Students who signed up for Geology 461/661, a paleobiology class, got much more than they bargained for when they took a field trip to Carlin, Nevada, about 30 minutes west of Elko.

“When Dr. Noble and Dr. Bonde offered a field trip out into the Elko area to find fossils there was no way I could say no, the answer was immediately obvious to me that I needed to go,” Austin Armstrong, a recent graduate and student in the course, said.

The paleobiology course, taught in the fall by Department of Geological Sciences and Engineering chair Paula Noble and University alumnus Joshua Bonde ‘03 (biology), included opportunities for hands-on work in eastern Nevada. The two-day field trip included one day looking for marine shelly fossils near Carlin, then searching for Miocene-age (approximately 15 million years ago) mammal fossils the following day.

The previously unknown fossil mammal site was disclosed to Noble and Bonde, two of the state’s most renowned fossil experts, by a pair of rockhounding siblings before the field trip. The site was located on public lands, which was ideal for the professors, who both have permits from the Bureau of Land Management to work on and collect from public lands.

“It became apparent within the first half hour of visiting the locality that this was going to be a significant fossil site,” Noble said.

The fossil site was likely once a riverbed or a shallow lake area and contained fossils from an abundance of prehistoric animals that once roamed the Great Basin, including camels, early horses, pigs, rhinos, elephants, weasels, canines and saber-toothed cats.

“Holding the fossils in my hand, I remember struggling to imagine the world as they lived it, and to see the fossil in my hand as something that was once alive millions of years ago,” Armstrong recalled. “The experience enhanced my perspective on geologic time, opening a direct, physical connection to organisms from the distant past.”

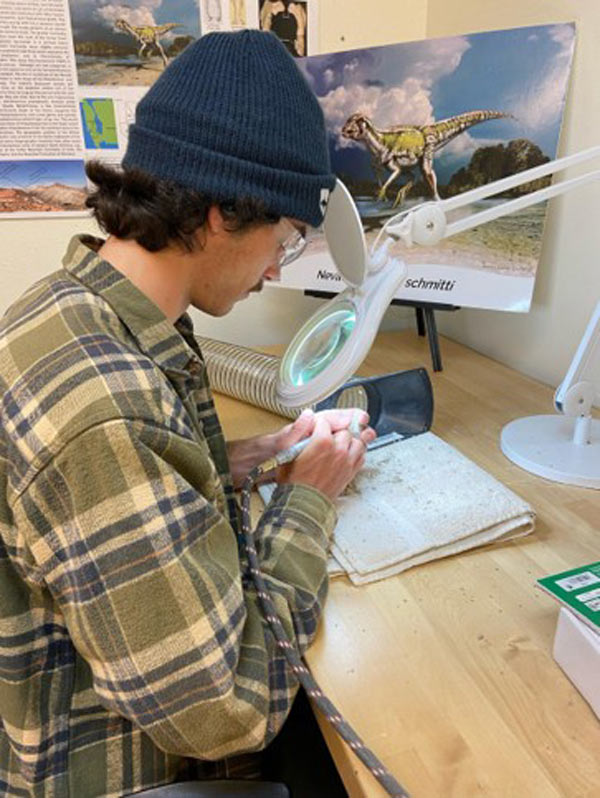

There were many fossils from a variety of species, and students recovered many teeth and limb fragments, bringing them back to the University to study further.

Finding the fossils was just the first step. The next step was to clean them and prepare them to be stored in museum collections.

“We came up with the idea of an independent study course to provide students with an opportunity to continue working with these fossils in the spring semester,” Noble said.

The undergraduate students in the paleobiology course jumped at the opportunity to see the project through.

“Much like the offering of the field trip, when professors Bonde and Noble offered for students to continue working with the fossils in an independent study class, I once again immediately knew my answer, and put my foot in the door to continue research in the spring semester,” Armstrong said.

“The students collected [the fossils], so they wanted to see how the rest of the story went,” Bonde explained.

