NevadaToday

The war on cyberspace Hackers, cybercrime and how pirate history is influencing the future of cybersecurity

The war on cyberspace

You wouldn’t leave your wallet on the table at a coffee shop for anyone to access, so why would you leave your computer or phone unlocked and vulnerable? University of Nevada, Reno cybersecurity expert Christopher Church posed this real-life connection to help people understand cyberspace isn’t wholly separate from physical space.

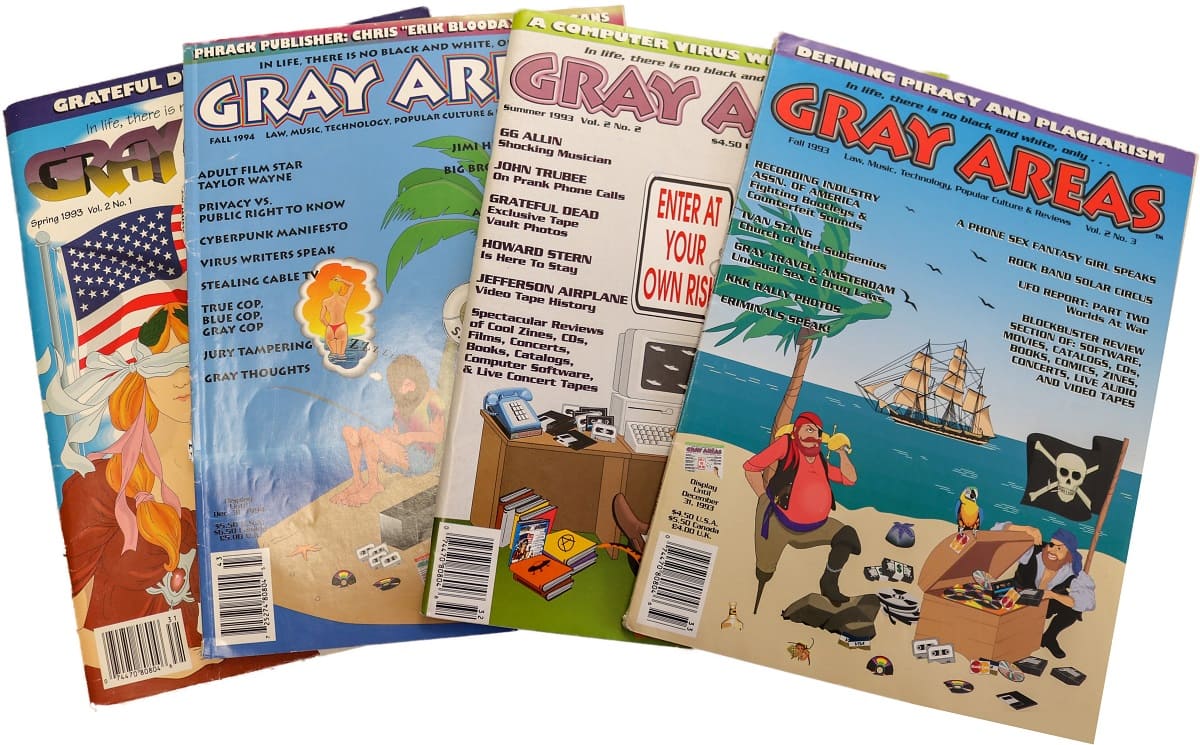

While the technologies have changed over time in how we protect our personal information and secure our valuables, the methods criminals use to break in bear some striking resemblances to the high seas crime of yesteryear. From maritime pirates scavenging for treasure to today’s hackers scouring the internet for weaknesses to steal data, piracy is alive and well, and the war isn’t ending soon.

The physical aspects of cybersecurity

“The world’s trade is migrating from the physical space of the high seas to virtual networks,” said Church, an associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts and a faculty member of the Cybersecurity Center on campus. He also teaches a course as part of the cybersecurity minor called Pirates and Hackers. He emphasizes that while technology has driven the history of cybercrime, it’s also influenced by social, cultural and economic impacts. “What’s going on in cyberspace is not determined by the technology – it’s influenced by tech, but that didn’t start it.” Cybercrime, Church says, is not just a technological problem but also a social one.

Looking at centuries past, humans have always desired more – more sugar, more textiles, more slaves, more money. Goods have always been traded, stolen and sold. Today, the same desires still exist, but the goods have changed some, the methods used to steal them have been modernized and, in many cases, the stakes have been raised.

In Ukraine in 2015, the electrical grid was hacked in the middle of winter. The grid’s physical infrastructure was overloaded. It went down. People lost electricity and heat, and deaths occurred because of the extreme cold. A crime committed virtually took a hefty physical toll.

"What’s going on in cyberspace is not determined by the technology."

In the United States, with proof of international election interference taking place across digital platforms and worry about fraudulent results, cybersecurity often makes headlines, particularly when the presidency is up for the vote.

In these cases, it’s easy to trust that the good side will simply win out with better technology than the bad guys, but the arms race between law and order and the criminal element is a tale as old as time. “If we only focus on it as a technological issue, then we won’t be able to solve it,” Church said.

The history of pirates

Though cyberspace is relatively new, what drives the crime within it has much deeper roots. Church argues that to understand hacker culture, you should look at early modern protests against the growth of trade. There are many parallels in early modern piracy to today’s hackers. Like the priates of yore, they’re often people who feel marginalized in society and left behind in a rapidly changing economy. Pirates used to map trade networks and attack vulnerabilities in the route – hackers do this in cyberspace.

Church said people typically think of pirates as raising their flags on their ships to set sail on the high seas and have dramatic battles on the hunt to find buried treasure chests filled with gold and jewels. “Most of the time that’s not what happened. With the swashbucklers and buccaneers – there was as much conflict and battles on land as there was at sea. They identified the weak points in travel. They were hacking a network in the same mental framework as someone who’s trying to get illegal access to something online today.”

