This story was originally published on the Hitchcock Project for Visualizing Science news site. The Hitchcock Project, an initiative of the Reynolds School of Journalism, aims to train students and scientists in accurate and engaging forms of science communication. Read more science news at HitchcockProject.org.

Desplácese hacia abajo para ver español. Translation by Vanesa de la Cruz Pavas.

Golden dawn light filters through the pine needles overhead on a chilly September morning at Manzanita Lake Campground in Lassen Volcanic National Park. At a picnic table, Philipp Ruprecht and his colleague Mike Gardner boiled water for an essential morning elixir – coffee.

From an outside perspective, this may appear like any other weekend camping trip with a group of outdoorsy folks enjoying the final days of summer, but it is more than that.

This weekend, Ruprecht, a volcanologist and associate professor from the University of Nevada, Reno, Gardner, an engineer and assistant professor from UC Davis, and graduate student Jakob Scheel are venturing into the field at Lassen to hunt for a specific kind of rock that will help give insight into the events leading up to volcanic eruptions.

“We're studying here these rocks that are about 1,000 years old,” Ruprecht said. “They have parts in them that we call mafic enclaves. They are the magma that potentially triggered a volcanic eruption.”

At Lassen Volcanic National Park in California, University of Nevada, Reno scientists are studying volcanic rock formations to learn about the events leading up to eruptions. Credit: Kat Fulwider.

At Lassen Volcanic National Park in California, University of Nevada, Reno scientists are studying volcanic rock formations to learn about the events leading up to eruptions. Credit: Kat Fulwider. Like chocolate chips in cookie dough, mafic enclaves appear as darker-colored areas inside of lighter-colored volcanic boulders. Credit: Kat Fulwider.

Like chocolate chips in cookie dough, mafic enclaves appear as darker-colored areas inside of lighter-colored volcanic boulders. Credit: Kat Fulwider.Today, the team plans to collect samples of these enclaves and their crystals, which they will later take back to their lab at the University to analyze.

“We can't drill into a volcano and so as a volcanologist, we need to kind of get there by, for example, looking at crystals that basically were there at the site of where all action happened and then we can read in that record of these crystals,” Ruprecht said.

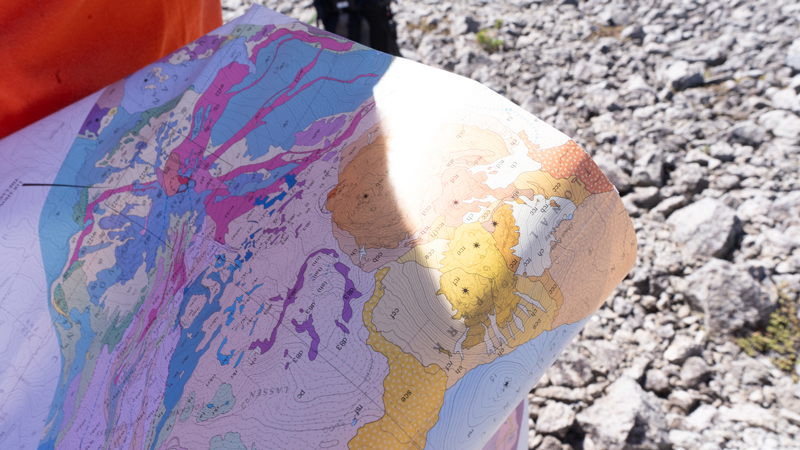

Unfurling a colorful map, Ruprecht pointed to some orange splotches in the center. Here, about 1,000 years ago, a string of six volcanic eruptions took place to create a formation known as the Chaos Crags. This is today’s destination.

“What we want to understand is by having six different eruptions, we can basically take different snapshots in time on how this magmatic system changed in that time period,” Ruprecht said.

Researchers examine the scenery on a colorful geologic map. Credit: Kat Fulwider.

Researchers examine the scenery on a colorful geologic map. Credit: Kat Fulwider.Packs were loaded with sledgehammers, water bottles filled, sunscreen slathered, and the group of researchers set off into the wilderness. Ruprecht, clad in a faded red sun shirt, led the way up a trail at the edge of the campground and off into the forest. The terrain, first moderately flat, grew steeper as the group hiked on. Soon the forest gave way to a moonscape terrain, the pine needles and manzanita bushes replaced by crunchy ash-colored cinder.

“Us volcanologists get excited the less biology there is around,” Ruprecht said.

Up and up the party hiked, traversing across ecoclines and topo lines to the base of a line of cliffs, where large boulders rested, each cracked in a radial pattern. These cracks occurred as the volcanic boulders cooled, from the outside in, Ruprecht explained.

For Ruprecht, this landscape is a map of the past, if one only knows where to look. Rock formations and crystalline structures act as landmarks in time, all fitting together as pieces to a puzzle of the formation of the Earth.

