Standard 4. Content, activities and interaction

Jump to:

- 4.0: Each module includes an overview or review page, including a checklist or summary of activities that students will need to complete, indicating those that are practice-only, graded, submitted, not submitted, etc.

- 4.1: Course materials comply with copyright laws or fall within the guidelines for fair use

- 4.2: Materials, activities, and assessments promote the achievement and alignment of course-wide objectives/SLOs

- 4.3: Adequate time is provided for students to complete and submit activities, and time requirements are clearly communicated

- 4.4: Frequent instructor communication is present throughout the course, enabling ample opportunities for students to engage with instructors

- 4.5: Expectations for student interaction are clearly stated, including netiquette, grade weighting, models/examples, and timing and frequency of student contributions or participation

- 4.6: Course offers opportunities for student-to-student interaction and constructive collaboration

4.0: Each module includes an overview or review page, including a checklist or summary of activities that students will need to complete, indicating those that are practice-only, graded, submitted, not submitted, etc.

Providing a rough outline, road map, activities list, and/or overview is a best practice in online course design because this helps students navigate both the course site and instructor expectations. Courses without regular assessment, direction, skill-checks, and or measurement can reduce student competency, engagement, and motivation.

Students benefit from knowing what they are about to learn, as well as the scope of work and time commitment expected from them. Therefore, each module should include information that enables students to become self-directed, provides them helpful information regarding what to expect in the module, and assuages any anxiety of starting a new module.

Module overview pages should provide advance information on what content, interaction, and assessment will take place within specific time periods, as well as an estimate of how much time students will spend on course work each week. In essence, this overview introduces the module’s content and sets your students up with an idea of what will be covered, what tasks they should complete, and which learning outcomes the module helps meet. The module overview may include any of the following:

- Brief Overview / Introduction to Module Content

- Module-level Learning Outcomes

- Activities List / Summary of Tasks

- Due Date Reminders / Heads Up on Assignments

- Time on Task Estimates

Module road maps / activities lists / reading and viewing assignments could be their own page in the module, or within the module overview. Importantly, any graded material or time-sensitive / out of the norm for due dates/times should be communicated in this section of the module so students can plan appropriately.

- Record welcome videos:

- Screen-capture your syllabus, walking your students through it and providing explanations as you would on the first day of a face-to-face class.

- Create brief welcome videos for each module where you’re speaking comfortably and in a friendly tone, facing the camera.

- Use learner-centered language and address what they will experience and should expect to accomplish.

- Provide an estimate of the expected time-on-task amounts, if possible.

- Address a single student by using the second person singular (e.g., “You will learn…”).

- Anticipate the questions students might ask about the course and module (e.g., access, navigation, learning materials, due dates, etc.) and address them within the overviews.

- Provide reminders of upcoming due dates, quick explanations of the purpose of assignments, lists of key concepts that will be covered, and/or a brief reading guide.

Online module overviews and activities lists / road maps / reading and viewing assignment pages can help support Regular and Substantive Interaction (RSI) by including specific explanations, instructions, and details on how, when, where, and by whom online course communications, interactions, discussions, etc. will take place, along with directing students to ask questions and interact with the instructor regarding such topics.

