NevadaToday

All is well at the Student Health Center After 118 years, the student-funded facility remains a vital resource providing comprehensive care to record numbers of students.

All is well at the Student Health Center

As a graduate student attending the University of Nevada, Reno in the late 90s, having relocated from across the country to complete my education, the Student Health Center was where I first sought out health care in this new city.

Now, returning for the first time more than 20 years later, I feel something akin to nostalgia. Despite its recent remodel and high-tech features, this place is familiar and comforting, an important part of my early adulthood that helped Reno feel like home.

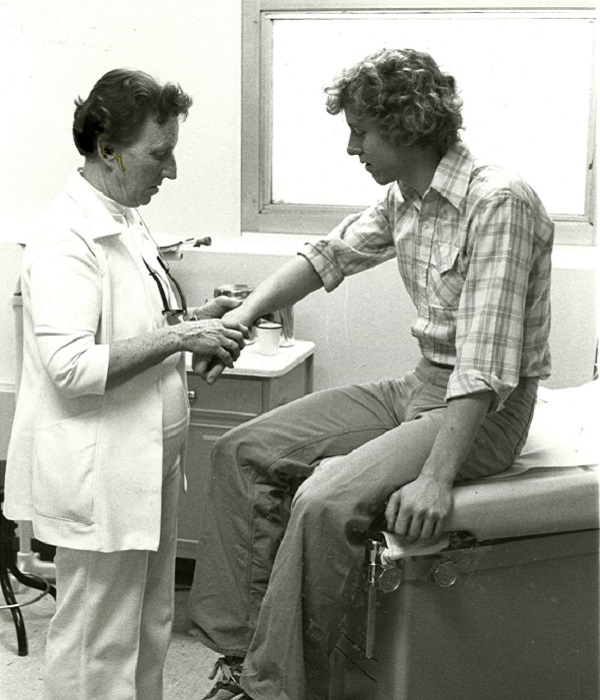

The Student Health Center (SHC), created entirely for the University’s student body, has been the site of some of the earliest and most transformative health care moments in students’ lives. For countless students, this primary care facility has been home to their first independent encounters with health care practitioners, or perhaps where they faced their first serious or adult medical conditions, all on their own.

As students have changed over the course of the last century, the center has also evolved in remarkable ways to meet their needs.

In order to complete the project, the Department worked to design a strategy for how they would go about digitizing the records. They met with the Recorder’s Office team and presented their plan. With the Recorder’s approval, the Libraries team prepared for the arrival of materials.

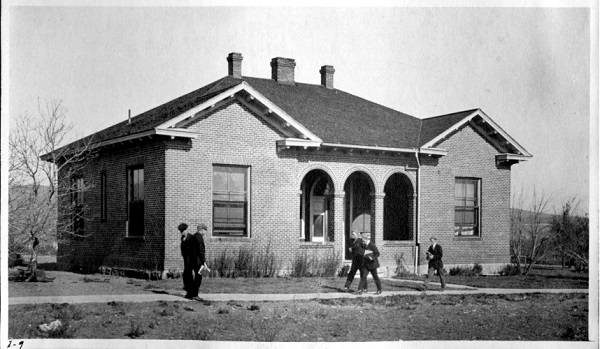

A medical history

Established just prior to 1902 with a Nevada Legislature appropriation of $3,500, the SHC began as an inpatient hospital to house and care for sick students. Comprised of two wards (one male, one female), each accommodating up to 10 students, it began as a standalone facility east of Lincoln Hall and operated purely as an inpatient hospital. In 1961, it was torn down to make way for The Noble H. Getchell Library (where the Pennington Student Achievement Center now sits) and relocated to the first floor of the brand-new Juniper Hall, which opened in 1962. At this time, University leaders opted to make the SHC a more comprehensive outpatient clinic, and it remained in Juniper Hall for the next three decades.

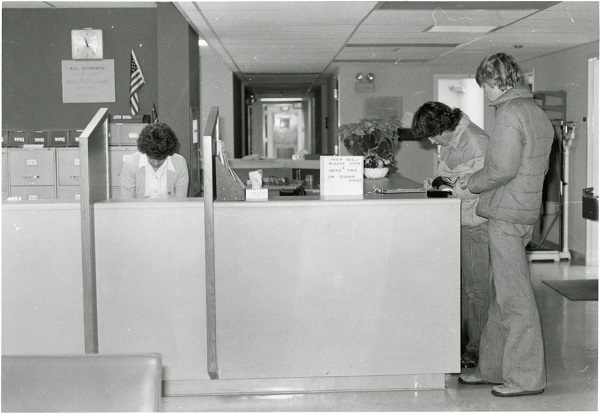

Julee DeMello ’94 (business) came to work at the SHC in 1990 as a freshman to perform light clerical work. She remembers the awkward layout of the Juniper Hall facility, its entrance located directly in front of Manzanita Lake.

“You’d sometimes have to fight the geese to get into the building,” she laughs, adding that the yellow shag carpeting and a physician who smoked inside his office were other memorable features. “It was a little like a dungeon. There weren’t any windows, and the entry stairs came right into the waiting room.” The center’s health care services were still limited at the time, not yet the comprehensive center it would eventually become. This is consistent with how SHC Medical Director Cheryl Hug-English, M.D. ’82, remembers it being when she joined the center’s staff.

