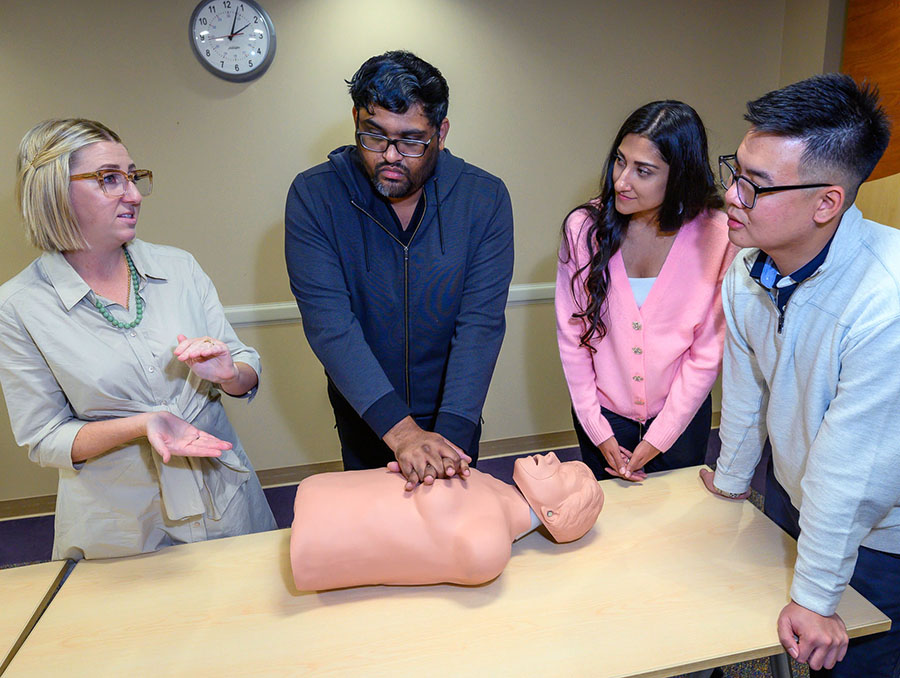

Would you know what to do if someone’s heart suddenly stopped beating? Maybe you’d recall training from work or school and begin chest compressions to the beat of “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees? Maybe you’d be afraid of hurting someone and call 911 to get professional medical help. Or, maybe you’d be overwhelmed and not know how to help. What if you were a high school athlete and one of your teammates went into cardiac arrest during practice or at a game?

Most people are more likely to call an ambulance than try to perform CPR on their own, which means fewer people survive a cardiac arrest, according to the research of Dr. Lorrel Toft, a cardiologist and associate professor at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.

More than 350,000 people in the U.S. experience an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest each year, and fewer than 11% of them survive. Being near someone who can perform CPR improves a person’s chance of survival but CPR training rates in the U.S. are low. While 43 states require high school students to learn CPR, only 30% of students can perform high-quality CPR immediately after training, and Dr. Toft’s surveys show fewer than half retain that knowledge six months later.

To make CPR training among high school students and athletes more effective and save more lives, Dr. Toft is developing interactive films and other digital media with funding from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association in collaboration with Coram Technologies. She received a two-year, $1.48 million grant from the NIH in September to use interactive digital media and game-like experiences to teach CPR to high school students. It builds off her work to create realistic, interactive films to train student-athletes to identify cardiac arrest and give CPR on the field immediately, which was funded by a three-year $400,000 grant from the AHA in 2019.

“Getting trained to give CPR is important, but we can be more efficient and effective with training as a nation,” Dr. Toft said. “I focus on high school because that’s where the opportunity lies, but there are many other applications.”

First, tackle the athletes …

Several high-profile professional athletes recently experienced a cardiac arrest on the field, including 25-year-old Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin, who received a “severe blow” to the chest at just the right time during a game in January 2023. He received CPR on the field and survived, and as a result, played in the 2023 NFL season.

Dr. Toft hopes cases such as this will draw more attention to the need for effective CPR training. Cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in high school athletes, standing at one in 50,000 to 80,000 students each year. The nature of these cardiac arrests and the potential delay in getting help on the field make high school athletics an important niche where Dr. Toft and her team can make a difference.

“We want to equip and empower athletes to be ready to respond if they ever have a teammate who collapses from cardiac arrest,” she said. “Every minute of delay to giving CPR or defibrillation decreases survival by 10%.”

High school sports teams often rely on off-field trainers or emergency first responders to aid players on the field. Dr. Toft said those seconds or minutes of waiting cost a life, and if players know how to administer CPR, they can save lives instead.

The training film her team will develop focuses on helping athletes identify the signs of cardiac arrest — to separate them from a concussion, spinal injury or other common athletic injuries — and be equipped to act fast. With additional education, teammates can feel confident in their ability to quickly assess and act on the field before medical professionals or trainers arrive.

Dr. Toft’s goal is to increase the retention of CPR skills among athletes and high school students in general, advance CPR training in high schools and eventually push the training to professional athletes.

“It’s a simple idea, but it moves the needle in a significant way,” Dr. Toft said.

… Then the world

By surveying teachers and instructors, Dr. Toft found significant variability in the way schools train students to perform CPR. With standard training, only 12% of students can perform high-quality CPR six months after training but her research also shows that interactive training methods can be more effective.

