As paleoecologist, Foundation Professor and Gibson Professor of Geography Scott Mensing describes it, Tuscia, Italy looks straight out of a movie set. Located on the western side of the country near the Apennine Mountains with its green rolling hills spotted with olive groves and oak woodlands, the landscape appears beautifully pristine. However, that idea of a "pristine" landscape is exactly what Mensing and his research partner Gianluca Piovesan of Tuscia University have been researching for the past decade. Their February 2018 published paper, recently featured on nature.com, unearths a more complete picture of the drivers of past environmental change and the direct impact humans have had on shaping what we today see as a natural landscape.

2700 years of change

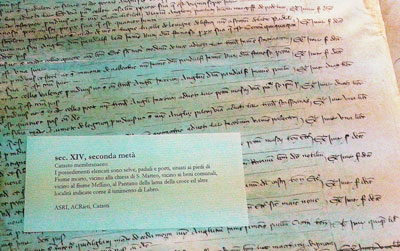

Mensing and Piovesan used written records dating back to the Roman Period, such as this late medieval document, and compared them to samples of sediment and pollen cored from the lakes to develop a detailed history of the landscape changes over time.

In and around Tuscia, Italy, there exist long written historical records of human presence dating back to the Roman Period. When compared with a scientific record of historical ecology produced from coring lakes for sediment and pollen, Mensing and Piovesan have been able to develop a more complete and precise picture of human impact on the environment over time.

"While we speak in a global sense of humans impacting the environment, the actual impacts are made at a local level by individuals making decisions that are largely influenced by very local socioeconomic conditions," Mensing said.

What they found was drastic and rapid change. The picturesque Italian landscape of today has no resemblance to any previous landscape of the last 2700 years. In fact, an entirely new forest ecosystem has emerged. Abrupt changes to the landscape occurred with every regime change, mirroring the sociopolitical and demographic priorities of the population.

"The ‘nature' we see today is the result of a long legacy of past land use changes implemented by prior communities who had very different priorities in mind," Mensing said. "The landscape sometimes accumulates these impacts so that no one variable, such as climate, or ecologic interactions, create a landscape."

These drastic changes tied directly to the politics of the time happened on the order of decades not centuries, rapidly changing the landscape, regime change after regime change. And while the relatively new landscape of today may appear to be natural, much of the humid and wet forest ecosystem that existed prior to human interaction with the environment has been lost.

"Restoring these ecosystems is essential in this era of global warming to ensure not only the conservation of biodiversity, but also to enhance the ecosystem services like water resources, and to mitigate climate change impact thanks to the remarkable capacity of the wet and mesic forest to store carbon and release water in the atmosphere," Piovesan said.

Pictured here is one of the last remaining remnants of a wet forest in Tuscia, Italy. Before human interference with the landscape, this forest ecosystem thrived.

Act local, think global

Such detailed historical records do not exist in many places, limiting the location sites for this kind of research. However, Mensing and Piovesan's findings can inform environmental policy and land use planning in communities around the world.

"If we want to make changes in our impacts on the environment, there are two ways to do this," Mensing said. "One is through global treaties that create global impacts (such as the Montreal Protocol which eliminated CFCs in response to the ozone hole issue). Another is through local land management to preserve local environments. Even if laws are written at a national level, the land management is executed at a local level, and we want to understand what local circumstances drive real change in the environment."

Mensing and Piovesan plan to extend their research in Tuscia, and they have identified a possible new research site in Tuscany, Italy where medieval archives extend back to about the year 700 AD.

"It takes more than one site to generally convince people that what we are seeing might be a more general pattern," Mensing said. "This type of work is very different from the global modeling studies that tend to get a lot of attention about how humans impact the environment at a global scale. We are trying to tease out the actual human activities that directly cause a specific change."

Beyond the research

(From left) Scott Mensing, Gianluca Piovesan, Emanuele Ziaco and Emanuele Presutti pose for a photo while coring Lungo Lake in Italy for sediment.

With over a decade working in the Italian countryside, Mensing became accustomed to the Italian way of life, which of course includes Italian food and everything that goes with it.

"I love good food and Gianluca also loves good food," Mensing said. "There was a fantastic camaraderie around meals that happened repeatedly and was a real highlight of working in Italy."

Mensing describes a four-course Italian lunch in-between coring sessions, spreads of home-cured meats, fruits and baked goods offered up by almost strangers, and hours of eating, drinking, and talking in broken English and Italian during dinner at the mayor's house.

The food was well deserved as the researchers would regularly spend full days on a raft, from dawn to dusk, trying to extract as much sediment from the lake as possible in order to uncover the history of the landscape.

"It is hard work that requires special attention to every detail at the same time," Piovesan said. "but the passion for research and the magical atmosphere of the rural places around the lakes has made it an unforgettable memory."

Right now, Mensing and Piovesan are preparing a new proposal to be submitted to the National Science Foundation with the hope of continuing their work reconstructing the history of the Italian landscape.

"Thanks to a meeting with Scott Mensing ten years ago," Piovesan said, "it became possible to realize a dream that, as a forest ecologist, I have had for a long time: reconstructing the history of forests in central Italy in an area that has been the cradle of classical culture."