Hendaia (Hendaye) and Donostia (San Sebastián) are two Basque cities located twenty kilometers apart but separated by two European educational systems. In Iparralde (the northern Basque Country), students from secondary schools know who Jean Racine is and probably a good number of them are able to name two works of the author and one in every 100 has read some of his works. In Donostia, his counterparts have studied Gonzalo de Berceo’s work and may mention some of his writings.

Furthermore, everyone in Hendaia knows that not knowing Racine is synonymous with “ignorance”, because culture is what is learned in schools. And everyone in Donostia knows that whoever does not know Berceo is a tremendous airhead because that is what is taught in the classrooms. But few high school students in Hendaia have heard of Berceo, and few students in Donostia know who Racine was. However, students from both sides of the border have something in common: none of them know who the Basque writer Joan Batista Elizanburu was.

“The language of the constitution and of the laws will be taught to all, and the multitude of corrupt dialects, the last remnants of feudalism, will be forced to disappear: necessity dictates so”

One of the first theorists of the monolingual way of seeing the world was Antoine de Rivarol who in his work Sur l’universalité de la langue française (On the Universality of the French Language), of 1783, defended that French was superior to the rest of the European languages due to its “genius” or “inner spirit”, which endowed it with greater clarity, rigor, expressive capacity, and rationality. In the author’s opinion it was very difficult to be an enlightened person without speaking the French language.

Some authors went a step further and argued that if knowing French was the only way to be educated, speaking other languages was a form of ignorance and, they concluded, it was a “patriotic duty” to eradicate the rest of the languages spoken in the French Republic. These ideas were easily spilled into politics during the French Revolution: Not speaking French was considered a counterrevolutionary activity, an act of treason.

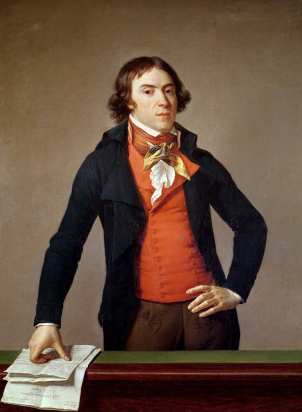

Bertrand Barère

Bertrand BarèreCharles M. Talleyrand was one of the first to defend these ideas on September 10, 1791: “The language of the constitution and of the laws will be taught to all, and the multitude of corrupt dialects, the last remnants of feudalism, will be forced to disappear: necessity dictates so”. To achieve this objective, it was necessary to teach the language on a compulsory basis to children through the creation of a universal institute of education in which all classes were taught in “the first language of the State”.

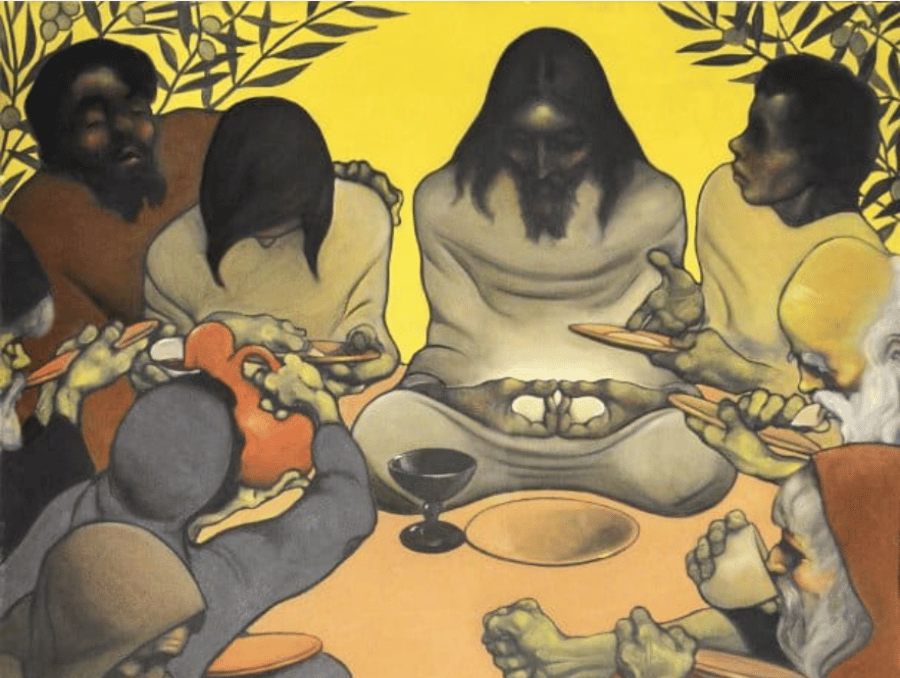

1794 was the year of the linguistic terror (la terreur linguistique), a historical moment inspired by Bertrand de Barère and Henri Grégoire, under the political leadership of Robespierre, Danton, Marat, and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just. All of them criminals, engineers of the dictatorship of fear. Grégoire declared before the Committee of Public Health on July 30, 1793 that it was necessary to create schools that, like “hospitals of the human spirit”, would heal the mental wounds of those who did not speak French.

Eradicating diversity

His message was unequivocal: “Eradicating this diversity of languages that prolongs the infancy of reason and the old age of prejudice is more important than you think. Their destruction will be immediate.” Bertrand Barère presented on January 28, 1794, a report to the Convention on the imposition of the French language through teaching and by prohibiting the use of other languages. The author also spoke clearly: “Federalism and superstition speak low Breton, emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German, the counterrevolution speaks Italian and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let’s destroy these instruments of prejudice and error.”