The novel interactive CPR training films developed by Dr. Toft directly engage students by showing them a scenario and pausing to ask alternating student teams direct questions. This approach ensures they engage in active rather than passive learning.

“So, the 911 dispatcher will say, ‘Are they breathing?’ then the film pauses, and we ask the audience, ‘Is he breathing yes or no?’ Then we move on to the next part of the film,” Dr. Toft explained.

The film also addresses the emotional and psychological impacts of needing to give CPR to a friend, family member or teammate.

“We are trying to mimic the situation during training and evoke realistic feelings so those intense feelings won’t paralyze anyone who encounters a real cardiac arrest,” Dr. Toft said.

Of particular importance is addressing how to perform CPR on women as some people may be more afraid of giving CPR to a woman, which can hinder the care female victims receive.

The NIH grant will specifically address how to perform CPR on women by addressing barriers to CPR for women such as fear of inappropriate touching and it will also be the first CPR training in the U.S. to feature a female victim.

“Even in virtual reality, women receive CPR less often in public than men do,” Dr. Toft said.

In the end, Dr. Toft hopes to develop an entire system of interactive CPR training films that are adopted nationwide across high schools, sports teams and beyond using different scenarios and new techniques that stick with students longer.

But why, though?

“I’ve always been interested in resuscitation,” Dr. Toft said noting that she witnessed many cardiac arrest victims while serving in the intensive care unit of a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, because people had not received immediate CPR.

“I got so exhausted by that,” she said. “I started doing public training projects, like ‘Start The Heart’ in Louisville, with a fellow cardiologist who was also tired of seeing the same thing and feeling helpless.”

She later met Martin Percy, a British interactive film director, who created interactive CPR training films in the United Kingdom.

“But I wanted to tweak it, make it more competitive, and do hands-on practice,” Dr. Toft said.

She saw sports as an entry point where she could make significant change and impact in a relatively short amount of time. Dr. Toft started offering CPR training to sports fans heading into the KFC Yum! Center stadium in downtown Louisville.

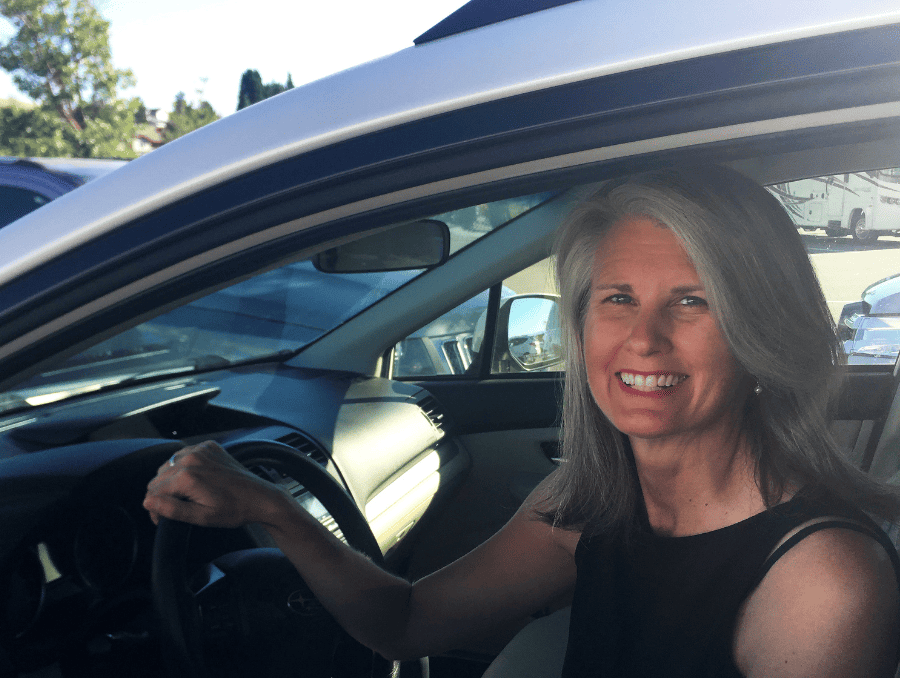

Lorrel Toft, M.D., poses with her Webby Award and Emmy for her CPR training films.

Lorrel Toft, M.D., poses with her Webby Award and Emmy for her CPR training films.In the 10 years since working in that ICU, Toft has continued to iterate ways to present CPR training and has been recognized by other organizations for that work. Her team received a Webby Award for “Cardiac Crash: Monica,” a film that is part of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada’s initiative to increase the chances of survival for all genders in the event of a cardiac arrest. Her research on a novel interactive film to teach CPR in high schools was recently published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. And her original interactive CPR training film “HEART CLASS” received an Emmy in 2020.

“Research is a long game and can make you feel disconnected from the effect you’re having,” she said. “But since I’m always training people on the grant, I see the practical result, and it drives me.”

Next, Toft’s team will begin writing the new films, casting, scripting, recording scenes, editing, implementing and seeking feedback from trainees. She hopes to see nationwide adoption of these videos across high schools, professional athletic teams and beyond.

“It’s been a yearslong journey of seeing an opportunity to address the problem, researching, collaborating, looking at how the laws work and getting to this point to secure the grant and make this game-changing program,” she said.