“I’m over here.”

Taylor Seidler, a graduate student in the Department of Psychology’s Behavior Analysis Program, gently prompts a young boy to turn his gaze in her direction. He locks eyes with her and they both smile as they continue their conversation—something about the game they had just been playing. The boy is three years old, and as they sit on the floor of his play room surrounded by well-organized bins of toys, they look at ease enjoying one another’s company as they play. The only reference to the session serving as treatment is the notebook Seidler quickly scribbles in after each of their interactions.

The young boy has a diagnosis of autism and Seidler is one of a number of tutors providing him 30 hours of treatment a week as part of the University of Nevada, Reno’s Early Childhood Autism Program (ECAP). All of the expected characteristics of a child with autism (such as avoiding eye contact) are almost imperceptible in this young boy as he engages with Seidler on a range of activities geared toward the development of neurotypical requisite behaviors. He has been enrolled in the program for about a year at this point, and he seems in many ways more verbally and socially advanced than the average three-year-old. The program’s co-founder and director, Patrick Ghezzi, describes this treatment as engaging with the behaviors associated with autism, not the diagnosis.

“You really don’t need the noun to treat the child,” Ghezzi said. “Autism is a verb—it’s what kids do too much or too little of. We think of autism as behavior. With that approach, the autism diagnosis becomes far less important than understanding the behavior of the child.”

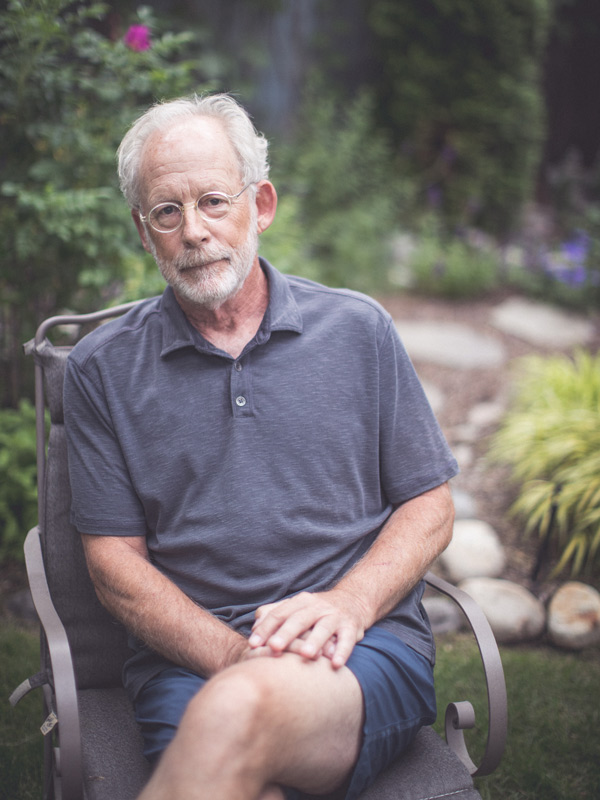

The young boy working with Seidler is one of the program’s many success stories. Started four years after the launch of the Behavior Analysis Program in 1990, the Early Childhood Autism Program has been in service to the community and families in need for 26 years. Now, with Ghezzi’s retirement in June of 2020, the program has been paused as the Department of Psychology and Behavior Analysis Program reorganizes to fill Ghezzi’s very big shoes. If and how the Early Childhood Autism Program will come back and what form it will take is still yet to be known. Its legacy, however, is clear and far-reaching.

Humble beginnings

Ghezzi describes the early years of the Behavior Analysis Program and the development of the Early Childhood Autism Program as “building an airplane as it was flying.” Foundation Professor and developer of the widely-used acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) procedure Steven Hayes, along with his wife and fellow distinguished professor Linda Hayes, launched the Behavior Analysis Program two short years before Ghezzi joined the faculty in 1992. As word of the program spread through the Reno community, a phone call came in from a local family. The parents of a young boy diagnosed with autism reached out with the understanding that “applied behavior analysis” would be the best treatment for their son. There must be some way to help, they implored. With the Behavior Analysis Program still flexible and in its infancy, the small but growing group of faculty jumped into action. Ghezzi, along with the late distinguished professor Sidney Bijou, worked with the family to set up a treatment plan for their young son. Relying heavily on the expertise of Bijou’s former colleague and pioneer in early intervention and autism at the University of California – Los Angeles, Ivar Lovaas, the two professors quickly developed a powerful set of curricula to meet the needs of this child and family and others seeking treatment for young children with autism. While initially, Ghezzi and the other faculty members saw this new initiative as a way to generate funding to support the self-capitalized Behavior Analysis Program, its value immediately surpassed that of financial support.

