Mental illness exists in a space scientists are still working to understand. Unlike many medical conditions with targeted treatments, mental health disorders often respond unpredictably, varying widely from person to person.

In honor of May’s Mental Health Awareness Month, Mitchell Omar, assistant professor of human health and disease in the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, reminds us that while treatment can be uncertain, we’re not powerless in this first-person article. He offers key insights into the biology of mental illness and practical steps we can take to protect our mental health and reduce its impact.

From his early fascination with the brain to his research on synapses and schizophrenia, Omar shares a hopeful look at what science is uncovering – and how everyday choices can help strengthen our minds.

I have always been fascinated by the brain. It is incredible to think that everything we do is powered by tiny cells inside our skulls.

Alongside that fascination, I have also been drawn to understanding what happens when the brain does not work as expected. That curiosity has shaped my research focus today: mental illness.

Mental illnesses such as depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and substance use disorders affect how we think, feel and behave. About one in five adults in the U.S. lives with a mental illness, a personal struggle that costs society nearly $500 billion each year.

So, what causes mental illness?

The short answer is “it’s complicated.” There is no single cause. Instead, these disorders result from a mix of environmental factors (what happens to us) and genetic factors (what we are born with).

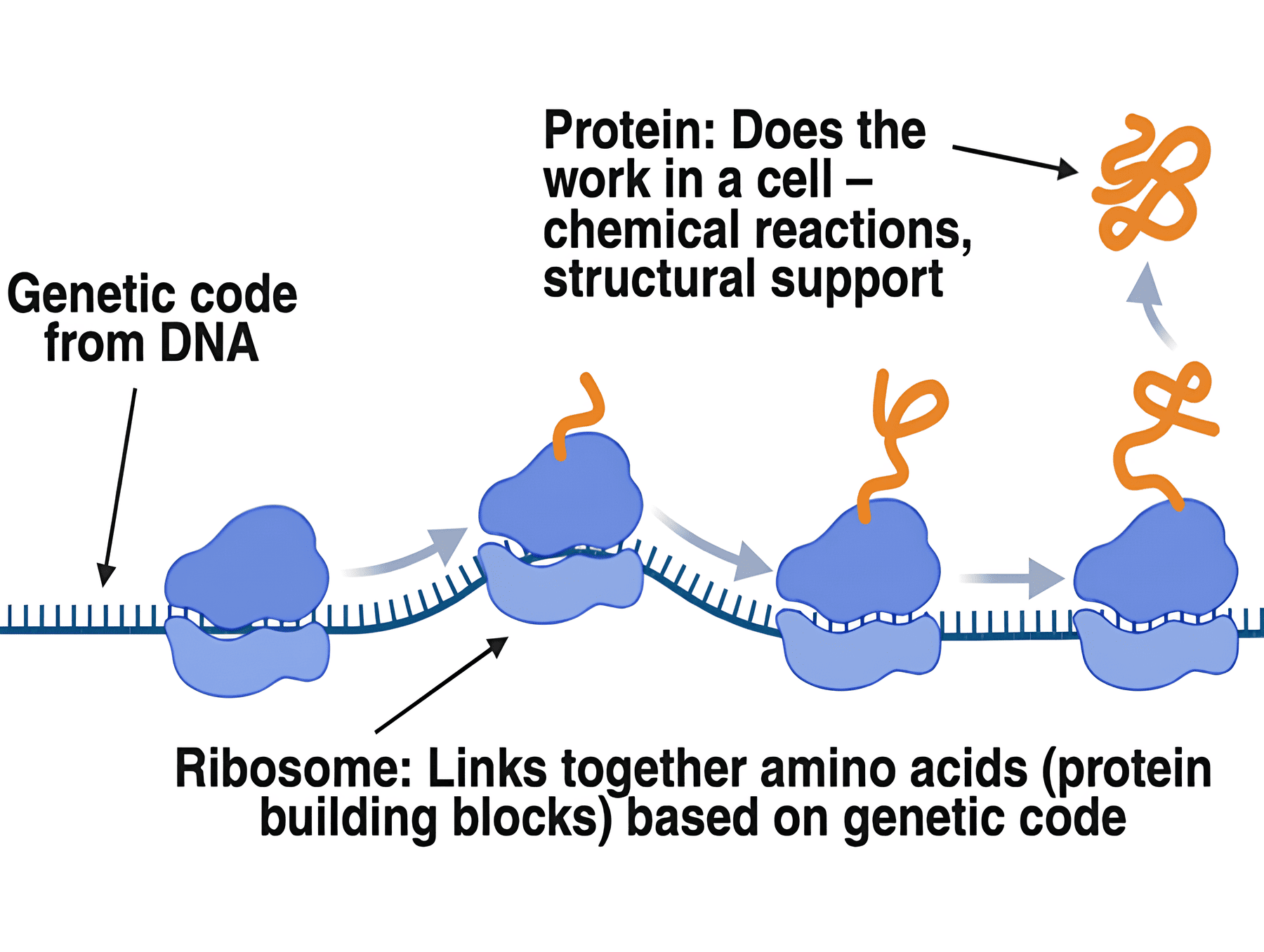

Environmental factors include life experiences, trauma, stress and even exposure to certain chemicals. Genetic factors relate to the code that makes us who we are: our DNA. This code is made up of more than 3 billion chemical building blocks, forming about 20,000 genes that guide how our bodies and brains function.