In the early modern period, maritime trade traveled through the same circular networks we have now, and the pirates continually tried to hack those networks. Church, who is writing a book on the topic, said you can’t have piracy without trade, so you need to follow the trade networks to find the pirates. Since the early modern period, trade networks have increasingly become transatlantic and even global. Church said the largest transformation in the world’s trade networks took place between the 15 th and 18 th centuries. “This is where most of the world’s piracy comes from.”

"They were hacking a network in the same mental framework as someone who’s trying to get illegal access to something online today."

As the world moved from the late 19 th century to the present, the trade transformation has become more and more virtual, starting with telegraphs, moving to telephones and eventually to fiber optics and cloud computing. At one point in history, pirates moved textiles, sugar and slaves and held them for ransom – similarly today, hackers will lock down a computer – or an electrical grid – for ransom money. Church said it’s not accidental that virtual data is now one of the most profitable goods. “While the players have changed, the game has structurally remained the same.”

In the early 2000s Somalian pirates, who initially called themselves the Volunteer Somali Coastguard, hijacked international fishing vessels for disrupting the local trade networks. What started as pushback against globalization, gradually lost its high-minded ideals. Somalian pirates found their tactics were successful and quite profitable and continued capturing large transport vessels purely out of financial gain. If you remove the technology, Church says, what’s left is human behavior.

One of the biggest economic ties between historical piracy to the present-day hacker is that piracy is profoundly disruptive. In the earlier periods, piracy was often used to the benefit of the state – or rather to the detriment of a given state’s enemies. Queen Elizabeth I hired pirates to disrupt Spanish trade. Church said the shift in piracy becoming a general economic threat (as opposed to a targeted one) happened at the turn of the 18 th century, when the trade with the New World focused on plantation slavery and sugar. When the pirates started working for the highest bidder and stopped calling any one nation home, the powers that be ran a massive propaganda campaign against piracy.

Church noted a similar process starting to take place today with cybercrime and hacking. Hackers were once seen as helping the little guy – the only opposition to large corporations and monopolies. Now, people are starting to see hackers as enemies of society. Church said the tipping point will come at some point in the future because of massive losses to the world’s economy. Although, he said it’s too early to tell if it will end as a revolution against corporate monopolies or as a backlash against public hackers. “Historians are loath to make projections.”

By understanding how piracy has progressed and evolved since the 15 th century and looking at how it’s changing today, it’s possible to see patterns emerge, and while we can’t say for certain just how things will play out, it’s undeniable that they’re escalating, growing in complexity right alongside our global trade networks.

“In the cyber world, if we just treat the economic and technical side of security and don’t look at the social side or bring in the political and cultural side, then we’re only addressing one small piece of cybercrime,” Church said.

Modern day technology and hacking

Church points out that if you were to look at a map of fiber optic lines today and compare that to maritime trade routes and the railroads, the two look eerily similar. Data is travelling the same routes, something end users don’t often consider when logging into a coffee shop’s network. “Wi-Fi invites this ‘in the cloud’ feeling – but there’s a physical there that evolved with maritime trade,” Church said.

“It’s not insignificant that the parties in Europe fighting for net neutrality today call themselves ‘pirate parties.’ They’re pulling on what they see as a counterculture, as to what existed in the past,” Church said.

Within this countercultural movement, as with the noble-minded pirates of days past, is a hint of altruism, a belief that piracy and hacking serve a common good. Church says our world thrives on using what someone else created and making it better. Getting access to those things someone else created, especially when they’re kept under lock and key, might involve less than strictly legal tactics.

"It’s not insignificant that the parties in Europe fighting for net neutrality today call themselves ‘pirate parties.’"

The hacker community wanted to draw a distinction between criminal activity and “legitimate” hacking. To that end, the hacker ethics were created. They state that authority isn’t to be trusted, that all bureaucracies are flawed systems, that all data should be free and accessible to all because without that it is impossible to repair or rethink and reinvent these systems. The list goes on, and notably, every ethic and principle is a kind of altruism, an emphasis on world improvement.

To hack a system is to make it do that which it wasn’t intended to do, to find workarounds. Church said hacking is merely an activity, not good or bad on its face. But systems generally don’t appreciate being hacked – or at least their creators don’t. Hacking is and has been maligned. The line between strictly criminal behavior and that which is rooted in the hacker ethic is blurry at best.

“Ambiguity is deeply embedded in pirate culture,” Church said. To measure whether the hacking is unethical, you need to analyze its effects.

Surviving the war

Rather than the imperial trade routes of yore, today’s pirates disrupt networks – and on the shoulders of today’s networks rest the global economy, basic utilities and national security. Innocent people died when pirates used cannons to “hack” trade routes. The weapons of cyber pirates are more insidious.

A port sniffer search engine, for example, is a relatively new piece of technology that finds all the routers in a localized area and tells a hacker which systems a default password of “admin,” the equivalent of leaving that wallet unguarded on the coffee shop table.

Church demonstrates in his classes how critical infrastructure, including water control systems and other utilities, are often exposed on the internet to cybersecurity breaches. A lot of equipment used in the last couple of decades sits on networks that were never designed to be on the open internet. Now that they’re plugged into routers, the antiquated systems are sitting ducks for the morally ambiguous hacker.

Through his research, Church analyzed how society’s outcasts continue to respond to the advancements and globalization of today’s economy, mostly negatively. He sees the importance of investing in better technology and smarter, safer and stronger systems – but he also sees that this won’t be enough. “If we’re going to try to stop it,” Church said, “building better locks isn’t going to do it. We need to study the past.”