“It was just myself and one other physician. I remember when I started, there were no women’s health services, no birth control prescribed,” Hug-English recalls. “We didn’t have a laboratory, and we did not have any x-ray facilities.” When the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine took the SHC under its wing in 1988, Dr. Hug-English was approached about heading up the SHC and developing it into a more comprehensive health care center. “I have to say, I fell in love with it from the first day, really, and I’ve been here ever since,” she says fondly.

Hug-English, who had practiced women’s health care at UNR Med’s Family Medicine Center over the previous year, made developing a women’s health program that could provide services such as pregnancy testing and annual pap screenings a top priority for the SHC.

In 1993, thanks to a donation from the Nell J. Redfield Foundation, the SHC moved out of Juniper Hall and into its current home, a new building at the north end of campus.

The center’s services and salaries are funded through a health fee paid by University of Nevada, Reno students during registration. The Board of Regents, University administrators and the Associated Students of the University of Nevada (ASUN) made the fee mandatory in 1995 for all students taking six or more credits per semester. The fee, which is currently $93 per semester, covers most health care services provided at the SHC.

In 1993, thanks to a donation from the Nell J. Redfield Foundation, the SHC moved out of Juniper Hall and into its current home, a new building at the north end of campus.

The center’s services and salaries are funded through a health fee paid by University of Nevada, Reno students during registration. The Board of Regents, University administrators and the Associated Students of the University of Nevada (ASUN) made the fee mandatory in 1995 for all students taking six or more credits per semester. The fee, which is currently $93 per semester, covers most health care services provided at the SHC.

“When we moved into this building, we were able to expand and increase our services,” explains Hug-English. “Throughout the years, we’ve really evolved into a comprehensive family medicine clinic that provides a real variety of services for students.”

Comprehensive new offerings

The center’s services evolved beyond the general treatment of illnesses and injuries to a true primary care practice with a growing array of specialized care services, including sexual health, sports medicine, psychiatric care, dermatology, nutrition counseling, vaccination clinics, sexually transmitted disease (STD) testing, eating disorder treatment, health education and more.

When Carol Scott, M.D. ’91, joined the SHC in 1994 as its assistant director, she brought experience in family medicine, as well as qualifications in sports medicine and adolescent medicine to the position. Almost immediately, Dr. Scott set about developing a primary care sports medicine fellowship, which was formally established in 2007 with Scott as its director. Although the SHC had never before been a training ground for UNR Med residents, it now would do so in a limited capacity, training residents to provide sports medicine services and treat injured athletes.

“We provided game coverage, did the emergency planning and preparation, traveled with the football and basketball teams, so the fellows really got a full year of just learning about the different sports — from rifle team to swimming, golf, football — the whole nine yards,” Scott says.

The fellowship program has flourished, with three sports medicine physicians and two fellows per year. Scott is no longer its director, as her role as team physician for Nevada Athletics and her duties at the SHC keep her quite busy, a vast difference from 1994.

“I remember when I started, sometimes I’d actually sit around a little bit and wait for patients to come in,” Scott remembers. “Now, we’re busy all the time.”

In fact, as the center’s services have increased, so have its patient numbers, says DeMello, who stayed on with the Student Health Center upon graduating, first as its business manager and eventually in her current role as clinical operations manager. According to her data, in 2018, the center saw a record number of patient visits, at 30,400. More than half the student body has visited the center at least once.

This may be due in part to physicians’ and staff members’ efforts to increase the SHC’s visibility and awareness about its clinical services and the value offered with the health fee.

“There are so many things included in the $93 health fee. Occasionally people don’t want to pay it, and I think some of the resistance comes from not understanding what the fee is actually for,” DeMello says, explaining their ongoing efforts to reach students on campus and share information about the valuable range of available services.

Even the roughly half of students who have not visited the center have benefited from the work it does, DeMello says. “You never know if the people next to you have received care here, and that has kept you or your roommate healthy. To have unlimited access to five months of primary care visits for $93 is pretty spectacular. Plus, we offer a registered dietitian, free health education, free STD testing, which are hugely popular. It all makes for a healthier campus.”

To spread the word around campus about the SHC’s clinical services, the center participates in student orientations, holds flu shot clinics and attends school events. In 2018 alone, the center participated in 19 new student orientations, provided basic health training to more than 120 resident assistants, performed more than 520 free STD tests and gave more than 2,500 free flu shots.

Additionally, a team of 26 university students have been trained as peer health educators to help with health education efforts across campus and perform minimal health care services. “We find that it’s sometimes a little easier to talk to a peer than an adult,” DeMello says.

Peer health educators participate in student engagement events, free STD testing events and flu shot clinics. They also occasionally visit classrooms to share information about the SHC or educate students about various health-related topics.

Shiny new digs

DeMello proudly walks me through the new and improved SHC, which underwent a significant renovation in 2015. She steps me into the lab and gestures around the room.