“It quickly became more than a revenue generator, and I’m talking within days,” Ghezzi said. “You look in the eyes of a parent and you quickly discover this is very important work. You discover you can make a significant, lasting and meaningful difference in the life of a child and family. I started to care more about the kids and families than anything else in my professional life. This really clarified what I cared about and what my values were and still are today.”

The program quickly flourished, taking on more young children and families and becoming a valuable source of experience for graduate and undergraduate students. The program not only helped kids and families in need, but produced valuable research, trained and supervised countless treatment professionals, and helped the Behavior Analysis Program to become the internationally recognized program it is today, regularly receiving high rankings among the most prestigious graduate schools.

As the program’s success gained notoriety, Ghezzi was nominated for the Distinguished Faculty Outreach Award by the late University President Emeritus Joe Crowley in 2011. In his letter, Crowley praises Ghezzi for his “passion, determination, intellect, caring attitude, solid research foundation and, yes, courage.”

“I began to hear from parents, expressing joyful, sometimes tearful, gratitude for what Pat and his staff had done for their children,” Crowley’s letter continues. “Families from across the country have come to the Reno area so their autistic children could take advantage of the Applied Behavior Analytic approach that he has so successfully instituted here.”

With 10 more years of service to the community after this letter was written, the program and Ghezzi’s impact on the autism community is immeasurable.

From diagnosis through treatment

“We’re not trying to fix some assumed pathology that resides somewhere in the brain. We’re trying to help individual children perform to the best of their capabilities and benefit maximally from the services we provide."

Over the past 26 years, the Early Childhood Autism Program has perfected its treatment based on the belief that with regular and consistent reinforcement, children with autism could make significant adjustments to the behaviors associated with their diagnosis. Staheli Meyer, the program’s Associate Director and behavior analysis doctoral candidate under Ghezzi, develops individualized curriculum to do just that. After earning her Bachelor’s Degree in behavior analysis while working as a tutor in the program, Meyer continued on to pursue her Ph.D. and took on case management and her Associate Director role in the program as a graduate student.

“A lot of what the program is designed to do is help with behavioral deficits and put children on a trajectory toward more typical development,” Meyer said. “We’re not trying to fix some assumed pathology that resides somewhere in the brain. We’re trying to help individual children perform to the best of their capabilities and benefit maximally from the services we provide."

These behavioral deficits are commonly rooted in the child’s social experience, often displayed as an unresponsiveness and passivity toward major or minor social cues while, at the same time, showing excessive preoccupation with anything other than social stimulants. While each child’s curriculum is individualized to meet the family’s unique needs and the child’s unique behaviors, this is where treatment begins.

"What you’ll see commonly in children with autism is they can be fairly unresponsive to other people,” Meyer said. “Often times our first set of curriculum is to establish control in the social environment."

Tutors work with children on following verbal instructions such as standing, clapping their hands or turning on and off lights when asked. There are vocal imitation exercises and motor imitation games. Motor imitation, for example, is used to not only teach individual actions, but is meant to help the child to learn from watching others—a pivotal response. The consistency and structure of the program is reinforced in each session.

Surprisingly, another critical aspect of the treatment does not involve the child at all. Ghezzi insists on initial parent training before fading in a team of tutors to work directly with the child. Parent training and child treatment sessions occur in the family’s home—another valuable aspect of the treatment—and eventually the child reaches the goal of 30 hours per week of individualized treatment.

“The first thing we do is meet the parents,” Ghezzi said. “We explore their home routine and discuss their goals. What we commonly see is a family with a child who controls the parents’ every move by tantruming, hitting and screaming for their attention or to escape from something they have asked their child to do or not to do. We see this as accommodating their child’s autistic behavior. We regard it as counterproductive to what we plan to accomplish with their help, which is to eradicate autistic behavior and replace it with more positive and appropriate ways to behave. The result is a family with a better balance, one that puts the parents in control over their own lives and the life of their young child. Once the parents are on board with the utility of this approach, then we begin to fade in a team of tutors.”

Staheli Meyer develops individualized curriculum to meet each child's needs.