While we can’t change our genetics, we can reduce environmental factors that affect mental health starting with everyday habits.

Sometimes, tiny changes in this DNA code, even just a single chemical out of place, can increase the risk of illness. Most of these changes are harmless. But when researchers look at complex conditions like schizophrenia, we see hundreds, sometimes thousands, of small DNA differences that each might raise the likelihood of developing the disorder.

That is what drives me to keep asking questions, not just about how the brain works when everything is going well, but what goes wrong when it does not. Because the more we understand, the better we can help.

Each cause affects our brains a little differently. For example, why are socially isolated people more likely to struggle with depression or addiction? It is partly because isolation can lower levels of serotonin and dopamine, brain chemicals that help regulate our mood and motivation.

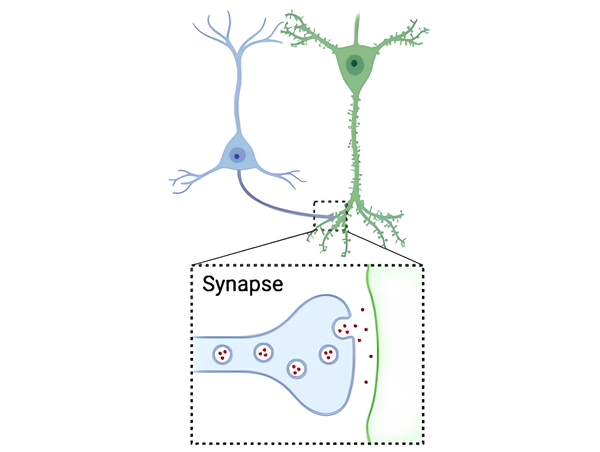

Let’s talk about synapses – the brain’s tiny chat rooms

A common observation across many causes of mental illnesses is how they affect the communication and interaction between our brain cells. Our thoughts, movements and even senses all rely on brain cells talking to each other through tiny contact points called synapses.

Many of the genes linked to mental illness play a role in keeping these synapses working properly. When there are changes or “mutations” in those genes, the synapses can weaken or break down altogether.

In adolescence, the brain is still building systems that stabilize synapses. Disrupting that process with drugs or alcohol can cause long-term changes more easily in younger people than in adults.

Early in my research career, I studied one such gene tied to schizophrenia. I discovered it plays a key role in helping synapses stay stable as the brain matures – especially from adolescence into adulthood when schizophrenia symptoms begin to appear.

This gene produces a protein called Laminin α5, which sits in the space between brain cells. In healthy brains, synapses anchor themselves to this protein, keeping communication strong. But in some people with schizophrenia, genetic changes may disrupt Laminin α5, making those synaptic connections less stable.

When brain cells can’t stay connected, the entire system starts to falter, and that can lead to symptoms we recognize as mental illness.

Yes, you can protect your synapses

While we can’t change our genetics, we can reduce environmental factors that affect mental health starting with everyday habits.

Sleep

Sleep is one of the best things you can do for your brain. Learning and memory rely on tiny changes in your synapses, and good-quality sleep helps those changes stick. Without enough rest, synapses struggle to adapt, making it harder to retain what you’ve learned.

What you eat

Healthy eating and regular movement also protect brain function. You don’t need to overhaul your life. Even small increases in daily activity can noticeably improve your mood and mental clarity.

Substance abuse

Avoiding substance abuse is especially important for teens. In adolescence, the brain is still building systems that stabilize synapses. Disrupting that process with drugs or alcohol can cause long-term changes that are harder to reverse in younger people than in adults.

Manage stress

In small doses, stress can help you focus. But when it lingers, high cortisol levels can damage synapses and even shrink brain cells. While stress is hard to avoid, its impact can be managed. Sleep, exercise and good nutrition all help, but so does setting time aside for real rest. Taking real breaks, where you mentally detach from work matters. Mindfulness, meditation, yoga or simply doing nothing for a few minutes can help reset your system.

Try new things

Trying something new helps your brain stay flexible. It doesn’t have to be big. Rearranging your routine, taking a new route, or learning a game or hobby all help. Shaking up your habits nudges your brain out of autopilot and strengthens synaptic connections.

What is my lab doing about mental illnesses?

In our lab, we are studying a recently discovered gene, AKAP11, which is linked to both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This gene produces a protein found in synapses and may help control how they grow or shrink when brain cells communicate.

While researchers work to understand the biology behind mental illness, there is a lot we can all do in the meantime to protect our brain health. Slight changes add up – and supporting your synapses starts with how you live each day.