The crew climbed higher, up loose scree and over shifting rock. After cresting a saddle between two peaks, a formation known as “Dome A” came into sight, a wall of boulders and teetering rocks. The party picked their way through the boulder field in a single-file line, carefully navigating the loose terrain. They crossed a narrow pass and went down the other side, into a boulder field that was a promising place for enclaves, and perhaps more importantly, had shade.

Immediately, Ruprecht, Scheel, and Gardner dropped their packs and began scouring the landscape for the rocks in question — mafic enclaves. They appeared as dark blobs of rock within lighter grey rock faces, like easter eggs turned to stone.

The trio of scientists was transported into a parallel world of geology with a language of their own: “We don’t want amphibole. We want the plagioclase… What about this one?... Yeah, look at that plag… We should get some of the host material on this one too…”

Ruprecht found his target of choice on the face of a massive block of stone. He snapped a photo with his iPad and took a GPS location of the sample site.

Expertly, Ruprecht chipped away a sample of rock, then pulled a hand lens on a necklace of string out from beneath his shirt. Squinting, he held the lens up to his eye and rotated the rock this way and that as the sun glinted off the crystal faces.

“Yes,” Ruprecht said. “Probably pyroxene. See those tiny black blocky crystal right next to plagioclase?”

These crystals, though tiny, may just be what is needed to unravel the biggest questions about the planet’s past – and future. By reading the crystal record, Ruprecht and Scheel are attempting to learn what conditions inside the magma chamber were like leading up to the volcanic eruptions.

After this weekend’s expedition, the scientists will bring these samples back to the University’s Microbeam Lab, where they will analyze their chemical makeup using a specialized piece of equipment called an electron microprobe. By analyzing trace amounts of elements found within these crystals, the scientists can better understand the temperatures and conditions within the magma chamber.

Scheel retrieved another sample with a satisfying smack-thud from his sledgehammer, then marked it with a sample number. The next forty minutes were a cacophony of hammering and discussion, as a routine of photography, hammering, examining, and logging samples ensued.

After a quick lunch break in the shade, everyone shouldered their packs to move on to the next sample site, “Dome B.” The party funneled back through the spire pass and skirted the semi-circle crater of a hopefully extinct vent, beyond which Lassen Peak rose, dominating the skyline.

The slumbering giant lay in a tepid peace. Lassen Peak, the southernmost peak in the Cascade range, last erupted explosively in 1915, jettisoning volcanic ash into the sky and sending it up to 200 miles eastward. This and other previous eruptions left lasting marks on the landscape, reflected in namesakes such as the “devastated area” and “the jumbles.”

Although volcanoes can be very destructive and have an inherent danger tied to them, Ruprecht sees them in a different light.

“They are places where life is created and the reason why sometimes life is destroyed, because volcanoes are the places where the land is resurfaced,” Ruprecht said. “New nutrients are being brought to the Earth's surface, and you can basically have new life coming from that.”

At Dome B, the group collected additional samples. In the late afternoon, the group divided the rock samples into their packs and began the slow descent through the boulder and scree fields back toward camp.

As they hiked, the hot afternoon sun gave way to the golden light of evening, the alpenglow setting Lassen Peak ablaze in brilliant shades of pink. A cool twilight soon enveloped the land, and stars began to emerge. As the trail grew darker, the party switched on headlamps to illuminate their path. Finally, the smells and glows of campfires greeted the weary explorers back at Manzanita Lake Campground.

A pot of “lasagna stew” cooked over a fire assuaged the sounds of grumbling stomachs, which yielded to laughter and stories of adventure – and misadventure – in the name of science from the sides of volcanoes around the world. Then, off to bed in sleeping bags and tents under dark and starry skies.

These days in the field, though few and far between, are essential to all that comes next. With dusty boots and a vehicle full of rock samples, the group returned to the University, where they would spend the next few months processing and analyzing the crystals found in these rocks.

“The field research is important because on the one hand it is the inspiration of questions that I want to address and that I take then into the lab,” Ruprecht said. “On the other hand, in a reverse view, it is the place of ground truthing against which I like to check laboratory and model results.”

For more information on Philipp Ruprecht and his work, please visit the website of the University’s Volcano Research Group.

For more information on this project, as well as Spanish versions of each video, please visit the Rock Whisperers on the Hitchcock Project website.

Un día en la vida de un vulcanólogo

La luz dorada del amanecer se filtra entre las agujas de pino en una fría mañana de septiembre en el campamento del lago Manzanita, en el Parque Nacional Volcánico Lassen. En una mesa de picnic, Philipp Ruprecht y su colega Mike Gardner hierven agua para preparar un elixir esencial de la mañana: café.