Staheli Meyer develops individualized curriculum to meet each child's needs.In the beginning and throughout a child’s service, the treatment team works closely with the parents on developing their own set of skills necessary for maintaining their child’s progress. Because each family is different, treatment and parent training is tailored to meet each family’s individual needs, often adjusted in response to successes or difficulties in different areas. If a parent is struggling when bringing the child along to the grocery store, for example, a tutor will plan a session at the grocery store with the parent. If the child’s behavior at dinner is difficult, a tutor will join the family at a meal. Tailored sessions also reinforce progress. If a child shows improvement verbally, the tutor will focus on developing their language skills even more.

“Treatment spans all the way to more advanced curriculum like being able to have a conversation with a peer in a classroom, being able to talk about how things compare and relate to one another,” Meyer said. “We’re trying to best prepare them for the environments in which they’ll find themselves in the future. If they’re headed to school, we’ll teach them things to help them in that environment—how to raise their hand, play with their friends, that type of thing. It’s a broad curriculum dependent on what each individual child needs.”

The reward of “I don’t need this anymore!”

A child and family are in treatment for two years or more and make incredible progress, often assimilating into more typical social life with relative ease. It is an immeasurable gift to the family and one that, for the treatment team, is incredibly rewarding to give. The tutors are often with the family through some of the most memorable moments in their lives—such as a child saying “momma” for the first time.

“We have many times taught a child to say mom or dad,” Meyer said. “Watching a mother’s eyes tear up when they finally felt they could connect with their child that way—those moments have been especially special. When we get to see the child show emotion towards another person, towards a loved one, that is very rewarding to see.”

When treatment is successful, there are many moments like this. Transitioning a child into school is always a favorite for Meyer.

“Helping a child transfer into school is really exciting,” Meyer said. “You get to watch them go on the playground and make a little friend for the first time. I love that. I’ve also had kids turn to me and say, ‘I don’t need to do this anymore!’ That’s a great moment when I’ve put myself out of work because the kid knows he doesn’t need me and is confident he can do things himself.”

Two short years out of the span of a person’s life may seem negligible, but for these children and families, the two years spent in treatment with the Early Childhood Autism Program can completely change the trajectory of their lives. That first child taken on by Ghezzi and Bijou in 1994 has since graduated from college and lives and works in the area. He went on dates in high school. He made friends. He led an extraordinarily ordinary social life.

“I don’t hear from a lot of parents after they leave the program,” Ghezzi said. “We represent a period of time that they would just as soon forget. But sometimes I do hear from parents, usually out of the blue.”

It might be a card sent years later from a mother thanking Ghezzi and his team for “the gift of recovery for our daughter.” Or the tutors might be sent a photo of the child to tack on the wall.

“One of the things we love the most is when parents send us their kid’s first-day-of-school photos for years after being in the program,” Meyer said. “Those are really special contacts we get to keep having.”

Looking toward the future

As the program shifts to a pause with Ghezzi’s retirement, Meyer has been hard at work transitioning current patients into comparable treatment programs, making sure they experience no gap in care.

“We are in touch with other service providers, many of which employ graduates of our program,” Meyer said. “We thought about each client and matched them with the service we thought would be best.”

As she continues through the doctoral program in behavior analysis, Meyer’s experience with the Early Childhood Autism Program will continue to be a guiding force.

“I really think this program will be missed and I hope that something will come to fruition that will provide a similar service to the community,” Meyer said. “I feel really honored to have gotten this experience to work with Dr. Ghezzi and also the families we’ve worked with. I think I’ve made a big difference in their lives and they’ve made a big difference in my life. I’ve been given a lot of opportunities that not everybody gets, and I am really grateful for that. I feel really prepared, as I think many of my fellow graduate students do, to go out in the community and make an impact.”

As Ghezzi adjusts to life out of the office, he is able to reflect on the past 26 years running the Early Childhood Autism Program.

“The program has had an impact, there is no doubt,” Ghezzi said. “But I share that with the students, like Staheli, and the hundreds of students in this program who have worked in the homes of these kids over the last 26 years. I couldn’t have done it without them, and I am forever grateful to them for showing me my passion in life. This is an amazing group of people who have a love for this work, this field, these kids. I’ve been affected as much by these students as I have been by the kids and parents we serve.”

While the Early Childhood Autism Program may no longer exist as it has for the past 26 years, the lives of the children who received treatment, the students who helped them and the man who started it all have forever been changed. Ghezzi plans to remain involved with the Behavior Analysis Program through his retirement and has offered his support to one of the Department’s newest hires and autism treatment expert, Bethany Contreras, as she transitions into the Department of Psychology.

“We rolled out a really good intensive early intervention program,” Ghezzi said. “But that was because we rolled out a really good Behavior Analysis Program. That is the legacy that time and transition will not diminish.”