There are two types of science communicators: communicators drawn to science and scientists who develop a passion for communication. Elizabeth Walsh is the latter. Graduating with her Ph.D. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology this May, Walsh studies mosquitoes and viruses, but after graduating in May, she plans to pursue a career in science communication.

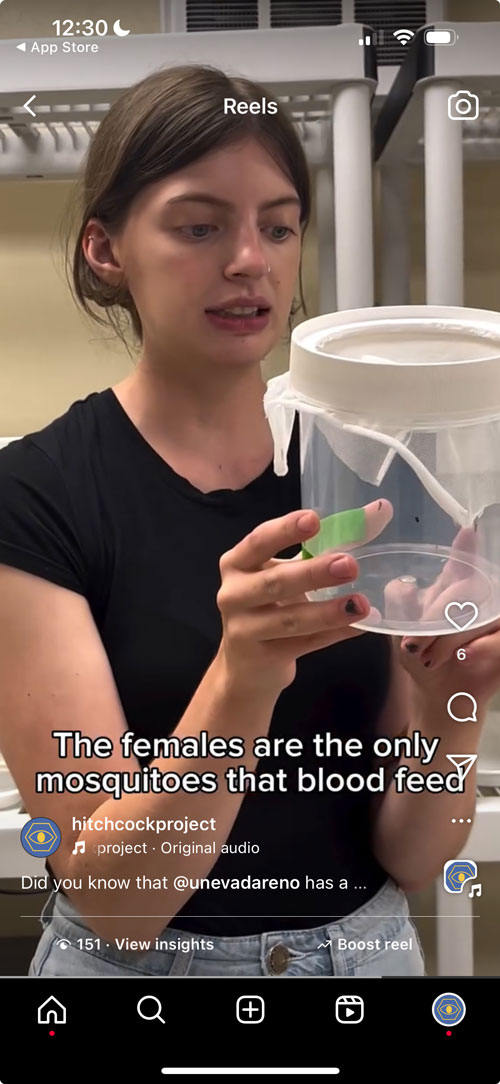

Beyond her research, Walsh has a deep passion for storytelling. Seeking to better communicate complex science, she took classes with the Hitchcock Project for Visualizing Science at the Reynolds School of Journalism and was selected for the prestigious American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Mass Media Fellowship last summer to report for the Idaho Statesman. She defines the fellowship as transformative and encourages others to apply. The fellowship provided hands-on experience in science writing and continued support through a six-month mentorship. Currently, she is being mentored by a health editor at Scientific American. After graduating, Walsh is moving to Washington D.C. to report for Chemical & Engineering News as part of the outlet's Editorial Fellowship Program.

Below, Walsh shares how she transitioned from studying mosquito cells to writing about them — and her advice on becoming a better science communicator.

Hitchcock Project: What is your research now, and how did you end up doing that research?

Walsh: Right now, I study antiviral pathways in mosquitoes. Mosquitoes spread a lot of viruses to people, like dengue, Zika, and West Nile. These viruses are unique because they can infect both people and mosquitoes. We know a lot about how they infect people, but much less about how they infect mosquitoes. I study the proteins in mosquito pathways that allow the virus to infect them, as well as how mosquitoes fight off these viruses.

Another unique aspect of these viruses is that once they infect a mosquito, they stay with it for life. However, the virus doesn’t cause significant harm to the mosquito, which creates an interesting dynamic: how much the mosquito’s immune system fights the virus and how much it doesn’t.

HP: Do you like the work you do now?

Walsh: Yeah, I really do. I've always liked bugs. A lot of people are afraid of mosquitoes or don’t like being around them, but I’ve grown really fond of them. I enjoy taking care of them and observing them every day. I also think their biology and the viruses they carry are fascinating, so I really enjoy the research I’ve been doing.

HP: What does a day in your research process look like?

Walsh: My days are a little complicated because, on top of doing research, I’m also the Vice President of the Graduate Student Association and a teaching assistant. I start my day pretty early with those responsibilities.

When I was actively conducting research—because now I’m in my dissertation writing phase—I would spend almost all day writing. During my research phase, I took care of the mosquitoes by feeding them and giving them blood once a week. However, most of my work was molecular biology, so I had limited time with the mosquitoes.

A lot of my research involved cell culture, where we keep mosquito cells in a flask and conduct experiments on them. It’s much easier to work with cells than live mosquitoes, which may not blood-feed, get testy, or die unexpectedly. With cells, I can manipulate genes to express less and then infect them with viruses to observe what happens. That kind of experiment has been the bulk of my research for the past five years.

