Across Nevada’s rangelands, hauling barbed wire and setting fence posts remains a necessary, albeit labor-intensive, task for ranchers. Now, with help from University of Nevada, Reno researchers, some are testing “virtual fencing,” a GPS system that lets them guide cattle remotely in real time using handheld software – no physical barriers required.

The technology allows ranch managers to design grazing rotations that experts from the University’s Extension and Experiment Station units, both part of the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources, say benefit the ecosystem by protecting riparian areas, boosting forage for wildlife and reducing wildfire fuel, all critical benefits for Nevada’s fragile rangelands.

“Virtual fencing technology isn’t brand new, but it’s emerging in a way that finally makes sense on working rangelands,” said Paul Meiman, an Extension state specialist who also conducts research as part of the Experiment Station. “It offers tremendous promise for both federal land management agencies and ranchers because it provides a level of flexibility in grazing management that we’ve never had before, especially when managing landscapes with sensitive riparian areas.”

With support from the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service, Meiman, also a professor of rangeland and ecology management in the College’s Department of Agriculture, Veterinary & Rangeland Sciences, has teamed up with ranches to test the technology across tens of thousands of acres of rugged Western terrain.

How does virtual fencing work to manage grazing in Nevada rangelands?

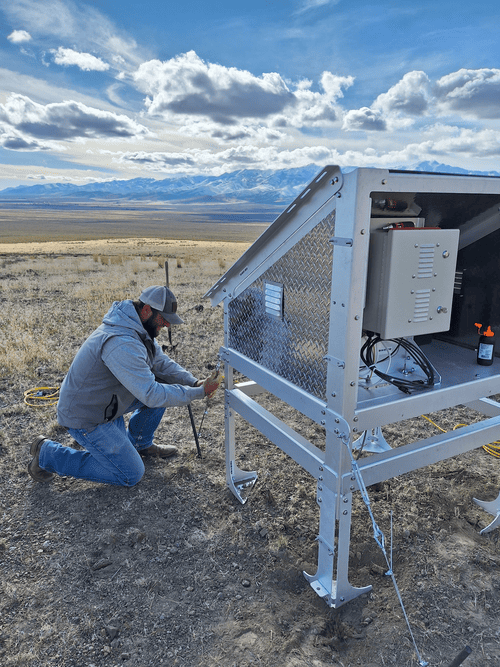

At Maggie Creek Ranch, nearly a quarter-million acres of private and public land in Elko, Meiman collaborated with ranch manager Jon Griggs to “train” a herd of 200 yearling heifers. After a virtual fence company helped Meiman and his team install two tower-based receiver stations, which can each transmit signals up to 10 miles depending on terrain, the team outfitted each animal with a GPS-enabled collar and set digital grazing boundaries in the software.

“As a cow approaches the invisible boundaries, the collar emits a beep as a warning,” Meiman said. “If the animal persists into the restricted zone, it delivers a mild pulse along with another beep. Over time, the cattle learn the pattern and adjust their movements on their own.”

In what resembles a Pavlovian feat, the herd was sufficiently conditioned within three days.

