Some of the most water-efficient plants do an unexpected thing at night. They take up carbon dioxide at night instead of during the warmer daytime, which improves efficiency of water use and adaption to semi-arid and arid climates.

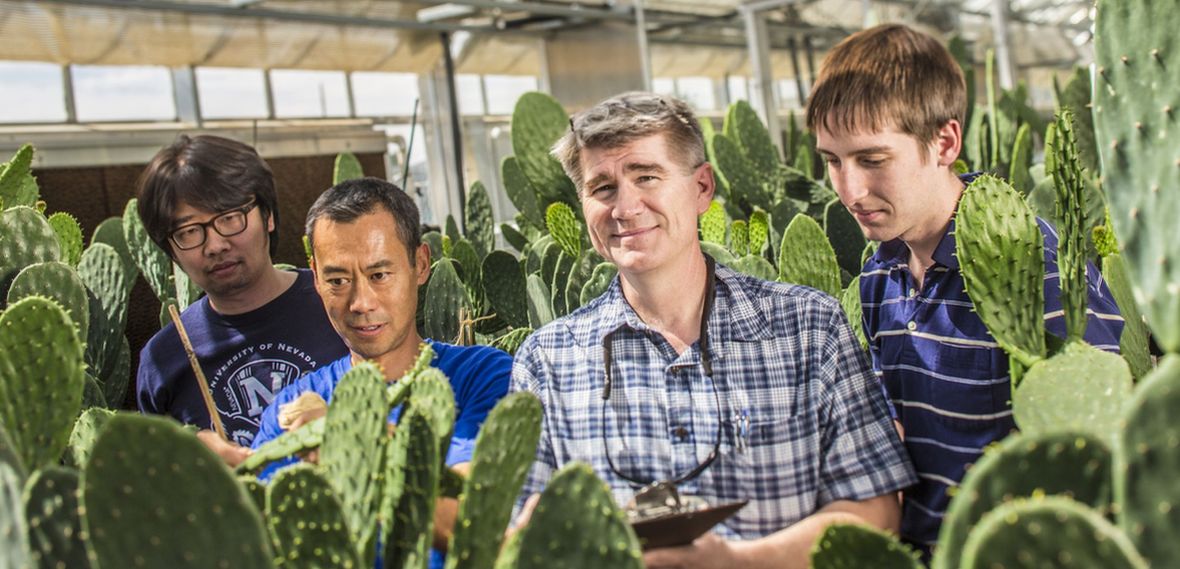

John Cushman is one of the world's leading researchers on the molecular genetics of this specialized type of photosynthesis, which is known as crassulacean acid metabolism or CAM photosynthesis. His research and plant molecular-genetics program at the University of Nevada, Reno are nationally and internationally recognized, and have made important contributions to understanding and developing more water-efficient plants. In recognition of this, the foundation professor of biochemistry and molecular biology within the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Natural Resources will receive the 2017 Nevada Regents' Researcher Award.

"CAM used to be thought of as a curiosity: a weird, esoteric thing that a few desert plants do," Cushman said. "It was a biological curiosity, but wouldn't you want to have this biological application apply to more plants to improve water-use efficiency?

"There was no inkling early on that this would have the impact it is having. Now, people are realizing the importance of this," he said.

After completing his master's and doctoral degrees in microbiology at Rutgers University, Cushman was awarded a post-doctoral fellowship in plant biology by the National Science Foundation. Through that fellowship, 30 years ago he began working at the University of Arizona, Tucson on what would become the focus of his career - plant stress and CAM plants such as agave and cactus.

Cushman has served as principal or co-principal investigator on research projects totaling more than $28 million in grant funding, has published more than 150 peer-reviewed papers and non-peer reviewed book chapters and lay publications. He currently serves as principal investigator on a multi-institutional, $14.3 million grant-funded project supported by the U.S. Department of Energy to explore the genetic mechanisms of CAM. The five-year project, now in its final year, is innovating understanding of drought tolerance in desert-adapted plants and application of this knowledge to biofuel crops. The project includes a $7.6 million grant award to the University of Nevada, Reno, with sub-awards to researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the University of Newcastle, and the University of Liverpool.

Through this and other grant-supported projects, the Cushman laboratory team is sequencing the genomes of several CAM plants and applying genome-editing technology to further improve their water-use efficiency. In one discovery through the DOE project, the leaf anatomy of the plant was changed, which increased its drought and salt tolerance.

In their nomination of Cushman for the award, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Chair Claus Tittiger and Professor Gary Blomquist note the increasing relevance of Cushman's research program for sustainable agriculture and water use, especially in the face of global climate change.

"Currently, approximately 40 percent of the world's land area is considered arid, semi-arid or dry sub-humid, with precipitation amounts that are inadequate for most conventional agriculturally important C3 or C4 (photosynthesis) crops," they wrote. "Prolonged drought and over-reliance on groundwater for crop irrigation has led to the depletion of aquifers in the US and across the globe. The development of more drought tolerant or water-use efficient crops should positively impact the future of agriculture in the state while promoting the wise use of limited water resources in Nevada and in arid states throughout the western U.S."

{{RelatedPrograms}}

For the past dozen years, Cushman has served as director of the University's biochemistry graduate program, which is an interdisciplinary collaboration in the Molecular Biosciences among the Cell and Molecular Biology Program and the Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology and Physiology Program within the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Natural Resources, the College of Science and the School of Medicine. The directorship exemplifies two aspects of higher education that Cushman values: the overlap between research and education and the increasing importance of multidisciplinary collaboration.

Cushman has witnessed and appreciates the evolution of research from single-investigator programs to larger, comprehensive programs.

"Large genome sequencing and bioinformatics projects need large teams," he said. "The technology is such that you can't be an expert in all of the research methodologies involved. We need and rely upon good collaborators."

As for his commitment to education and students, Tittiger and Blomquist wrote, "Dr. Cushman has made significant contributions to graduate education. He has not only mentored an impressive number of doctoral students and postdoctoral scholars over his career, many of whom have gone on to realize successful careers as independent scientists, but also he has been integral to maintaining the high quality of the biochemistry graduate program throughout his tenure as Graduate Program Director."

Cushman remains excited about the future and sees the field of synthetic biology as the next frontier. He also is enthusiastic about contributing to the University's expanding research and teaching presence in dryland, sustainable agriculture.

"With Nevada being the driest state, we'd like to become known for our growing expertise," Cushman said.

The Nevada Regents' Research Award is presented annually to one faculty member across the institutions of the Nevada System of Higher Education. An NSHE selection committee reviews nominations from the institutions and recommends an honoree to the Nevada Board of Regents' Academic and Student Affairs Committee for approval. The recipient receives an award amount of $5,000.

So, what does this honor mean to Cushman? Always humble, he said, "The more we can show we are having impact, the better for our students, college, University, state, country and science."