The dirt roads of Guatemala are not always inviting, particularly when you are part of a group of 16 volunteers and students tightly loaded into three trucks.

For Miles Becker, however, some long stretches of rough road were not about to inhibit the task at hand, which was to visit three rural Guatemalan villages and the small town of Lupina in early January, in an effort to help the residents improve their water services.

“It was definitely remote,” said Becker, a Ph.D. student at the University of Nevada, Reno in the Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology program. Becker traveled to Guatemala as part of the campus’ student organization, the Student Association for International Water Issues (SAIWI). “We traveled on this little dirt road that most people in Reno probably wouldn’t want to be on.”

Yet Becker and his cohorts, including seven students from the University, one from UNLV, as well as faculty advisor Keith Dennett, an associate professor in civil and environmental engineering, knew exactly why they were visiting Guatemala.

Lupina, the town of about 450 households where the group spent the majority of its time, was a study in contrasts, Becker said.

“It’s actually fairly advanced in some ways,” Becker said, noting that many residents traveled on motor scooters or in pickup trucks, and that several of the concrete-block homes had radios and television.

On the other hand, however, was the town’s other reality. Even in a region of the world where rainfall can be plentiful, freshwater – for homes that were little more than a single room, with as many as eight people living in such cramped quarters – was hard to find.

“Even though rainfall is relatively abundant, many people are without access to a secure water source,” Becker said, noting that about half of Guatemala’s 13.6 million population lives in small rural communities with limited opportunities to improve water services.

When a smaller group from SAIWI had visited the same area in July, it was determined that 31 rainwater harvesting systems could offer a partial solution to the problem. The work would be difficult, but Becker and his fellow students were anxious to get started.

As Becker recalled later, “When you have a chance to help people that have nothing compared to what we have here, it’s an amazing opportunity.”

CONNECTING RENO’S KNOW-HOW TO LUPINA’S NEEDS

The story behind Becker’s SAIWI trip to Lupina is a classic case of the world is flat and certainly much smaller than any of us could ever believe.

It’s similar to how translation during the trip was accomplished, where the SAIWI students’ interpreter, Daniel Portillo, would converse with the local residents in their preferred Mayan dialect, Popti, then translate the words into Spanish, which would in turn be translated to English.

“It was like a little train going back and forth,” smiled Becker, an avid outdoorsman who grew up in upstate New York, attending Cornell University in his hometown of Ithaca, N.Y., as an undergraduate. Becker’s love of the outdoors was one of the reasons why he chose the University of Nevada to seek his Ph.D.: “One of the biggest draws of all was being this close to the mountains and Lake Tahoe. I had been working in Michigan and Texas before. Having the mountains here, I have to be honest with you, that was a big draw for me.”

So it was several months ago, when the “little train” of communication connected the mountains of Reno to the forests of Lupina.

A Reno couple, Mark and Clem Glenn, had contact with the villagers of Lupina. The Glenns, in turn, knew a Reno engineer named Cathy Fitzgerald, a rail-thin ultramarathoner and former UCLA basketball player who has made volunteering in third-world nations one of her life’s callings.

“Cathy’s been hugely instrumental for the group and has participated in SAIWI trips for the past six years,” Becker said. “She’s the type of person who will spend a week in Africa digging a well.

“That’s her idea of a vacation.”

Fitzgerald suggested that the Glenns contact SAIWI. From there, the mechanics of the trip were put into motion. The survey trip in July unearthed some disheartening news. The residents of Lupina had access to a clean water supply, but the water supply was being cut off every few days. Demand was outstripping supply by a large margin.

“They were getting access to water only two or three days a week,” Becker said. “They were interested in finding a different access to water. So we came up with a couple of solutions, and implemented them (in January).”

The enthusiasm of the students, coupled with Dennett’s engineering expertise, ensured that the project would proceed smoothly. Another couple, Robin and Steve Braun of Strong Tower Ministries, offered the students a chance to work on a couple of other projects before the group arrived in Lupina. Becker said the Brauns have lived and worked in Guatemala for the better part of a decade, offering health services and water resources aid for three small, isolated communities in the northwestern corner of Guatemala in the Zacapa region.

In the village of Liquidambo, the group perforated stabilizing concrete in a wall of a hand-dug well to make it more productive and hung a slightly sloping gutter from one side of a school to capture runoff and collect it in a large storage tank. In the valley below Liquidambo, in the village of San Antonio, the SAIWI group constructed rainwater harvesting systems on three houses. Each morning, Becker remembered, the group’s work was serenaded by a local rooster. “Several hours before dawn,” he added. In the final village, El Morrito, they replaced a crushed large water storage tank.

MAKING CONNECTION IN LUPINA

Two days later, Becker and his fellow travelers arrived in Lupina.

