Foundation Professor of Sociology and social psychologist Markus Kemmelmeier, along with his former Ph.D. student Jesse Acosta, completed research on the evolution of closed-mindedness in the United States.

Their research explores the intersection of political science and social psychology and has been compiled into a paper “The Changing Association between Political Ideology and Closed-Mindedness: Left and Right Have Become More Alike.” It was recently accepted by the Journal of Social and Political Psychology for publication.

Through their research, Kemmelmeier and Acosta posited the question: Have liberals and conservatives always differed in their self-reported closed-mindedness, or have these differences changed over time?

Comparatively speaking, conservatives, as opposed to liberals, worry less about open-mindedness and tend to self-identify as such. Historically, conservative people have described themselves as being less tolerant of uncertainty, less likely to engage in effortful thinking, and less open to changing their beliefs in light of new information. In other words, they self-report a closed-minded orientation.

“People on the right are more focused on conscientiousness,” Kemmelmeier said. “They may be less likely to embrace uncertainty. They stick to traditions and routines.”

Kemmelmeier added that the difference is not large, and whether embracing uncertainty is a good or bad thing is often a matter of the situation. And what some perceive to be narrow-minded might come across to others as principled.

Change is inherently uncertain in its consequence. Because of this, scholars have argued that traditionalism and mainstream ideas appeal to people who are more closed-minded. In the U.S., conservative beliefs have long-standing roots and, at least historically, held more mainstream appeal. By contrast, liberal ideals promote change and the deconstruction of traditional policies and social structures. As such, open-minded people might be more likely to identify with liberal ideals, and closed-minded people more likely to identify with conservative ideals.

“There has long been a discussion as to whether people who gravitate towards certain ideologies have a certain mindset or cognitive makeup,” Kemmelmeier said.

Several studies confirm a tendency for conservatives to self-report greater levels of closed-mindedness compared to liberals. What is less understood is whether this difference in self-rating is subject to change.

Through a meta-analysis, a specific type of statistical analysis that combines the results of many different scientific studies, Kemmelmeier and Acosta tested whether the closed-mindedness of these two distinct groups has increased or decreased over time. They used data obtained over the course of 71 years that assessed the correlation between political conservatism-liberalism and various measures of closed-mindedness.

Their findings confirmed that, in the United States, conservatives generally score higher on self-reported closed-mindedness compared to their liberal counterparts. However, as Kemmelmeier explains, the size of this difference has changed significantly from 1948 to 2019.

“What we found was that in the late 1940s, there was a relatively more pronounced correlation between people who described themselves as being more conservative also identified themselves as being more closed-minded,” said Kemmelmeier. “Over time, however, that correlation becomes smaller and smaller, and today it is less than one-percent of the entire variation.”

An argument that fascist ideology was associated with cognitive rigidity and a lack of tolerance of ambiguity gained traction in the mid-20th century after World War II, following the Nazi regime's rise to power and subsequent failure. Since this period, Kemmelmeier and Acosta’s work suggests that the two dominant ideological groups have undergone considerable change.

The results of Kemmelmeier and Acosta’s research indicates that liberals and conservatives have become more similar in their self-described closed-mindedness over time, especially in the U.S. However, it does not indicate if the closing of this gap is because liberals have become more closed-minded, if conservatives have become more open-minded, or if both are occurring simultaneously.

Their findings also cannot explain why this change has occurred. Kemmelmeier and Acosta suggest that the shrinking differences and preferences between liberals and conservatives might reflect a changing political environment. Specifically, political messages might have shifted such that many liberal values have become more widely discussed and accepted, and conservative values might not represent the source of tradition and certainty that they once did.

“What this really means is that there is less of a difference between conservatives and liberals today than ever before,” says Kemmelmeier.

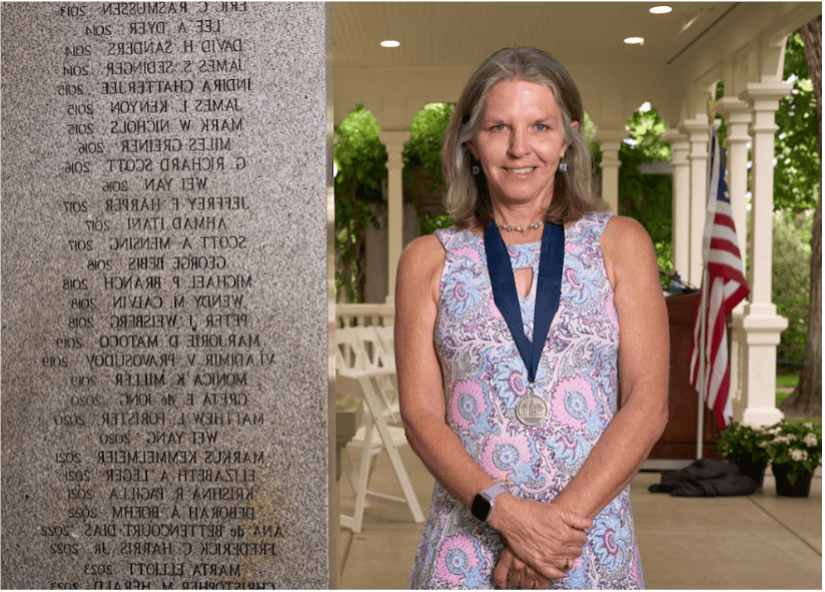

Since 1998, Kemmelmeier has been researching political psychology. For 21 years, Kemmelmeier has taught at the University and has been the director of the interdisciplinary social psychology Ph.D. program for the last seven years. He was recently named the incoming Vice Provost Graduate Education/Dean of the Graduate School. Jesse Acosta recently received his Ph.D. in social psychology and accepted a position at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

“Political psychology is a very active research field,” Kemmelmeier said.