command centers to play back the camera feed to detect anomalies and gather a local picture of what is happening, and has happened, within the field of view of the camera. More than 150 firefighting personnel have access to these fire cameras in their arsenal to fight fires; users range from USFS, BLM, Cal Fire and local fire protection districts.

“Our fire cameras are controlled from Incident Command Centers such as Camino, California near Placerville, or the Sierra Front (near Minden, Nevada),” Kent said. “Many local fire protection districts also have access to the same cameras.”

Fire managers can manually rotate, tilt, pan and zoom the camera. While fire agencies can move the cameras with this active pan-tilt-zoom functionality, the public can observe the real-time views, as well as the time-lapse functions with a 15-minute, 60-minute, 3-hour and 6-hour time-lapse utility built into the webpage viewer (right-click on the camera image for options). The Seismological Lab’s YouTube channel, nvseismolab has a library of videos captured from the network.

“What is also true, crowdsourcing, if appropriately implemented, will likely beat out the “machines” every time,” Kent said. “We envision an army of volunteers on the cameras over time, especially times where fire danger is grave, and that will likely be the fastest path to discovery, with machine vision as a viable back up.”

Crowdsourcing is essentially fire lookout towers with thousands of people looking out through the forests, high-mountain deserts, rangelands, sagebrush and rural communities for puffs of smoke rising above the horizon.

San Diego Fire-Rescue Chief Brian Fennessy said that during the ignition of the Church Fire in southern California, “I could watch the smoke on my iPhone, the color, the direction, and immediately knew the resources that I needed to deploy and the time they would be engaged. Furthermore, the crews could watch how the fire progressed on their iPads as they approached the fire, real-time situational awareness – these fire cameras are a game changer.”

The Network Infrastructure

The technology mixes new and old approaches. Lonely fire spotters used to sit in towers on remote mountain tops with binoculars looking for smoke, now the cameras sit on mountaintops with a promise of better coverage. They aren’t replacing the fire spotters, they are augmenting the system being deployed over many mountaintops in a region. Using existing radio communication towers, the Nevada Seismo crew installs the line-of-sight system, including the HD cameras, and microwave communications equipment.

“The advantage of having our own Internet system is that we have high-speed broadband in places there isn't any cellular coverage,” David Slater, senior systems analyst for the earthquake monitoring and Alert Wildfire networks, said. “Cellular coverage has limited bandwidth. Video requires lots of bits to run and with a 1080P camera we can blow through a cell plan amount in a couple of days. Even with cell service, we still couldn’t run our network to its full potential.”

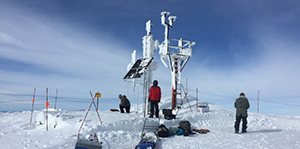

The Seismo Lab crew travels extensively to the middle of nowhere. They cross ancient lakebeds, climb to 11,000-foot peaks and bounce through snowdrifts to get to the mountain tops with their pick-up truck loaded with tools and the components for the system. They even had a local Rotary service club help Sherpa equipment to a remote location where vehicles couldn’t access the site.

“It can be very challenging accessing these remote sites and not all of them can be accessed with our trucks,” John Torrisi, associate engineer, said. “We also have sites planned for this year that will be helicopter access only. Jacks Peak north of Elko is extremely difficult even in the summer. At 11,000 feet elevation, ‘summer’ is a very small window and since the access is so steep, we can't use vehicles. That's just one of many difficult sites. Basically they're all in very remote areas and difficult to access.”

The Seismo Lab designs and installs the entire system, including the camera, antennas, solar/battery power systems and enclosures containing all the networking/control equipment to make it work as a complete system. Some sites they install the tower itself and do all the concrete construction.

Funding and Collaboration

“As a mostly soft money organization, without proper funding from the feds or the state (though that might change), we have to get inventive to keep a talented staff around,” Kent said. “So cash is king for the fire cameras and other sensor network projects. That said, this multi-hazard approach actually helps us to build the best seismic network in the U.S., as we tend to build in a lot of resilience for the fire cameras because you know you’ll have fires all the time so it better work each and every day.”

Through partnerships, collaborations and outreach with fire agencies, landowners and community organizations to fund acquisition and installation of mountaintop high-definition camera systems, the University of Nevada, Reno has made great inroads to helping many agencies with fire response. They work with the BLM, U.S. Forest Service, Cal Fire, Nevada Division of Forestry, a dozen local fire protection districts as well as other agencies such as NOAA weather service, air pollution control districts, to name a few. Fundraising also comes from the public where the Tahoe Prosperity Center helped land seven cameras in and around the Tahoe basin as they spearheaded these critical efforts.

“The first order of improvement comes with camera expansion,” Kent said “No other expenditure can compete in terms of impact other than just adding more cameras. There will likely be benefits by improvements in 4K camera technology (HD imagery is still better right now). The system quickly pays for itself based on the cost of operational savings, property destruction and forest management. It also provides huge benefits for other hazards, earthquakes, and atmospheric rivers. It’s a very organic system with many agencies to universities to business interests all involved.”

The University’s watchful mountain-eye concept has most recently been applied to the new system in San Diego County with the lab’s partners Neal Driscoll and Frank Vernon at University of California, San Diego funded through San Diego Gas and Electric. The San Diego County Board of Supervisors has recently approved additional expenditures of $437,000 to upgrade and build out a system throughout their county.

“The safety of my firefighters and the communities they protect is my priority, so having more information about a fire before we encounter it is an added safety measure that benefits our first responders,” San Diego Fire-Rescue Chief Brian Fennessy said. “Having access to a live view of our highest fire risk areas will greatly improve situational awareness, our coordination with CALFIRE and allow for quicker response times, better response strategies and faster evacuation orders to ensure our communities are better prepared in the face of a wildfire.”

Future Plans

“Clearly, more systems are needed throughout the west,” Kent said. “I’m happy with the AlertTahoe and BLM Wildland systems as prototypes –but there are plenty other areas that are in dire need of this technology.”

Kent and his team, along with Neal Driscoll at UC San Diego, have their eye on northern California, the Sonoma/Napa area, which was devastated by fire in 2017, and hope to start this spring on building capacity there. Fire camera sites in southern Idaho and Oregon are also funded as Kent, and College of Science partner Ken Smith, work with Doug Toomey at the University of Oregon to move northward in 2018.

“It’s not too late for the North Bay – or an AlertNorthBay – as well over 80 percent of the region remains unburned; and much of the 20 percent that burned could burn again with large swaths near the Tubbs, Atlas and Nuns Fires, which haven’t burned in 150 years. It’s scary.”

“All this must change if we are going to respond to fires in the urban-wildland interface, or fires after an earthquake,” Kent said. “With one of the driest years on record, following the wettest year (2017) – it’s a dangerous cocktail for 2018. Big timber fires such as the Rim and King fires may be a consequence of this unusual weather pattern.”

A nearly 3000-acre fire near Bishop, California in mid-February may be a harbinger for what is ahead in 2018. With this in mind, groups from the three universities are scrambling to get as many cameras into the wilderness and wilderness/rural interface as possible before fire season 2018 peaks.