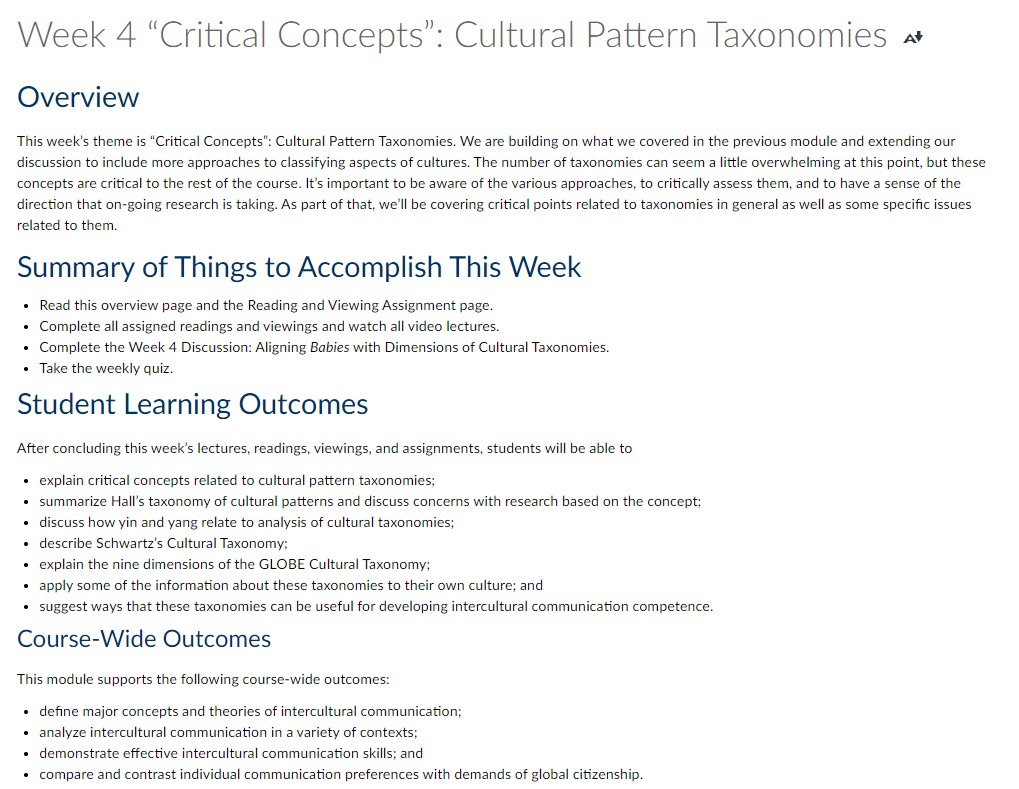

Sample Overview page provided by Communication Studies Instructor Kelly Tait:

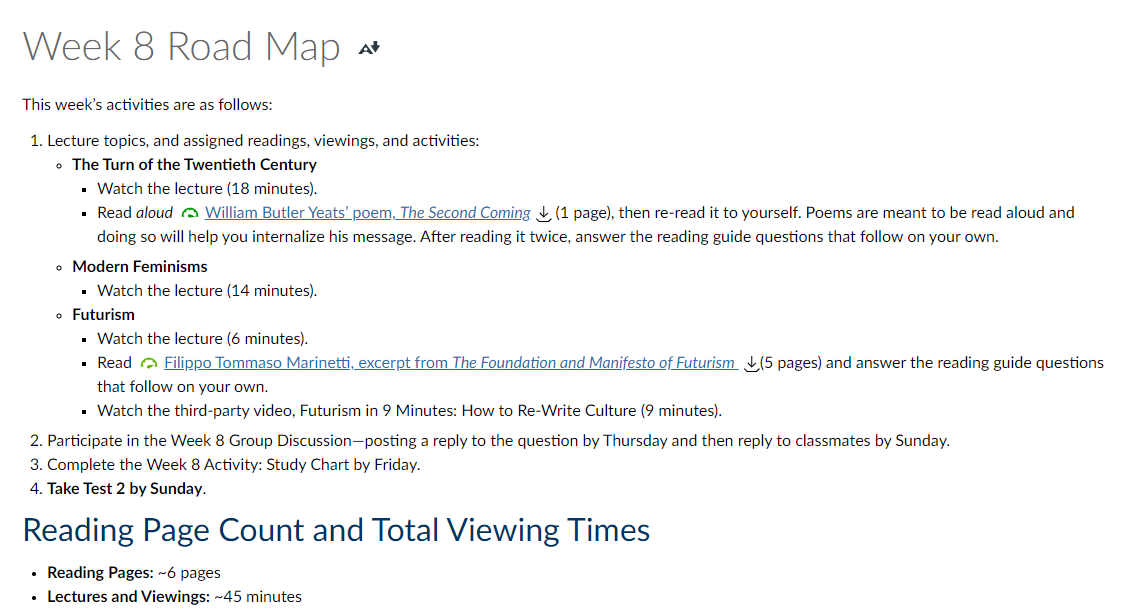

Sample Road Map page provided by Core Humanities Instructor Angela Chase:

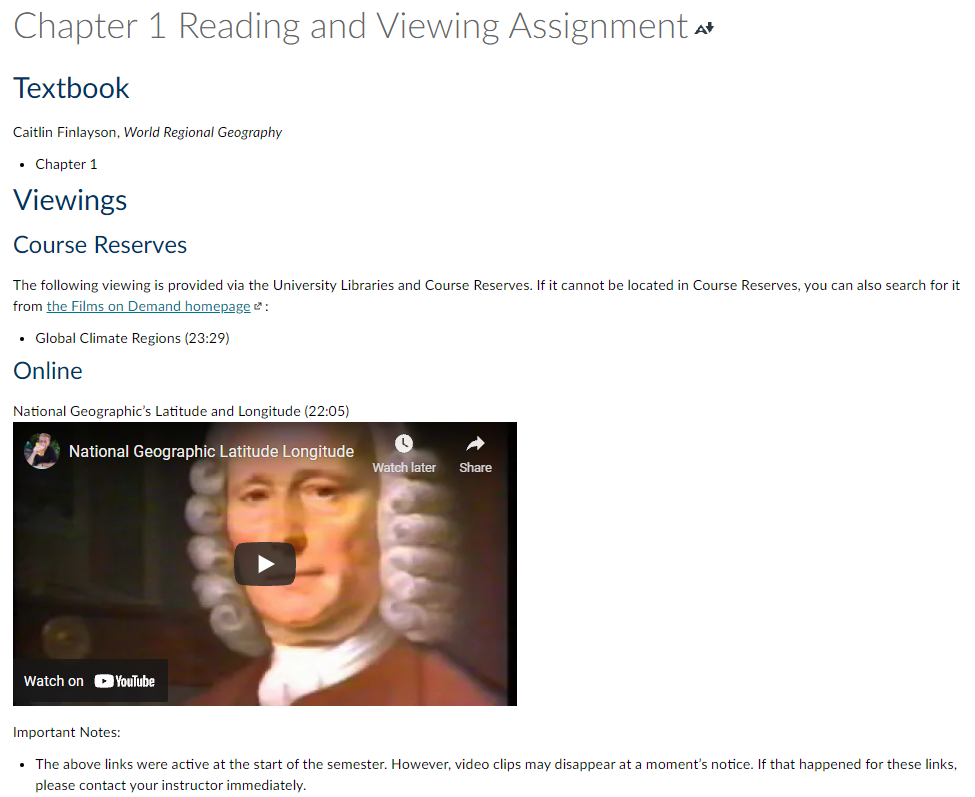

Sample Reading and Viewing Assignment page provided by Geography Instructor Christine Johnson:

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, P.A. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Allyn & Bacon.

Gamrat, C. (2020, February 6). Inclusive Teaching and Course Design. EDUCAUSE Review.

Kelly, R. (2009, September 15). A Modular Course Design Benefits Online Instructor and Students. Faculty Focus.

Quality Matters. (2018). Higher Education Rubric Workbook: Standards for Course Design (6th ed.) MarylandOnline, Inc.

Schwartz, S. (2021, August 18). Weekly Guidelines for Students in Asynchronous Online Classes. Faculty Focus.

Vai, M., & Sosulski, K. (2016). Essentials of Online Course Design: A Standards Based Guide. Routledge.

4.1: Course materials comply with copyright laws or fall within the guidelines for fair use.

Instructors need to be aware of copyright and licensing status on all materials used in their courses. Copyright law must be considered before copying, retaining, or disseminating materials outside of the course. Copyright and fair use can be complicated, and faculty should check with campus librarians for guidance on where to locate the licensing status of all materials, and how to cite and state copyright permissions appropriately. It is a good idea to provide a copyright statement in your course, such as the following sample:

The materials used in connection with this course may be subject to copyright protection and are only for the use of students officially enrolled in the course for the educational purposes associated with the course.

All resources and materials in the course should be properly cited. In doing so, instructors and programs model good academic citizenship. This can guide students to respect the intellectual property of others and explore effective practices on publishing new materials.

Additionally, open-source materials (e.g., OERs/OSTs) are leveraged whenever possible. As defined by UNESCO, “Open Educational Resources (OERs) are any type of educational materials that are in the public domain or introduced with an open license. The nature of these open materials means that anyone can legally and freely copy, use, adapt, and re-share them. OERs range from textbooks to curricula, syllabi, lecture notes, assignments, tests, projects, audio, video, and animation.” OERs are available to support a wide range of disciplines and can take the form of complete textbooks, lectures, assignments, labs, simulations, interactive modules, projects, exams, animations, videos, games, and other course support materials.

- Review the Libraries webpages on Open Educational Resources and Copyright 101 and reach out to the liaison library with any questions.

- Learn how to incorporate Open Educational Resources in your course via the Open Washington OER Network course.

- Get inspired by OERs via Canvas Commons.

- Familiarize yourself with websites that provide open-source images and other content. The Office of Digital Learning and the Library can provide more information.

UNR Libraries resources:

McMurtrie, B. (2017, December 19). Use of Free Textbooks is Rising, but Barriers Remain. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

McShane, M. (2016). Open Educational Resources. Education Next, 17(1).

McKenzie, L. (2018, July 16). Free Digital Textbooks vs. Purchased Commercial Textbooks. Inside Higher Ed.

Watkins, D. (2017, February 23). Are Textbooks In or Out? The State of Open Educational Resources. OpenSource.

Zhadko, O., & Ko, S. (2019). Best Practices in Designing Courses with Open Educational Resources. Routledge.

4.2: Materials, activities, and assessments promote the achievement and alignment of course-wide objectives/SLOs.