“One of the great things that came out of our remodel was the lab,” she explains. “We now have two designated areas with some moderate privacy. Lab techs can actually draw blood and bring in specimens. Doctors can then view them through a microscope, and everything gets entered into the computer system. We’re interfaced with Quest, so when results come back, they go right into the patient’s electronic medical record. So things are happening a lot faster than they used to, and there’s a lot less room for error.”

In fact, the lab — which can process certain tests on site such as those for strep and mononucleosis, as well as pregnancy tests and urine samples — is just one of the many improvements to come out of the renovation, funded by another generous Redfield Foundation gift. With an additional 1,900 square feet, the Student Health Center grew to include six new exam rooms, four new offices, a second waiting room for appointments, a larger and more welcoming reception area, a new conference room and a kitchen.

With the new vaccine refrigerator, dubbed “Hal” because of its sophisticated alarm system, the SHC can offer many different immunizations. Multiple rooms serve as shared quarters for psychiatric care. Another room has been designated for minor surgical procedures. And an orthopedic treatment room features musculoskeletal ultrasounds and an assortment of orthopedic devices.

It’s not just the facility that’s grown and been modernized. DeMello says that student demand has changed the way SHC does business. The hours have been extended to 6 p.m. Monday through Thursday, to serve working students, and a same-day appointment model enables students to be seen almost immediately.

“I’m proud of the fact that we’ve been able to build such a great resource for students, who often are seeking health care for the first time,” says Hug-English. “We’ve tried to be a welcoming environment for students and make it as easy as we can for them. It’s kind of a one-stop-shopping experience with respect to health care.”

Today’s Student

A far cry from the infirmary it was originally designed to be, today’s SHC treats students for any number of diagnoses. In fact, De- Mello says that in 2018, the center made more than 38,000 diagnoses.

Although a good many of them are the to-be-expected colds, flus, respiratory illnesses or STDs common among young adults, Hug-English says the variety of diagnoses is more robust than one might expect.

“We really see the full range of diagnoses,” Hug-English says. “I think one thing that has changed is the different age groups that are now coming to college. Of course, we still see the traditional 18- to 24-year-olds, but we’re also seeing some older, more nontraditional students, and with that comes different diagnoses. We certainly also see cancers in all ages, diabetes, cardiac issues and multiple sclerosis.”

Birth control and HIV prevention counseling have increased, as well.

“You know, any diagnosis can walk in on any day,” says Scott. “Last week, there was a day I saw a patient about an unplanned pregnancy, then someone came in with onset of seizures and then a wrist fracture after that. It’s not just colds and STDs.”

SHC physicians will work with students’ hometown physicians or can refer students to specialists nearby.

Hug-English adds that the SHC also takes the lead in stopping the spread of infectious diseases, such as when, in 2018, a University student was diagnosed with measles.

“We took the lead in making sure the campus was safe and coordinated management with the Washoe District Health Department. We’re also involved with the University's emergency response team,” she says. “So I think we have a unique opportunity to serve not only individual students, but also to serve the campus as a whole.”

Scott points out that vaping is a newer issue about which the SHC physicians are counseling more students, and since the legalization of recreational marijuana last year, more patients have come in complaining of bad side effects.

Hug-English has also seen an increase in the number of male patients. “The willingness of more men to seek out care and be open about their own health issues has changed, in a good way, with more men being willing to come in and be seen,” she says.

But if both doctors had to pick one area that has really changed over time and seen significant growth, it would be the number and severity of mental health issues.

“There certainly is a lot of depression and anxiety, and we pay careful attention to issues of potential suicide, which is one of our biggest concerns when we’re dealing with a mental health issue,” says Scott.

Hug-English suspects some factors contributing to the rise in mental health visits include financial or food insecurity, the rise of social media, a greater acknowledgment of the complexities of gender identity and society’s increased acceptance on discussing mental health.

Hug-English is also a certified eating disorders specialist. At the SHC, students with eating disorders are evaluated medically, receive nutritional care from a registered dietitian and receive psychological support from the University’s Counseling Center or SHC psychiatrists. This team approach allows for greater success with recovery.

Looking ahead

As to what’s next, Hug-English sees the SHC continuing to adapt, especially in the face of a growing and diverse student population that will place further demand on constraints of space and staffing. She is also concerned about meeting the growing demand for mental health services.

“We want to continue to evolve with the needs of students with respect to inclusion, diversity and cultural changes,” Hug-English says. “The student body is changing, and we have a lot of international students coming to campus.”

She says her “wish list” includes the capability to offer traveling clinics to serve students off campus.

“We value patient feedback and conduct yearly patient satisfaction surveys so we can better understand the needs of our students,” DeMello says, adding that the SHC has been exploring how it might potentially add an online scheduling model in the future, to enhance convenience.

For all three women, the continual evolution and diversity of students and diagnoses has made it enjoyable to work at the SHC all these years.

“I love the opportunity to work with students,” says Hug-English. “Students are incredibly passionate, and they want to be involved in their health care decisions. They are eager to learn, and they continue to challenge us to grow and learn. I have found it to be a really energetic environment to continue to practice in. So I’m grateful for that opportunity.”