Desde una perspectiva externa, esto podría parecer como cualquier otra excursión de campamento de fin de semana con un grupo de amantes de la naturaleza disfrutando los últimos días del verano, pero es mucho más que eso.

Este fin de semana, Ruprecht, vulcanólogo y profesor asociado de la Universidad de Nevada, Reno; Gardner, ingeniero y profesor asistente de UC Davis; y el estudiante de posgrado Jakob Scheel, se aventuran al campo en Lassen para buscar un tipo específico de roca que podría ofrecer pistas sobre los eventos que preceden a las erupciones volcánicas.

“Estamos estudiando aquí estas rocas que tienen alrededor de mil años”, dijo Ruprecht. “Tienen partes que llamamos inclusiones máficas. Son el magma que, potencialmente, desencadenó una erupción volcánica”.

Las inclusiones máficas son masas oscuras y densas de roca rica en magnesio y hierro, atrapadas dentro de grandes rocas volcánicas de color más claro. Se forman cuando el magma caliente proveniente de zonas más profundas de la corteza terrestre irrumpe en una cámara de magma más fría preexistente, solidificándose y quedando suspendido en el magma anfitrión. Para los vulcanólogos, son cápsulas del tiempo que conservan un registro cristalino de lo que ocurrió en el interior de la Tierra hace miles de años.

Hoy, el equipo planea recolectar muestras de estas inclusiones y de sus cristales, que luego llevarán de regreso al laboratorio en la universidad para analizarlas.

“No podemos perforar un volcán, así que como vulcanólogos necesitamos encontrar otras formas de acceder a esa información. Por ejemplo, observando los cristales que estuvieron, básicamente, en el sitio donde ocurrió toda la acción, y a partir de ellos podemos leer ese registro”, explicó Ruprecht.

Desplegando un mapa colorido, Ruprecht señaló algunas manchas naranjas en el centro. Allí, hace aproximadamente mil años, ocurrió una cadena de seis erupciones volcánicas que dieron lugar a una formación conocida como Chaos Crags. Ese es el destino de hoy.

“Lo que queremos entender es que, al tener seis erupciones distintas, podemos obtener diferentes muestras en el tiempo sobre cómo cambió este sistema magmático durante ese periodo”, dijo Ruprecht.

Las mochilas se cargaron con mazos, las botellas se llenaron de agua, el bloqueador solar fue aplicado, y el grupo de investigadores partió hacia la naturaleza. Ruprecht, vestido con una camisa de sol roja ya desteñida, encabezó el camino por un sendero en el borde del campamento, adentrándose en el bosque. El terreno, al principio moderadamente plano, se volvió más empinado a medida que el grupo avanzaba. Pronto, el bosque dio paso a un paisaje árido parecido a la luna, donde las agujas de pino y arbustos de manzanita fueron reemplazados por ceniza volcánica suelta y de color grisáceo.

“Nosotros, los vulcanólogos, nos emocionamos más cuanta menos biología hay alrededor”, dijo Ruprecht.

El grupo siguió ascendiendo, cruzando líneas topográficas hasta la base de una cadena de acantilados, donde reposaban enormes rocas volcánicas, cada una con grietas que formaban patrones radiales. Estas grietas, explicó Ruprecht, se formaron cuando los bloques volcánicos se enfriaron desde el exterior hacia el interior.

Para Ruprecht, este paisaje es un mapa del pasado, si se sabe dónde mirar. Las formaciones rocosas y las estructuras cristalinas funcionan como hitos en el tiempo, encajando entre sí como piezas de un rompecabezas sobre la formación de la Tierra.

El equipo siguió subiendo, escalando sobre escombros sueltos y rocas inestables. Al coronar un paso de montaña, apareció ante ellos una formación conocida como “Domo A”: una pared de rocas gigantes y piedras tambaleantes. El grupo avanzó en fila a través del campo de rocas, navegando con cuidado el terreno suelto. Cruzaron un estrecho paso y descendieron por el otro lado, hacia un campo de rocas que parecía un lugar prometedor para encontrar inclusiones y, quizás más importante en ese momento, tenía sombra.

De inmediato, Ruprecht, Scheel y Gardner dejaron caer sus mochilas y comenzaron a inspeccionar el paisaje en busca de las rocas en cuestión: inclusiones máficas. Aparecían como manchas oscuras incrustadas dentro de superficies rocosas grises más claras, como huevos de Pascua convertidos en piedra.

El trío de científicos parecía transportado a un mundo paralelo de la geología, con un lenguaje propio: “No queremos anfíbol. Queremos plagioclasa… ¿Y esta?... Sí, mira ese plag… También deberíamos tomar algo del material huésped de esta…”

Ruprecht encontró su objetivo en la cara de un enorme bloque de piedra. Tomó una foto con su iPad y registró la ubicación GPS del sitio de muestreo.

