Turkey is about as far from Reno as one can get, situated on the other side of the world, but for one researcher, it’s just as much home as Reno is. Jessie Clark, an associate professor in the Department of Geography, conducts research with Kurdish women and this work has taken her to Turkey since 2005. Clark spends most of her time there in Diyarbakir, in southeast Turkey. It’s a predominantly Kurdish city, known as Amed, by Kurds.

“A lot has changed, with domestic politics in Turkey, but also broader geopolitics in the region,” she said.

Much of the Middle East is currently experiencing escalating conflict, but a recent peace process between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) initiated this summer is giving some optimism for peace.

“U.S. interest and attention are almost exclusively focused on the ongoing conflict in Gaza, but there are other important inflection points in the region,” Clark said.

In March, the PKK declared a unilateral ceasefire, which may draw decades of fighting to a close, though many of the people Clark has worked with over 20 years have told her that they are wary.

“There’s very little trust, but there’s a lot of hope,” she said.

The current process follows a century of political instability in the region.

At the end of World War I, the Middle East was divided into spheres of European and Turkish influence. The Kurdish population was spread across four states, with the largest group residing in Turkey. Ongoing struggles for Kurdish rights, both peaceful and violent, ensued, escalating in the 1980s when the PKK was established. In 2000, a 15-year conflict ended with the leader of the PKK imprisoned. Clark, who teaches courses in political geography and geography of the Middle East, began working in the region in the early 2000s.

In 2015, a youth movement within the PKK took up arms against the Turkish state in urban areas, breaking a two-year peace process and reigniting conflict. That would be the last year Clark would visit Turkey for seven years. Between the 2015 violence, an attempted coup in 2016, and the COVID-19 pandemic, Clark wasn’t able to return until she took a sabbatical in 2022.

A friendship sustained from halfway around the world

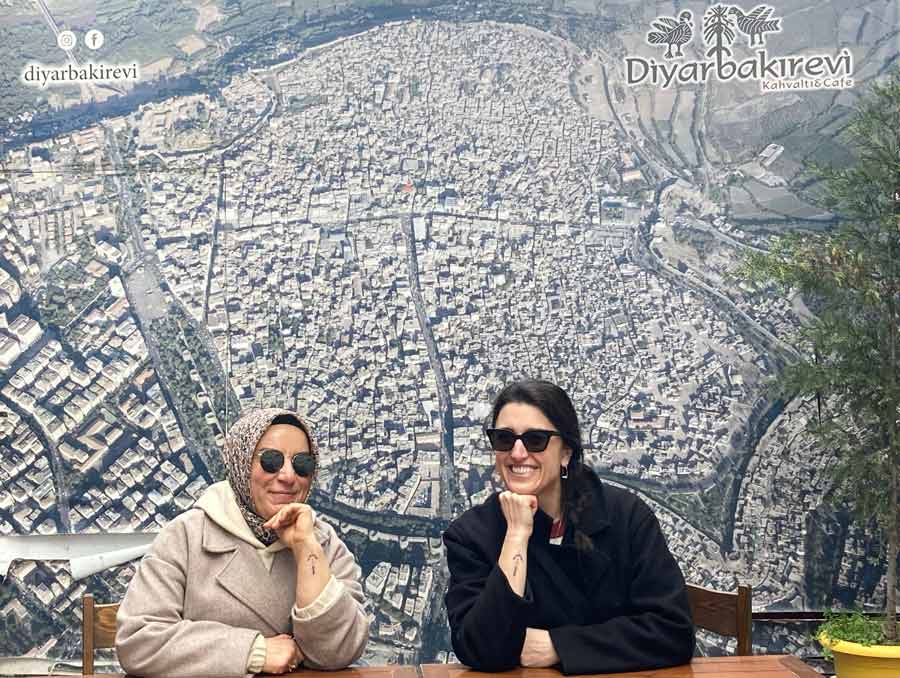

When Clark visits Turkey, she stays with a longtime collaborator and friend, Saadet Altay. Likewise, Altay is a frequent visiting scholar in the Department of Geography at the University of Nevada, Reno. When Clark first visited Diyarbakir in 2005, she realized that much of the work the Turkish government was doing in the region was development for women. She decided to focus her research on these programs. In Diyarbakir, she visited the local university looking for an interpreter who was a woman and spoke Turkish, Kurdish and English, “which was a big ask!” Clark said.