Course objectives are specific, observable, and measurable as well as reflective of student learning across cognitive levels and express some level of mastery that students will be able to demonstrate as a result of participating fully in the course. Unless otherwise stated by their academic department, all University of Nevada, Reno syllabi should incorporate the UCCC-approved course objectives as provided in the UNR Catalog. All course content, learning activities, interactions, and assessments should be in alignment with these objectives/outcomes.

According to Quality Matters, “critical course components—learning objectives, assessments, instructional materials, learning activities, and course technology—reinforce one another to ensure that students achieve the desired learning outcomes. When aligned, assessments, instructional materials, learning activities, and course technology are directly tied to and support the learning objectives.” Materials, activities, and assessments meet the diverse needs of students, including the use of information from diverse sources and a variety of methods for students to demonstrate achievement of outcomes.

Overall, course objectives should be clearly communicated via the syllabus and course information documents, and measurable module-level objectives should also be introduced at the beginning of every module.

This standard can support Regular and Substantive Interaction (RSI) by providing students with opportunities to establish and discuss the relevance of the studied materials to their academic, professional, and personal lives. Giving students the opportunity to interact with the instructor to discuss their reasons for taking the course, prior knowledge of course discipline / content, and/or expectations for the course are all good strategies that can be accomplished in the design and activities of the course.

- Map out your course using the Office of Digital Learning’s course map template and/or with the aid of an ODL Instructional Designer to ensure that all activities, interaction, content, and assessments are meaningful and align with course-wide and program objectives.

- Explore Bloom’s Taxonomy and associated resources to better understand ways to measure success through outcome drafting and alignment.

- Complete the Applying the Quality Matters Rubric (APPQMR) certificate to learn more about how to assess and practice learning outcome/objective alignment with online course design.