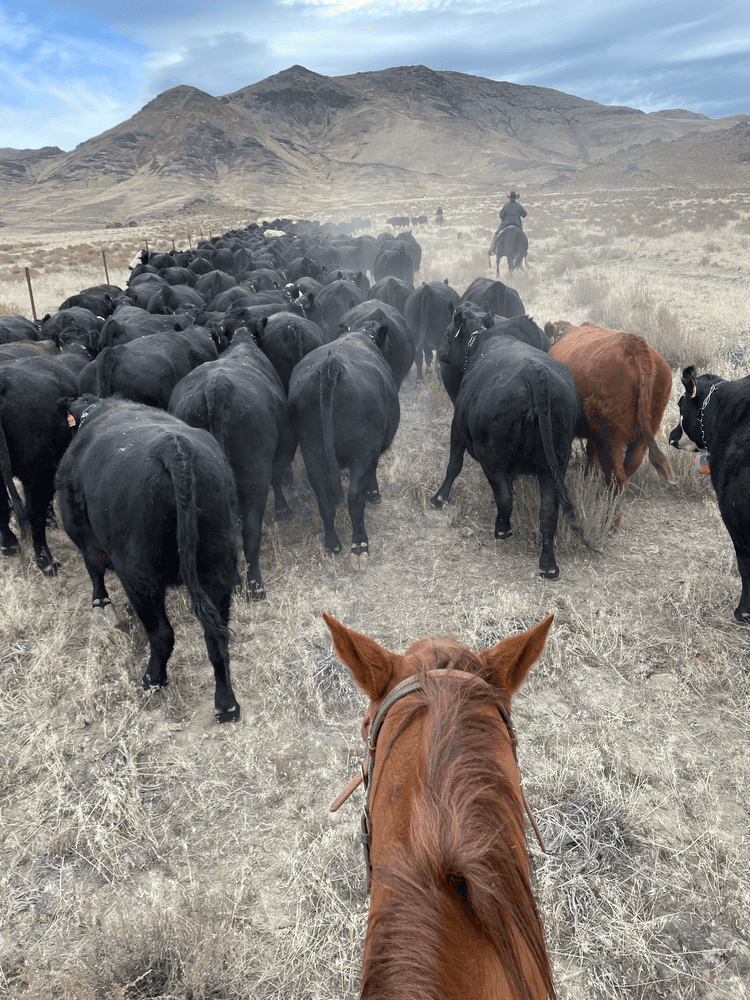

“Virtual fencing gave us a level of control that we don’t typically get on large, open rangeland,” Griggs said. “We were able to place cattle exactly where we wanted them and move them through the pasture more efficiently. For operations like ours, it shows real promise, especially in areas where traditional fencing or herding just isn’t practical.”

After three years of participation, Griggs said the technology improved grazing efficiency while supporting ecological balance on the ranch, where mule deer, wild turkeys, waterfowl, porcupines and raccoons share habitat with cattle and horses. A conservation leader, Maggie Creek Ranch has earned the National Environmental Stewardship Award for its land management practices, while Cottonwood Ranch in Wells, Nevada, which has been instrumental in the virtual fencing project, received the 2025 Rangeland Stewardship Award from the Bureau of Land Management.

Using virtual fencing to control cheatgrass, reduce wildfire risks and improve forage quality

While Meiman, Griggs and a crew from Cottonwood Ranch evaluated virtual fencing from small to large working pastures, a separate University research team tested the technology at a participating ranch in Paradise Valley, Nevada, to direct grazing on invasive cheatgrass species to protect native grasses, improve forage for livestock and reduce wildfire risks. The team included Tracy Shane, assistant professor in the College’s Department of Agriculture, Veterinary & Rangeland Sciences, her student Austin Lemons, a graduate student in the Department’s animal and range management sciences program, and researchers from the U.S. Forest Service.

“Cheatgrass is a persistent challenge for rangelands because it sprouts early, outcompetes native perennial grasses and quickly depletes soil moisture and nutrients,” said Lemons, who, in addition to his full-time studies, is an active officer in the Army National Guard and conservation manager at the Dayton Valley Conservation District. “Once established, it forms dense, dry stands that are highly flammable, increasing wildfire risk.”

The project initially planned to use traditional barbed-wire fencing, but logistical constraints and archeological concerns prompted the shift to virtual fencing.

“We started our collaboration with a brief training period to introduce the cattle to the virtual collars and help them learn and respond to the technology’s invisible boundaries,” Lemons said. “From there, ranchers managed the movements of their herds by adjusting grazing patterns and providing feedback to refine the system through an app.”

Lemons and Shane deliberately grazed cattle on cheatgrass in the fall rather than the typical spring timing.

“The advantage of this approach is that after summer, cheatgrass often greens up again while most native plants do not, directing cattle to focus primarily on the invasive species,” Lemons said. “This has the potential to reduce the seed bank from fall-germinated cheatgrass, remove dry litter that fuels wildfires and reduce quality of germination sites for cheatgrass reestablishment in the spring.”

Early results and what comes next

The experiment showed promising early results.

Across both research projects, ranchers contributed by tracking herd movements and collecting data. At one study site, the targeted grazing treatment reduced cheatgrass biomass from 400 pounds per acre to just over 100 pounds per acre, reducing the carry-over litter and fuels by 75%.

Ranchers also reported practical advantages.

Concentrating cattle in narrow grazing zones encouraged animals to eat a broader mix of plants rather than just their preferred species. The result was more uniform pasture use and healthier rangelands overall.

“By guiding cattle to work through each grazing area before moving on to the next, we immediately saw reduced pressure on preferred grasses and better long-term sustainability of forage resources,” Griggs said.

Because meaningful ecological changes typically take years to emerge, Lemons and Shane track short-term indicators such as stubble height, streambank conditions and vegetation patterns that support native species.

“Any range management research involving changes in grazing practices usually takes three to 10 years before we start seeing real, measurable changes in the vegetation,” Shane said. “That’s why we rely on short-term indicators to track progress, but the real ecological results come with time, patience and continued commitment.”

Cost challenges of widespread adoption of virtual fencing

While virtual fencing offers many benefits, its cost and operational challenges may slow adoption at ranches such as Maggie Creek and Cottonwood. Each base station linking collars to the management app costs roughly $10,000, in addition to a service fee of $60 per animal per year. In addition, dense tree cover and rough topography can cause connectivity issues with the virtual fence system, occasionally limiting real-time monitoring of cattle locations and the ability to change virtual fence locations.

Support from the Nevada Agricultural Foundation, Nevada Division of Forestry, Nevada Department of Wildlife, U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management has helped make virtual fencing accessible by providing collars and base stations for participating ranchers. Looking ahead, the University’s project teams aim to expand pilot testing of the technology for wider adoption across Nevada’s rangelands.