Neuroscience research has revealed evidence supporting the use of transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) to improve visual working memory in older adults. Recently published in the journal Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, the University of Nevada, Reno research adds to the list of scientific findings that are connecting the use of targeted, low-intensity current delivered by electrodes to improve an aspect of cognitive performance.

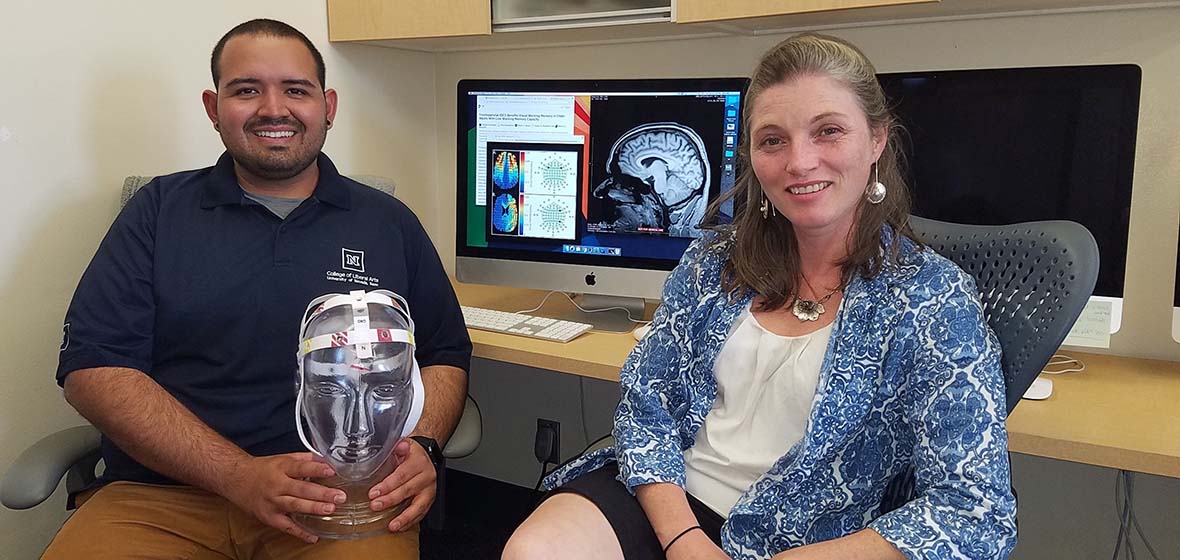

"The big picture was that we were able to help those with low working memory capacities by restoring a more youthful pattern of brain activity," said Hector Arciniega, first author on the study, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Nevada, Reno's Integrative Neuroscience program and an affiliate with Cognitive and Brain Sciences program in the Department of Psychology.

Working memory is a fundamental component of almost every cognitive task. Unfortunately, it is subject to age-related decline beginning in our 20s.

"As we get older, we start noticing it is harder to get hold of information, keep it and use it," said Marian Berryhill, a neuroscientist at the University, lead researcher on the study and Arciniega's faculty mentor.

"It gets people where they live," Berryhill said of the phenomenon that often initially presents as misplacing keys, standing at the refrigerator and not remembering why, losing a train of thought, or starting the car and not remembering the destination.

The brain responds to electricity and, said Berryhill, neurons in the brain are like batteries. Stimulating neurons and making them a little more reactive boosts their performance.

The study involved healthy, older adults (65 years or older), as well as younger adults for comparative purposes. During stimulation, participants performed a visual long-term memory control task and a visual working memory task. The stimulation or tDCS had no effect on the long-term memory task, however older participants showed a working memory benefit. And, this pattern was more robust in older adults with low working memory capacity.

"It gives us a better understanding of mechanisms and can help direct further research," Arciniega said of the findings.

Noting that stimulation "doesn't work in everyone in the same way," Berryhill envisions continued research to explore in whom and when it works best, as well as why it works.

"Medicine is moving to more customized approaches to treatment, and this could potentially be part of future, tailored regimens," she said.

In addition to Arciniega and Berryhill, the project involved University alumni Filiz Gözenman (Ph.D. 2015) at Yaşar University in Turkey and Kevin Jones (PhD 2014) and Jaclyn Stephens (Ph.D. 2015) at Colorado State University. The published study, "Frontoparietal tDCS Benefits Visual Working Memory in Older Adults with Low Working Memory Capacity," is available on the Frontiers website.

Arciniega earned his bachelor's degree in neuroscience at the University of Nevada, Reno and has worked in Berryhill's lab since his days as an undergraduate student. The busy 27-year-old also serves as legal guardian to his 17-year-old cousin. Currently, he is supported by grant funding from the National Science Foundation, with prior support from the National Institutes of Health and the University's Sanford Center for Aging, Graduate Student Association and Department of Psychology. On track to complete his Ph.D. in fall 2019, Arciniega hopes to continue conducting research to explore the intersection of aging, attention, working memory and cognitive improvement.

Donations are encouraged to support graduate student scholarships to study age-related cognitive changes. For more information or to give to the Department of Psychology in the College of Liberal Arts, contact Julie Mathews, director of development, at juliem@unr.edu or 775-784-6873.