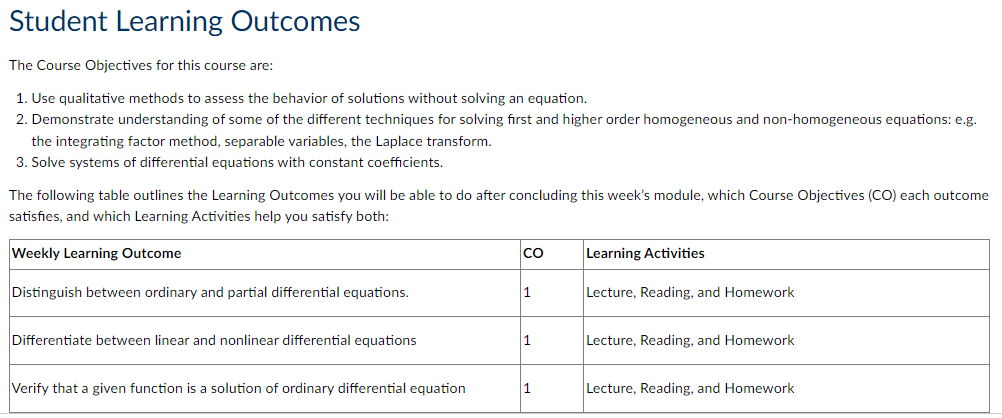

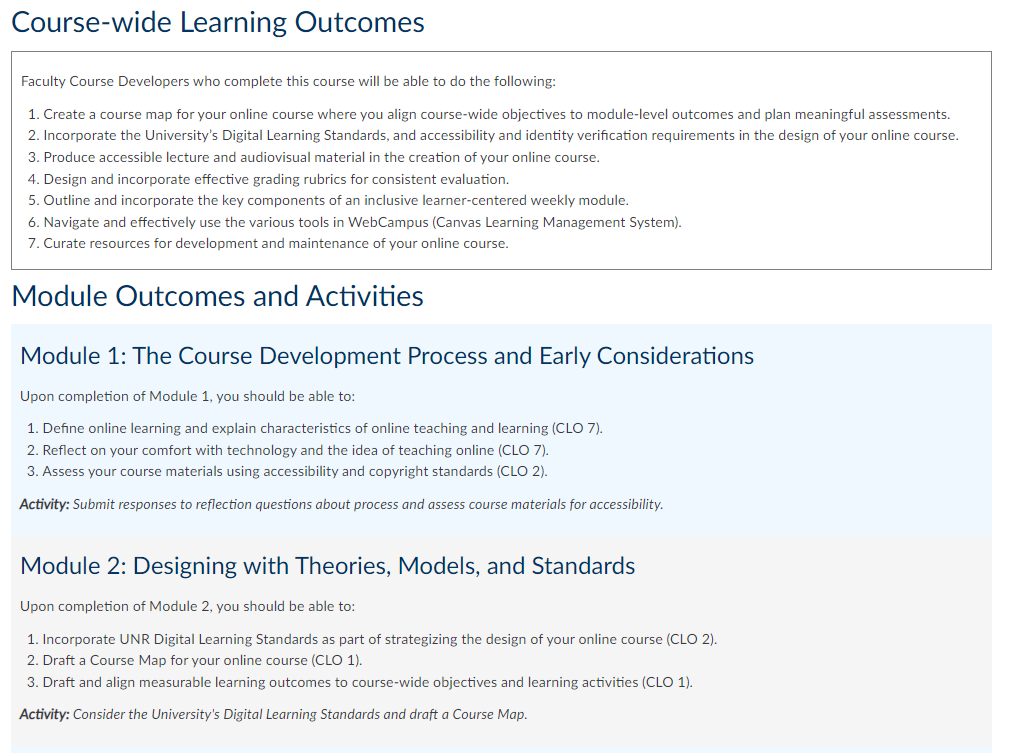

Student Learning Outcome alignment shared within the Overview page of a module. Module-level outcomes are measurable and aligned with course objectives and learning activities. Sample provided by Math Instructor Aleksey Telyakovskiy:

Portion of a Course Map shared in the course orientation module of the Office of Digital Learning’s Online Development Training Course, demonstrating how module-level outcomes are measurable and aligned with course objectives and learning activities for each module:

Course Mapping and Backward Design resources:

- Grant Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2015). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development. (The first edition of this text is available through the UNR Knowledge Center.)

- Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning. (2016, November 1). Course Structure Planning Guide Version 1.0. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne.

- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Backwards Course Design. Indiana University Bloomington.

- The Online Course Mapping Guide. (n.d.) Course Map Guide, Backward Design. Teaching + Learning Commons at UC San Diego.

- Teach Online. (n.d.). Guided Process for Using the Design for Online Toolkit. Arizona State University Teach Online.

- Center for Educational Innovation. (n.d.). Aligned Course Design. University of Minnesota.

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. (Eds.). (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman.

Bilon, E. (2019). Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Write Effective Learning Objectives. Edmund Bilon.

Dacko, et al. (2015). Making it Personal: Understanding the Online Learning Experience to Enable Design of an Inclusive, Integrated e-Learning Solution for Students. eLearning Papers, 42(1), 1–14.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses, Revised and Updated. Jossey-Bass.

SUNY Online. (n.d.) Design Effective and Accessible Online Activities, Interaction, and Assessments.

4.3: Adequate time is provided for students to complete and submit activities, and time requirements are clearly communicated.

Course activities and assessments are scaffolded and spaced throughout the course term to allow students time to properly digest information and build knowledge. Student workload and assessment submissions adhere to what is considered appropriate based upon department standards, course level, and UNR Definition of Student Credit Hour.

Understanding online instructional activity equivalencies is the first step to ensuring that you’ve provided adequate time for students to complete and submit activities. The Office of Digital Learning’s Online Course Contact Hours webpage provides a table that lists common instructional activities in the online teaching modality with a conversion into instructional contact time. Leveraging a teaching or learning taxonomy, such as Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy may also help ensure that course activities and assessments are scaffolded, spaced appropriately, and meet different levels of human cognition.

UNR resources:

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. (Eds.). (2000). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Pearson.

4.4: Frequent instructor communication is present throughout the course, enabling ample opportunities for students to engage with instructors.

Ample opportunities for interaction with the instructor should be built into course design (i.e., engaging in discussion-based activities, answering emails/messages quickly, Zoom, etc.) to mitigate distance and demonstrate social presence. When students understand the background/have a basic biography of their instructor, the “distance” between instructor and student is mitigated. Instructors who share personal narratives make a lasting impression on online students. Social presence is the ability of students to project their personal characteristics into the community of inquiry, thereby presenting themselves as 'real people' (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000). It relies on establishing a welcoming online learning space, as well as acknowledging students as valued members of the learning community.

- Send a warm and inviting welcome email/message/announcement.

- Create an About Your Instructor/Meet Your Instructor section that includes your preferred contact method, a brief bio, picture, or video of yourself, and how you would like to be addressed by your students.

- Establish early communication. Students need to perceive the instructor’s presence as soon as the course begins.

- Develop a positive social atmosphere. Model solidarity, congeniality, and affiliation.

- Reinforce predictable patterns of communication and action. Students need structured activity, repetition, and feedback. Without these, students will get the impression that the instructor does not care about the course or the students, making development of trust unlikely.

- Participate in icebreaker activities and introductory discussions.

- Respond to student inquiries within 24-48 hours.

- Provide substantial feedback on assessments.