Con destreza, Ruprecht extrajo una muestra golpeando la roca, luego sacó una lupa de mano que colgaba de un collar de cuerda bajo su camisa. Entrecerrando los ojos, sostuvo la lupa frente a su rostro y giró la roca de un lado a otro mientras el sol se reflejaba en las caras cristalinas.

“Sí”, dijo Ruprecht. “Probablemente piroxeno. ¿Ves esos pequeños cristales negros y angulosos justo al lado de la plagioclasa?”

Estos cristales, aunque diminutos, podrían ser justo lo que se necesita para desentrañar las grandes preguntas sobre el pasado —y el futuro— del planeta. Al leer el registro cristalino, Ruprecht y Scheel buscan comprender cuáles eran las condiciones dentro de la cámara magmática antes de las erupciones volcánicas.

Después de la expedición de este fin de semana, los científicos llevarán las muestras al Laboratorio de Microsonda de la universidad, donde analizarán su composición química utilizando un equipo especializado llamado microsonda electrónica. Al examinar pequeñas trazas de elementos presentes en estos cristales, podrán comprender mejor las temperaturas y condiciones que existían dentro de la cámara magmática.

Scheel extrajo otra muestra con un satisfactorio golpe-sordo de su mazo, luego la marcó con un número de referencia. Los siguientes cuarenta minutos fueron una cacofonía de martillazos y conversaciones, mientras se desarrollaba una rutina de fotografiar, martillar, examinar y registrar muestras.

Después de una pausa para el almuerzo a la sombra, todos se cargaron nuevamente las mochilas al hombro para dirigirse al siguiente sitio de muestreo: “Domo B”. El grupo volvió a pasar por el estrecho paso entre las rocas y rodeó el cráter semicircular de lo que se espera sea un conducto volcánico ya extinto. Más allá, el Lassen Peak se alzaba imponente, dominando el horizonte.

El gigante dormido yacía en una calma tibia. Lassen Peak, el pico más al sur de la cordillera de las Cascadas, tuvo su última erupción explosiva en 1915, cuando expulsó ceniza volcánica al cielo que llegó hasta 200 millas hacia el este. Esa y otras erupciones anteriores dejaron huellas visibles en el paisaje, reflejadas en nombres como el “área devastada” y “los escombros.”

Aunque los volcanes pueden ser muy destructivos y conllevan un peligro inherente, Ruprecht los ve bajo una luz diferente.

“Son lugares donde se crea la vida y la razón por la que a veces la vida se destruye, porque los volcanes son los sitios donde la tierra se renueva,” dijo Ruprecht. “Nuevos nutrientes son traídos a la superficie de la Tierra, y básicamente puede surgir nueva vida a partir de eso.”

En Domo B, el grupo recolectó muestras adicionales. Ya entrada la tarde, el equipo guardó las muestras de roca en sus mochilas y comenzó el lento descenso a través de los campos de rocas y escombros hacia el campamento.

Mientras caminaban, el caliente sol de la tarde dio paso a la luz dorada del atardecer, con el resplandor alpino incendiando el Lassen Peak en brillantes tonos rosados. Un fresco crepúsculo pronto envolvió la tierra y las estrellas empezaron a aparecer. A medida que el sendero se oscurecía, el grupo encendió sus linternas frontales para iluminar el camino. Finalmente, los olores y las luces de las fogatas recibieron a los exploradores cansados de vuelta en el campamento del lago Manzanita.

Una olla de “guiso de lasaña” cocinada sobre una fogata aplacó los sonidos de estómagos gruñendo, que pronto dieron paso a risas y relatos de aventuras —y desventuras— en nombre de la ciencia desde volcanes alrededor del mundo. Luego, a dormir en sacos de dormir y carpas bajo cielos oscuros y estrellados.

Estos días en el campo, aunque pocos y esporádicos, son esenciales para todo lo que viene después. Con botas polvorientas y un vehículo cargado de muestras de roca, el grupo regresó a la universidad, donde pasarían los próximos meses procesando y analizando los cristales encontrados en estas rocas.

“La investigación de campo es importante porque, por un lado, es la inspiración de preguntas que quiero abordar y que luego llevo al laboratorio,” dijo Ruprecht. “Por otro lado, y de manera inversa, es el lugar de verificación en terreno contra el que me gusta contrastar los resultados de laboratorio y de los modelos.”

Para más información sobre Philipp Ruprecht y su trabajo, por favor visita el sitio web del Grupo de Investigación Volcánica de la Universidad de Nevada, Reno: http://www.volcanology.info/

Para más información sobre este proyecto, así como versiones en español de cada video, por favor visita: https://hitchcockproject.org/projects/rock-whisperers/