HP: How did you first become interested in science communication?

Walsh: I’ve always loved writing, but for a long time, I didn’t realize science communication was a career option. I thought I had to choose between science and writing, so I chose science.

During my PhD, though, I realized that my work had become very niche—I study just three proteins and know everything about them, which can get monotonous. I started reading more about other people's research and saw that science news was a major field. I spent a lot of time reading science news and wondered if I could be one of the people writing it.

The first science communication experience I had was writing for MicroBites, a blog that simplifies immunology and microbiology for non-specialists. I really enjoyed it, so I started looking into fellowships, which led me to the AAAS Mass Media Fellowship. I also reached out to the Hitchcock Project to take science communication classes. After just one class, I was hooked—I loved interviewing people and writing. That’s how I got into science communication.

HP: What skills did the Hitchcock Project class help you develop?

Walsh: I definitely learned how to interview people. I’m really glad I took that class before my fellowship. I also learned how to write and report a news story, which I had never done before. As a scientist, it's easy to think that people want all the niche technical details, but that class taught me how to tell a story without getting bogged down in those details. Essentially, I learned the fundamentals of journalism.

HP: How did you learn about the AAAS Mass Media Fellowship?

Walsh: I was researching how to transition from lab work to writing about science, and the fellowship was one of the first things I found. I read more about it and thought it was amazing that they give researchers the opportunity to write about science, even if they don’t have much experience in journalism.

HP: What was the fellowship experience like?

Walsh: I loved it. It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had. This program allows PhD and master’s students—and some undergraduates—who conduct scientific research to transition into writing about other people's research. The program places around 20 fellows at different news sites across the country. Some are at general news sites; others are placed at more science-focused outlets like Scientific American.

Writing about science as a scientist can be great, but it can also be really hard. You might know more than the average person, which makes some things easier, but it also makes other things harder. Other scientists might talk to you like you’re an expert, and then you end up with terrible quotes that don’t translate well into a story.

After being selected, we were flown to Washington, D.C., for a crash course in science journalism. We learned how to pitch stories, conduct interviews, write effectively, and identify credible sources.

Then, I moved to Boise, Idaho, for 10 weeks to work at the Idaho Statesman, where I wrote about two science stories per week relevant to the region. I received fantastic mentorship from my editor, who was incredibly patient and helped me grow as a writer. What I loved most was that I was treated like a reporter—I found stories, wrote them, and had them published. It was an amazing experience.

HP: What are some of the stories you remember working on?

Walsh: I think my favorite story that I worked on was about geothermal energy in Idaho. It took me the longest to report—about seven weeks—interviewing people and gathering information. It was about why Idaho is such a good place for geothermal energy. Idaho has very low geothermal development, and there’s a policy aspect to that. It was my first time having to learn about policy, which was challenging.

I also really liked the more science-focused articles I wrote. I interviewed a researcher from Boise who was working on making potato chips better by improving how we process them. He was using electricity to make cutting and frying potatoes easier, which actually reduces cancer-causing agents in potato chips.

Because it's such a regional paper, I got to write a lot about the environment, which was cool—topics like wildfires, how they track wolves, and mercury in the water. Bird flu also broke out in cows while I was there, so I got to write about that, which is now very relevant.

HP: What challenges have you faced as a science communicator? How do you deal with them?

Walsh: Writing about science as a scientist can be great, but it can also be really hard. You might know more than the average person, which makes some things easier, but it also makes other things harder. Other scientists might talk to you like you’re an expert, and then you end up with terrible quotes that don’t translate well into a story.

I think the key is reminding yourself that even if you know a lot about a topic, the people you’re interviewing are still in different fields. You want to write from the perspective of someone who might not know much about the subject.

Balancing science and science communication can also be tough. For me, I’m still finishing my Ph.D., so managing my current job while also working on skills for the job I want can feel overwhelming. It’s important to be patient with yourself—you don’t have to get a job in science communication right away.

HP: What advice would you give to a student like you—someone starting in science who is thinking about transitioning into communications?

Walsh: For me, making the jump—asking people if I could write, if I could join a class, or even applying for this fellowship—was really scary. I felt like I wasn’t qualified for it. But I think people, in general, are really kind and willing to help. So I would say, just reach out and say, “Hey, I want to do science communication.” The people in this field will help you get there.