Bonde and his wife Rebecca Hall, a geoscientist and former executive director of the Children’s Museum of Northern Nevada, established a public fossil lab at the children’s museum. The children’s museum and the Nevada State Museum established a Memorandum of Understanding which allowed students in the independent study course to continue working with the fossils. The undergraduates worked on cleaning the fossils while interfacing with the museum guests before the fossils make their way to the final repository at the Nevada State Museum across the street.

Bonde, who previously served as director of the Nevada State Museum, was able to cross the street to support students in their fossil preparation work, if they needed help.

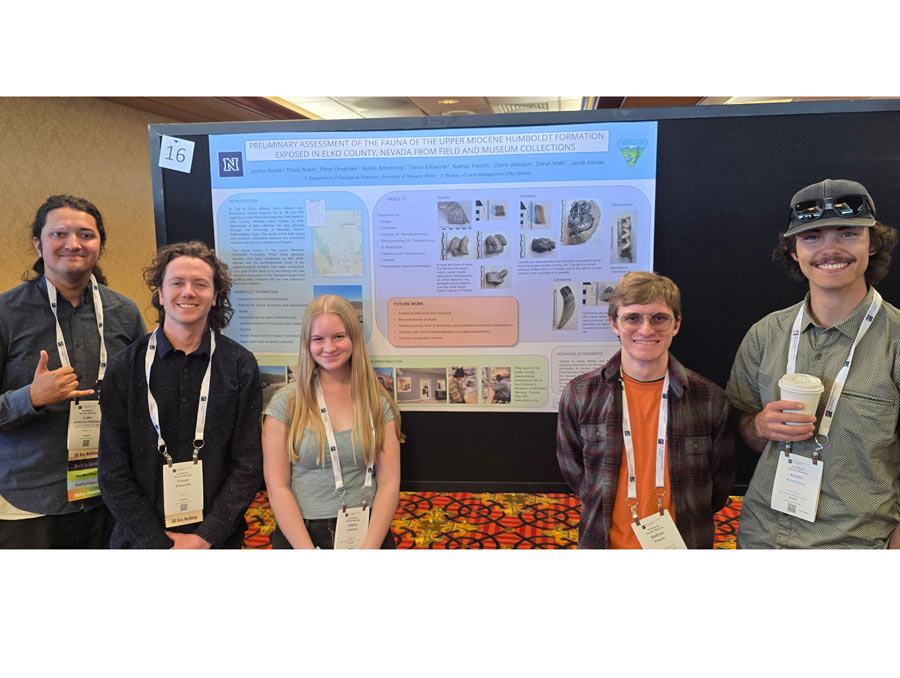

The students presented their research as a poster at the Geological Society of America regional meeting, where the students fielded some tough questions about the geology of the field site.

“Above all, Dr. Noble and Dr. Bonde’s paleobiology class provided me with an overarching connection between many of the fundamental principles I have learned in geology, and how it directly connects to the evolution and growth of life on planet Earth,” Armstrong said.

At the Reno meeting of the Geological Society of Nevada, the students “totally nailed it,” Noble said. Their revisions and studies paid off, and they even won a $50 prize for honorable mention in the poster contest. The students also presented their work at the Wolf Pack Discoveries research symposium.

“Eventually the goal is to turn that into a research paper about the biological and geological history of that part of Elko County,” Bonde said.

Noble enjoyed watching the students engage with the fossils and gain confidence in presenting their research results. For Bonde, providing students with a “rock to research” project was a full circle moment.

“This was something that I got to do when I was an undergrad, and it really helped set my career path,” Bonde said.

Two students from the class will continue to work with the fossils at the children’s museum in the fall semester, contributing to knowledge about Nevada’s prehistoric mammals millions of years after they lived and died in the Great Basin.

“The combined experience of the paleobiology class and the following independent research class was a pivotal point in my undergraduate degree where I discovered that I could very much enjoy conducting my own research and projects in the future,” Armstrong said.