Jewish heritage in las Américas

Contemplating, honoring and celebrating Jewish American Heritage Month beyond just the United States

May was proclaimed Jewish American Heritage Month by President George W. Bush in 2006, in part to recognize and celebrate more than 350 years of American Jewish history. It is a designated period of time set aside annually to recognize and honor the achievements of American Jews and their contributions to the fabric of society in the United States. It is also a time to reflect on the historic presence and recent resurgence of virulent antisemitism in this country and elsewhere in the world as a global phenomenon and to stand against it and all manifestations of hate.

In addition, it is an opportunity to think about what “Jewish American” means, or might also mean. Being Jewish encompasses multiple identity components that include religious, ethnic, cultural and linguistic facets that can be varied and quite diverse. Likewise, “American” does not mean the same thing to everyone. Outside of the United States – and more broadly, the English-speaking world – America is understood as the American continent, sometimes referred to in the plural as the Americas; in Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries, América or las/as Américas.

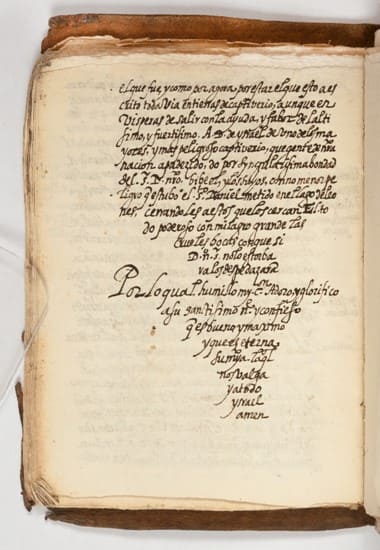

People outside of Latin America typically react with surprise to learn that there are Jewish Latin Americans throughout las Américas who constitute a significant portion of the global Jewish diaspora(s). The encounter with the New World brought many Jews to what would come to be known as the American continent. Many of them were Sephardic converso or criptojudíos (Crypto-Jews) who, following the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain, sought a place far from the reach of the Inquisition. Unfortunately, the Inquisition soon followed them and was established in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of Latin America. One of the most famous Crypto-Jews of the New World was Luis de Carvajal, el Mozo (1567-1596), whose story, and that of his family, is well-preserved in the historical documents of the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico. He was accused of and tried for Judaizing (practicing Judaism) on two occasions. He was later subjected to torture and coerced into revealing the names of over 100 other Judaizers, including his own family members. On Dec. 8, 1596, he was burned at the stake in an auto-da-fé along with his mother Francisca de Carvajal, and his sisters Leonor, Isabel and Catalina. This scene is clearly depicted in Diego Rivera’s mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central” (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park [1946-47]) as one of the key moments in Mexican history. Luis de Carvajal left behind a record of his life and religious practice in 16th century Mexico known simply as Vida (Life) written between 1592 and the time of his death.

The first synagogue in las Américas, Kahal Zur Israel, was established in Recife, Brazil in 1636. By 1642, it had its own rabbi, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, and flourished during the mid-17th century when this portion of Northeastern Brazil was controlled by the Dutch. The original synagogue no longer exists, but there is a museum on the original site. The Mikvé Israel-Emanuel Synagogue in Willemstad, Curaçao was established in the 1650s by Sephardic Jews and is the oldest surviving and continuously operating synagogue in las Américas. It is known locally the Snoa, an abbreviated form of the word esnoga, the Djudeo-espanyol, or Ladino, word for synagogue.

Given this early colonial history, one of the principal misconceptions about Latin American Jewry is that it is comprised primarily of descendants of the early Sephardic Jews. However, the vast majority of Latin American Jews are Ashkenazim (Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe) who arrived in Latin American in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1891, the German-Jewish philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch formed the Jewish Colonization Association and purchased thousands of hectares of land primarily in Argentina (but also in Brazil) with the purpose of resettling persecuted Russian and Eastern European Jews on agricultural colonies. Between 1891 and 1932, more than a dozen colonies were established and thousands of Ashkenazic Jews immigrated to the Promised Land of Argentina. At one point in the early 20th century, Argentina was home to the fifth largest Jewish population in the world. Today, it continues to be home to the largest Jewish population in Latin America, though major communities also exist in Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay and Chile, along with virtually every other country in Latin America. Most countries are home to Sephardic, Ashkenazic and Mizraje (Middle Eastern) Jewish communities. Somewhat unique to Mexico City are its large communities of Halabi (Aleppan) and Shami (Damascene) Jews who emigrated from Syria to Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s.