This standard can support regular and substantive interaction (RSI) by building trust and a sense of class community. Getting to know the instructor (as well as their classmates) is a first step in building trust in an online class community. Instructors set this tone and climate at the start of the class by providing opportunities for students to engage and interact on a social and human level. By allowing students the opportunity to get to know the instructor in ways that are comfortable and appropriate for their discipline and personality, instructors can engage and model behaviors and interactions that will lead to a strong sense of online class community and trust among all course participants. Introductions, ice-breaker activities, and discussions that include some appropriate interactions and self-disclosures can be effectively designed to support the goals of this standard and RSI. For example, instructors can share their own personal academic and professional journey as it relates to the course topic.

Aragon, S. R. (2003). Creating Social Presence in Online Environments. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 100, 57–68.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87–105.

Hong, W. (2010, February 18) 8 Ways to Increase Social Presence in Online Teaching. Faculty Focus.

Kelly, R. (2008, August 11). Creating Trust in Online Education. Faculty Focus.

McGuire, B. (2016). Integrating the Intangibles into Asynchronous Online Instruction: Strategies for Improving Interaction and Social Presence. Journal of Effective Teaching, 16(3), 62–75.

Orlando, J. (2015). Methods for Welcoming Students to Your Course. Online Classroom, 15(5), 7–8.

Ryman, S., Burrell, L., Hardham, G., Richardson, B., & Ross, J. (2009). Creating and Sustaining Online Learning Communities: Designing for Transformative Learning. International Journal of Pedagogies & Learning, 5(3), 32–45.

4.5: Expectations for student interaction are clearly stated, including netiquette, grade weighting, models/examples, and timing and frequency of student contributions or participation.

Expectations for assignments, class participation, proctoring, due dates, group work, collaboration, and attendance requirements should be clearly articulated and easy to find and understand. Students expect and benefit from understanding the parameters and rationale of the learning activities in a course up front.

Outlining clear expectations for timing and frequency of interactions, activities, and assignments, as well as what type of standards should be upheld when working on particular activities, helps students to be successful and reduces frustration caused by ambiguity.

- Provide information on timing and frequency of contributions, models/examples, roles, and expectations for community standards.

- Provide detailed information on how student participation will be assessed or evaluated/graded, such as detailed grading rubrics.

- Reference University netiquette information and model respect in all online communications and collaborations.

SUNY Online. (n.d.). My Expectations Instructor Statement Example.

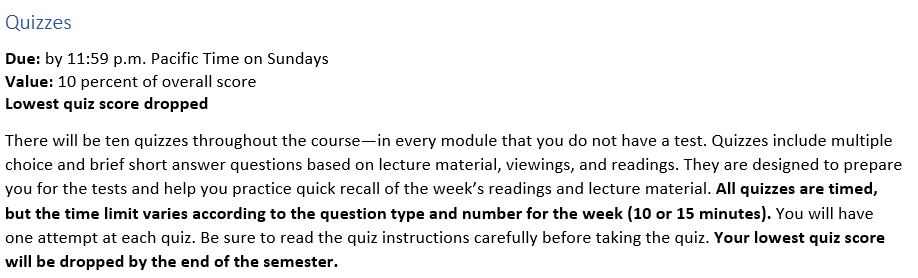

Sample Syllabus Quiz assignment description provided by Core Humanities, which includes due days and times, assignment value, whether the lowest score is dropped, and what to expect in each quiz assignment:

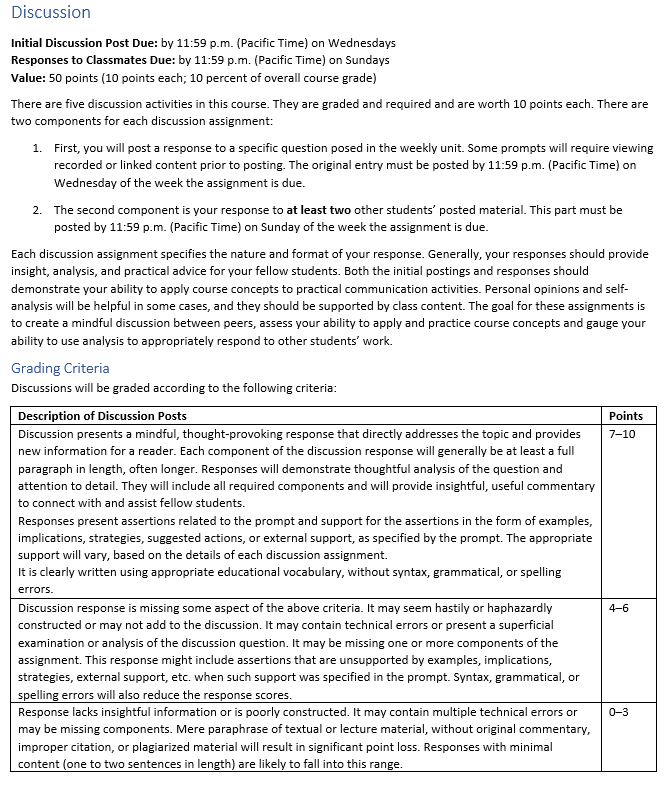

Sample Syllabus Discussion Information that includes due days and times for each discussion post type, assignment value, guidelines, and grading criteria. Example provided by Communication Studies Professor Saralinda Kiser:

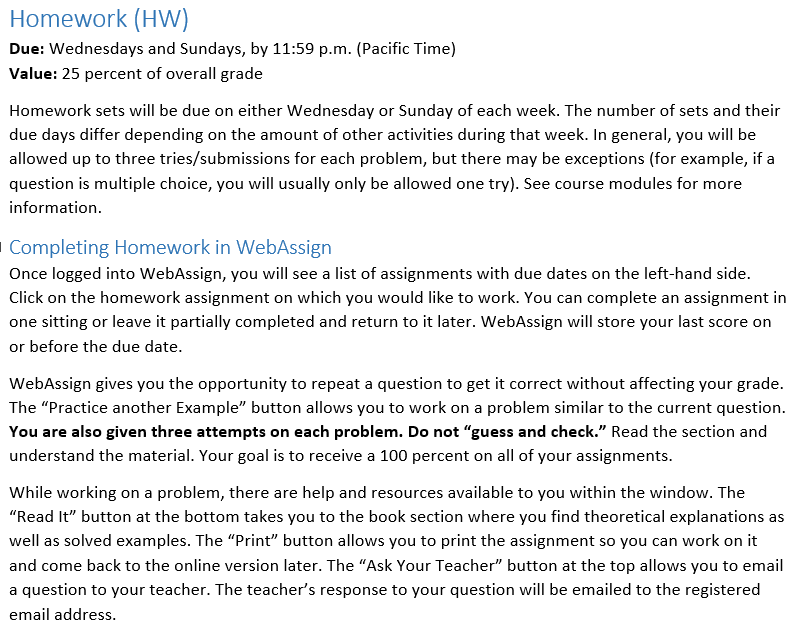

Sample Syllabus Homework Assignment description that includes information about the homework manager program the homework is completed in, number of attempts, how to ask for help, due day and times, and value. Example provided by Math Professor Aleksey Telyakovskiy:

4.6: Course offers opportunities for student-to-student interaction and constructive collaboration.

Collaboration in a digital course fosters constructive learning by enabling students to be active participants, take initiative, think critically, and engage each other in dialogue. According to Lee and Choi (2011), the more instructors promoted interaction through collaboration, feedback, group activities, and peer scaffolding, the more likely that students persisted and successfully completed their online studies.

When students engage with one another, it requires them to assume more responsibility for their own learning, which often leads to a deeper level of engagement. The instructor’s role is as a facilitator, who moderates and evaluates the quality and quantity of interaction between students. Additionally, group and peer-review assignments can support social, teaching, and cognitive presences in the online learning environment.

Student-to-student interaction and constructive collaboration is supported by the Online Collaborative Learning (OCL) Theory, created by Dr. Linda Harasim of the University of Toronto in 1983. In this model of learning, students are encouraged and supported to work together to create knowledge, and the instructor plays a key role as a fellow learner and a link to a knowledge community. Learning is viewed as a social process and knowledge is viewed as socially constructed.

- Create collaborative activities and peer assessments, which require trust and a strong sense of class community for success.

- Develop Online Cooperative Learning Activities

- Use online interaction/discussion strategies that have a positive impact on learner outcomes:

- Open-ended prompts (like brainstorming questions)

- Graded discussion posts

- Focused discussions, which center around one specific topic

- Elaborated feedback, which provides explanations, or additional resources, like hints and extra study materials

- Student led discussions: Assign a different learner to moderate the discussion forum each module, helping other students stay on topic and on track.

- Hold a formal debate in the online discussion forum.

- Integrate case studies that involve group scenarios into discussion forums. Have students role-play the scenario and then reflect on the decisions of their classmates.

- Assign collaborative writing projects with dyads (pairs) of students and have them work together as a team throughout the term.