The foundations of the French State’s language policy were laid between June 1793 and December 1794, a despotic and unconstitutional period in which no less than twenty norms were approved that seriously affected the existence of the national languages spoken in the Republic.

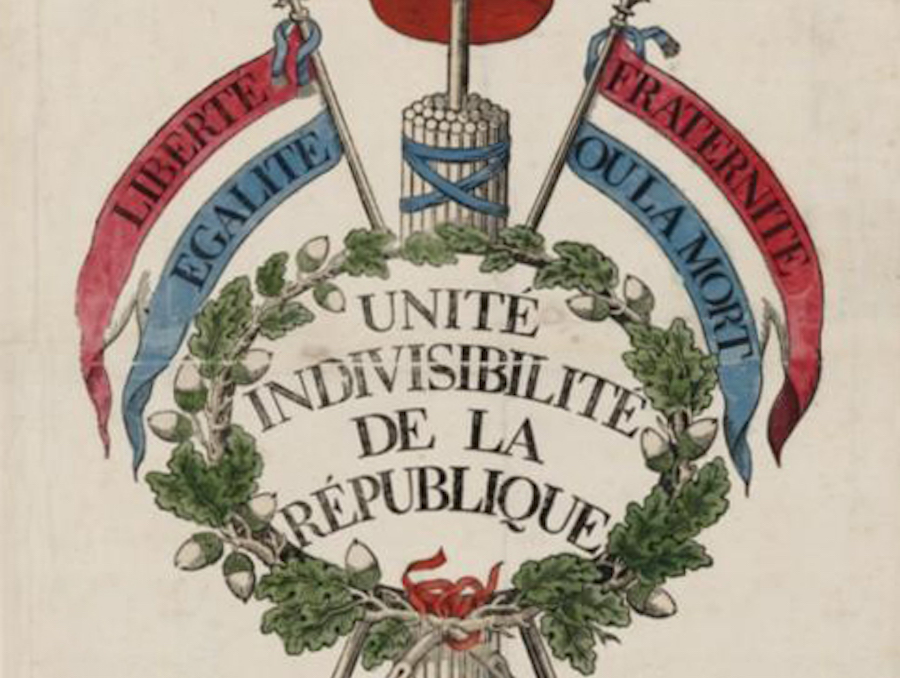

After the approval of the so-called Autumn Decrees (of 1794), the langue d’oïl was adopted as the only language of the State and it was granted the political (and not linguistic) title of Langue française (French language), a symbol of the unity and indivisibility of the French Republic. Culturally, the Jacobin party made reference to the langue d’oïl as “our language” to the detriment of the rest of the languages and Romance varieties (such as Occitan or Langue d’oc) that came to be considered “patois”, “jargons”, or “feudal languages”. This policy is known as the choix jacobin (the Jaconine choice).

Under the motto, “that in all corners of the Republic classes will be taught but in French”, the decree of October 21, 1793, is one of the first legal norms on the compulsory nature of education in a single language. The decree of July 20, 1794, imposed the prescriptive use of French and the prohibition of all other languages in the State administration: “No public act may be written (or registered) other than in the French language, in any part of the territory of the Republic”.

The Basque language, not useful

I emphasize that the discourse of these authors and the content of these rules is crystal clear and blunt because there are those who continue to repeat the old adage that the Basques stopped speaking Basque because they understood that it was not useful.

“[I]t must be the doctrine of our schools, and the only method of teaching, that the language that is thought [at schools] be one and that it be the Castilian language”

In view of the thousands of legal regulations on language policy, it is obvious that the Basque citizens learned through prohibitions—and often through prison and torture—that speaking their language was dangerous and if they wanted something from the Administration they had to do it in French. As the prefect of the department of the Low Pyrenees put it in 1846, the “Frenchization” of Basque schools was a necessary strategy: “Our schools in the Basque Country are particularly designed to replace the Basque language with French”.

This model of “language policy” was adopted by Spanish liberalism. The political objective was to promote the Castilian linguistic monopoly by excluding the rest of the languages from all areas of the public administration and the education system. The board of public instruction, established by the courts of Cádiz and directed by Melchor Gaspar de Jovellanos, established in 1813 that “it must be the doctrine of our schools, and the only method of teaching, that the language that is thought [at schools] be one and that it be the Castilian language”. As in France, the Castilian language adopted the political title of “Spanish language” and became the only language of the State.

Parallel to the loss of economic and political freedoms between 1789 and 1839, the squandering of the cultural rights of the Basque people placed Euskara (the Basque language) in a precarious situation at the beginning of the 20th century. This was due to the linguistic policies whose purpose was to blow up the pillars of the Basque national identity, either by prohibiting, restricting, or simply bypassing the rights of the persons who belonged to this national group. Unfortunately, the legal recognition of national languages and cultures was completely unknown in both states until practically the 21st century. It has been called “language policy” but all of this is, by definition, cultural genocide.

In April 2021, the French Assembly approved a bill allowing primary schools to teach the majority of school subjects “in a regional language” and the rest in French. But the minister of education appealed the bill, arguing that the so-called “immersive teaching” won’t allow children to reach the appropriate skills in French. Accordingly, France’s Constitutional Council ruled that teaching in “minority languages” such as Basque, Breton, Catalan and Corsican, is “unconstitutional”.

The ruling of the Constitutional Council of the République has not surprised anyone: It is a new milestone in the context of 230 years of linguistic terror.