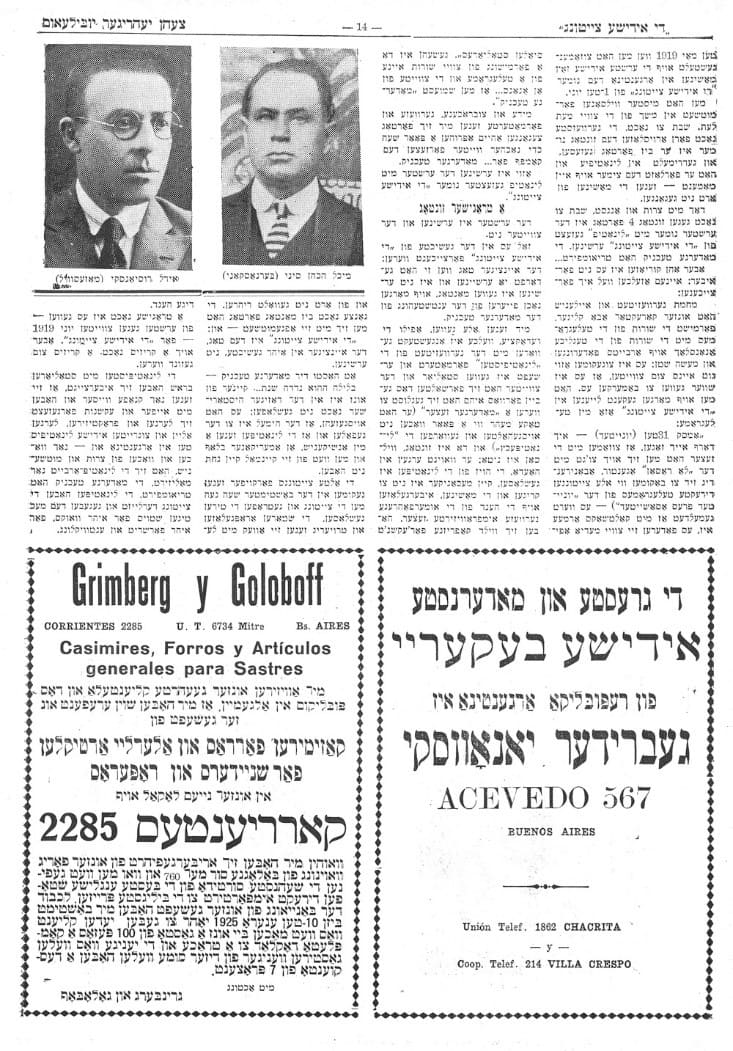

Buenos Aires, much like New York, had a vibrant Jewish component to it with several newspapers in Yiddish and a thriving Yiddish theater scene. The first writers to produce literary accounts of Jewish immigration to Argentina wrote in Yiddish, some later making the transition to Spanish to become major figures of Argentine literature. Yiddish was also prevalent in Mexico, both in the form of newspapers and literature. One of the early and most renown Yiddish poets in Mexico was Isaac (Yizhak) Berliner whose poems first appeared in the Yiddish daily Der Veg, which later published his principal work of poetry in book form under the title Shtot fun Palatsn (1936; Ciudad de palacios). It was a collaborative effort with Diego Rivera, who illustrated the volume with his sketches. Shtot fun Palatsn was translated into English in 1996 as City of Palaces, in an edition that also contains the Rivera drawings.

Literature has traditionally been a major expression of the Jewish Latin American experience and identity. There are approximately 1,000 Jewish authors who have contributed, and continue to contribute, to Latin American literature. The 21st century has seen a flourishing of Jewish Latin American cinema with such films as Esperando al mesías (Waiting for the Messiah; 2000) and Judíos en el espacio (o por qué es diferente esta noche a las demás noches (Jews in Space or Why Is this Night Different from All Other Nights?; 2005) from Argentina; Morirse está en hebreo (My Mexican Shivah; 2007) and Cinco días sin Nora (Nora’s Will; 2008) from Mexico; O ano em que meus pais saíram de férias (The Year My Parents Went on Vacation; 2006), Brazil; and, Mr. Kaplan (2014), Uruguay, based on a novel by Jewish Colombian author Azriel Bibliowicz.

In closing, as we contemplate, honor and celebrate Jewish American Heritage Month, let us explore and think about the variety, diversity and depth of Jewish heritage in a much broader sense throughout las Américas and not just in the United States.

Darrell B. Lockhart, Ph.D. is associate dean of the College of Liberal Arts, professor of Spanish, and co-president of the Latin American Jewish Studies Association.