“Somebody knew somebody who knew somebody who put me in touch with Saadet,” Clark said. “She was taking English classes at the time that we met, and we couldn’t even communicate. My Turkish was terrible, my Kurdish was non-existent, her English was awful,” (Saadet will tell you that, Clark noted).

The two went to Altay’s house to talk more, and Altay likes to say that Clark “never left.”

“It was fate,” Clark said. “She’s my best buddy, her family became like my family.”

Altay and Clark began working together in the Kurdish neighborhoods. Altay’s focus was on women’s religiosity and Clark’s work was focused on development programs. They have since combined their respective interests in theology and geography to study religious identity and practices amongst Kurdish women and youth, and the two became close friends.

“Those seven years I couldn’t return to Turkey, it was really hard,” Clark said. “Thank God for WhatsApp.”

Changed landscapes

During the years Clark wasn’t able to visit Turkey, two of the neighborhoods where she conducted research were completely destroyed, displacing 22,000 people and killing 200. The Housing Authority of the Turkish government has taken on a large role in rebuilding in the region.

During what they call “engaged walks” Clark and Altay speak to the people they encounter and ask them about living and working in the post-conflict landscape. Some of the displaced people returned to the neighborhoods when homes were rebuilt after negotiating for an affordable mortgage.

“A lot of people who were living in those neighborhoods until 2015 have been displaced during rural conflict in the 80s and 90s between the PKK and the Turkish government,” Clark said, “so [there are] lots of iterations of displacement of people in and out of these neighborhoods.”

Over the last two decades, Clark observed a shift in Turkey’s political landscape, with more centralized state governance. A Congressional Research Service Report published in September highlights that some U.S. and EU officials have voiced concerns regarding democratic practices and governance trends in the country.

“It’s made doing research much harder,” Clark said.

Some of her current work explores the experiences of people who lived in those neighborhoods before the conflict, after the conflict and now, but she emphasized that she is very mindful of what she publishes and the risk that places on people who contributed to the research. She thinks a lot about the ethics of international collaborations in politically sensitive environments and how to balance the safety of people with accurately documenting their experiences.

“I don’t have an easy answer for that,” Clark said.

Making adjustments

Clark said she felt like she lost some momentum in her research due to the seven years she was unable to visit Turkey. Not only had she lost the practice of organizing working groups in Turkey, but so much had changed in Diyarbakir in those years. In the interim, Clark worked on a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded community-based research project on housing insecurity in the Hispanic/Latino community in Reno. Clark noted there are parallels in the daily insecurities immigrant communities face here with those of displaced families in Diyarbakir.

Clark has been intentional about learning the new landscape in the neighborhoods that she worked in, which has been a slow process. Her research will rely on the relationships she and Altay have established over the past two decades. It’s focused more on day-to-day life for Kurdish people in a post-conflict environment and the salience of religion in people’s lives, particularly for women and youth.

Clark and Altay also noticed global trends impacting both the US and Turkey. The male loneliness epidemic has led young men in Turkey to the “manosphere” just as it has in the U.S.

Clark had a grant from the American Research Institute in Turkey, which was funded by the U.S. State Department. The funding was delayed in February, and it was officially cancelled this month. She paid for her most recent trip to Turkey out of pocket and fortunately can stay with Altay and her family. But the grant funds she planned to use to provide incentives for the people participating in her research study, which is how most studies recruit participants, were from the State Department award. Internal monetary awards like the Ozmen Institute for Global Studies Faculty Research Award, which she received in 2023, have helped bridge some of the funding gaps.

“That was really helpful,” she said.

Clark plans to return to Turkey in January. She is cautiously optimistic for what a peace process could bring, but peace in Turkey and in the region will take time.