“In Lupina, we were hosted by a local family (the family of Jose Mendoza),” Becker recalled. “So the kids (eight in all) were particularly curious and very interactive, and wanted to play a lot of games. There was a real connection there. They knew Cathy from her visit in July, which made it kind of special.

“It was very playful and very open; the kids were great. The family’s youngest son really liked Cathy. I have this picture of her with flowers in her hair.”

Then Becker grinned conspiratorially, the thought of a former basketball player at UCLA having her head adorned with colorful flowers: “Cathy told me, ‘Don’t ever show that anyone.’”

Flowers and smiles aside, the work was challenging, yet energizing.

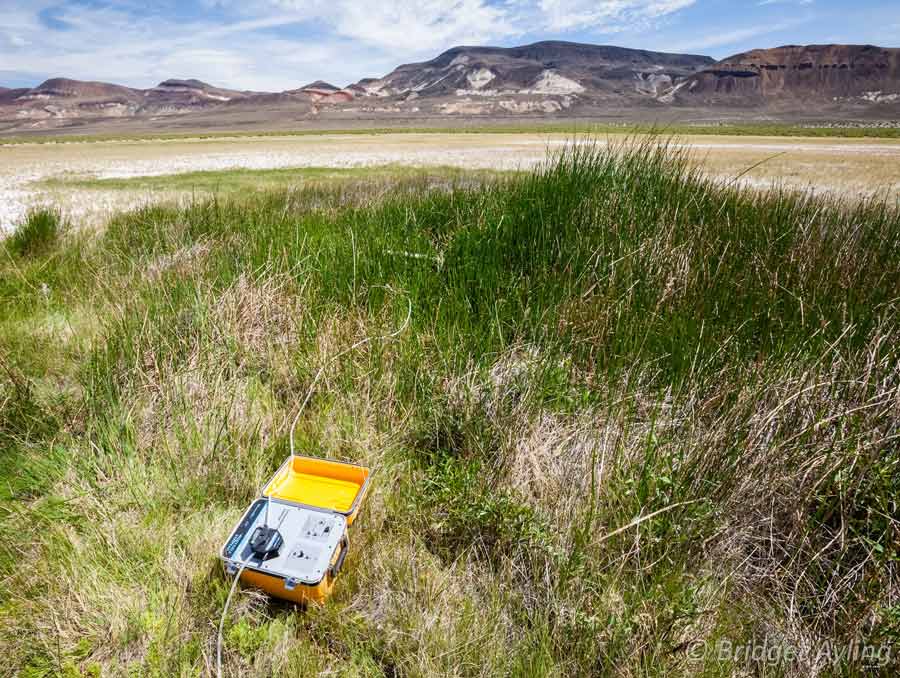

It was determined that the small spring servicing Lupina had a flow rate of 220 liters per day, far too low to meet the town’s needs. To bridge the gap, 28 five-feet-in-diameter, five-foot-high, 1,700-liter rainwater harvesting systems were to be made operational.

“It was definitely very busy,” Becker said. “We really cranked it out. We cranked out systems for four churches, two schools and 22 homes. We did that in five or six days. We got a lot done in Lupina, that’s for sure.”

As much as he felt a strong sense of satisfaction about the work, Becker said he couldn’t help but also feel a strong sense of kinship with the citizens of Lupina. He remembered one of the slower moments, when the SAIWI group was still waiting for the tanks to arrive. The group moseyed to the town’s soccer field. Vendors sold fried chicken and papas fritas. The people sipped soft drinks and beer. Music blared from a loudspeaker, and, Becker remembered later, “drowned out four men playing marimba (a lively musical instrument where keys or bars are struck by a mallet) behind one of the goals.”

Recalling that moment, and others like them, when curious, smiling children were attracted to the SAIWI work like happy moths to a flame, or when thankful villagers gave the students bags of roasted peanuts from the recent peanut harvest as a token of their appreciation, or when the town’s water committee held a meeting on the best course of action to follow, and about 100 people actually showed up to voice their various raucous opinions, all of it, in Becker’s mind, “fairly Democratic and fairly organized,” came to symbolize something much more profound.

“It’s a really powerful thing, to have the opportunity to have an experience like that,” Becker said. “These are families that are living in a one-room house and to do something that to us is really simple but to them makes a huge difference in their life … to know that what you’ve done is going to greatly increase their standard of living … it really does help put your own life in perspective.”

Becker, who is studying avian ecology, and in particular is looking at the responses of birds to urban development, is convinced more than ever before that all spaces in the world are important.

He’s a fan of green space, of course, and he’s come to understand how good things can come together for the good of all, for the betterment of a community, of a small town, of a village.

Whether he is checking field sites of bird nesting areas along the Truckee River, or sitting in a cramped truck bouncing down the rough back roads of Guatemala, Becker knows now there are more similarities than differences in the world.

“Everything we do,” he said, “is connected.”