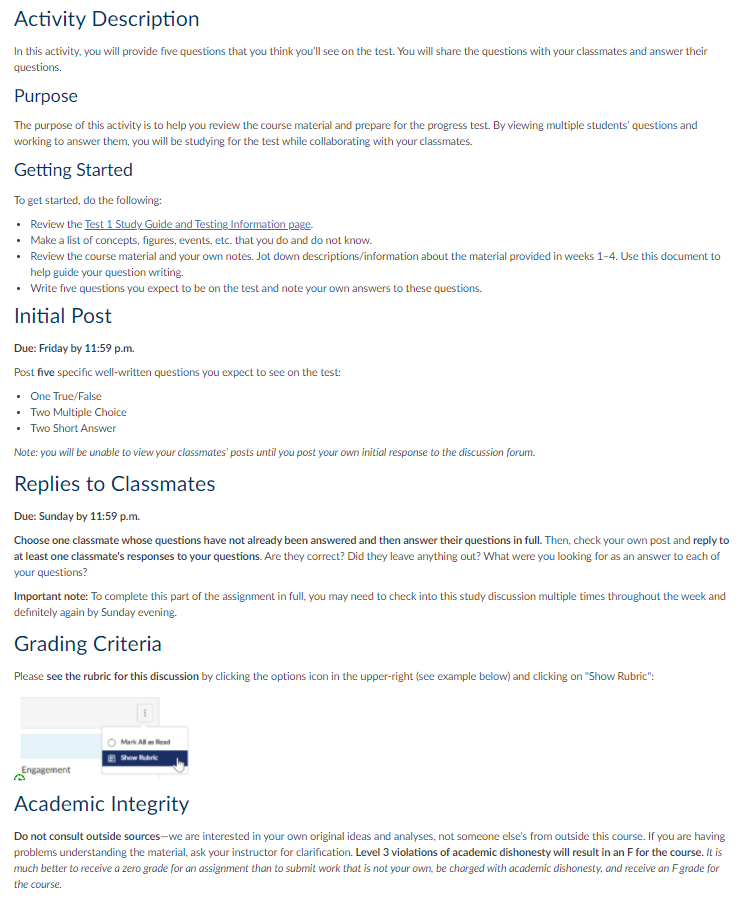

Discussion example whereby the discussion forum is used as a place to study for the upcoming test. How to get started, where to find more information, the purpose, grading criteria, instructions for each type of reply, and due days and times are all provided. Example provided by Core Humanities Instructor Angela Chase:

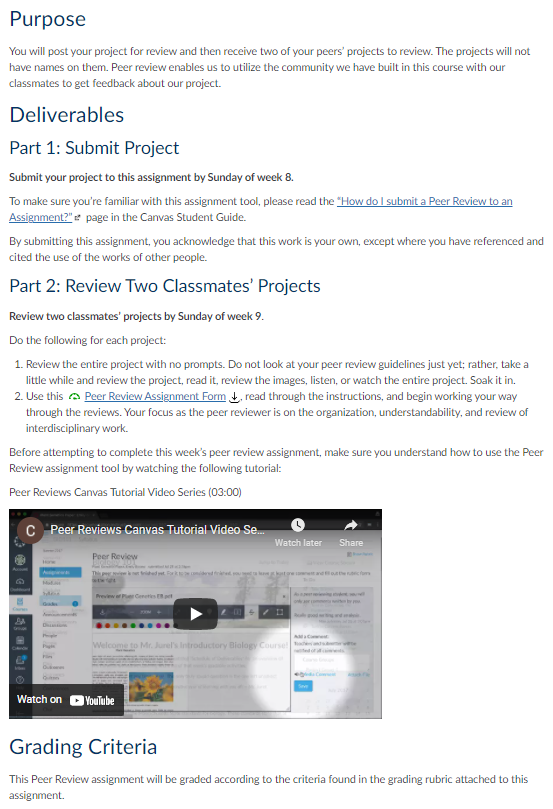

Peer Review assignment example where purpose, deliverables, due days, grading criterial, example tutorials, links for help, and exact instructions for each part is provided and explained. Example provided by Interdisciplinary Studies Instructors Emilly Borthwick-Wong and Kara Spracklin:

UNR Resources:

- Engagement Strategies

- Communication Strategies and Communication Tools

- Discussions and Discussion Strategies

- Collaborations Strategies and Collaborative Tools

- Peer Review and Peer Review Strategies

Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2005). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty. Jossey Bass.

Bates, A.W. (2019). Chapter 4: Methods of Teaching with an Online Focus – Online Collaborative Learning. In Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning (2nd ed.). BC Campus Open Text.

Lee, Y. & Choi, J. (2011). A Review of Online Course Dropout Research: Implications for Practice and Future Research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59, 593–618.

Lee, J. E., & Recker, M. (2021). The Effects of Instructors’ Use of Online Discussions Strategies on Student Participation and Performance in University Online Introductory Mathematics Courses. Computers & Education, 162.

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (2007). Building Online Learning Communities: Effective Strategies for the Virtual Classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Robler M.D., & Ekhaml, L. (2000). How Interactive are Your Distance Courses? A Rubric for Assessing Interaction in Distance Learning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 3(2).

Teaching Online Pedagogy Repository. (n.d.). Facilitate Discussions Effectively and Establish a Group Discussion Strategy. University of Central Florida.