College campuses do not lack for talent. Nor do they have a shortage of ideas or innovation.

Yet somehow along the way, the harnessing of knowledge and discovery on college campuses and then hitching these prized commodities to the needs of the business community for economic development is never a sure thing.

For economic development to truly succeed, University of Nevada, Reno President Milt Glick said Monday during his keynote address at the University Economic Development Association national conference, hosted in Reno by the University’s College of Business and Nevada Small Business Development Center, “a great interaction” between communities and universities must occur.

Glick cited examples in San Diego, Calif., and Seattle, Wash., where a major research university certainly was a driving force but was not the only factor in strong economic redevelopment efforts.

In the case of UC-San Diego, Glick said intense personal connection was established between university researchers, alumni, business community and state leaders. This led to a technology-based economy sprouting in the early years of the 21st century.

“It was literally the right people hosting cocktail parties, getting together, networking at every opportunity,” Glick said.

For Seattle, Wash., the creation of what Bill Gates, Sr., has termed the “most educated city in America” came about as the University of Washington produced creative and ambitious graduates who in turn fueled the cutting-edge businesses of the knowledge economy. But UW did not produce sufficient graduates to fuel the economy. Rather, the high-value businesses UW attracted to the area brought that talent from around the world.

“It was not all of the great technology that came out of a great university,” Glick said. “Rather, it was a great university with tremendous talent that attracted bright, innovative, risk-taking individuals who gathered their businesses around the university and the Seattle area.

“The university helped attract the educated workforce across the country and the world. In both cases, it was the presence of great universities (that helped).They served as a catalyst for their communities.”

Glick said that for any university, “the critical link” in developing a strong base for potential economic development lies in its faculty.

“I think faculty are our most treasured part of our university,” he said. “They are very smart, they are driven to compete at the highest level, and they are also driven to do good.”

Yet, Glick encouraged those in the audience to think of a new framework for linking faculty more tightly with economic development.

“(Faculty) are not mentored on how to take a discovery to the marketplace,” Glick said. “We have to help them turn their ideas into economic reality.”

Glick said he has a “realistic” view of technology transfer, through which discoveries are moved into the marketplace. On the one hand, the instances of a university hitting a “home run” in technology transfer are well-documented, from the University of Florida’s creation of Gatorade to the University of Wisconsin’s Vitamin D irradiation discoveries. Even with the long history at Wisconsin, 70 percent of royalties to the university derives back to a 1920s vitamin D discovery.

Yet such historic examples often “over-fuel” expectations, Glick said.

“Tech transfer needs very large portfolios of many technologies to be effective,” Glick said. “Most of us can’t afford that kind of tech transfer office.”

He cited a 2009 national tech transfer study showing that universities with $100 million in externally funded research have a 1 in 5 chance of simply breaking even for such initiatives.

“Tech transfer is still the right thing to do,” he said. “We do it because if we have a discovery that can be made useful, it is a central responsibility of a university to make it useful.”

One of the keys to maximizing tech transfer, Glick said, is focusing it in areas that are of benefit to the communities and states which universities serve. He singled out state of Utah’s “U-Star” initiative, which has seen more than $200 million in state support go to attract focused teams of research at the University of Utah and Utah State.

Such an effort has put the state of Utah “on the forefront” of economic development in the country, Glick said. He pointed to the recent news that the University of Utah has now matched MIT as the nation’s leader in creating new businesses.

Glick also used several examples from the University of Nevada, where faculty-led innovation has resulted in business development either from University-created technologies or through the efforts of graduates who learned such technologies while at Nevada.

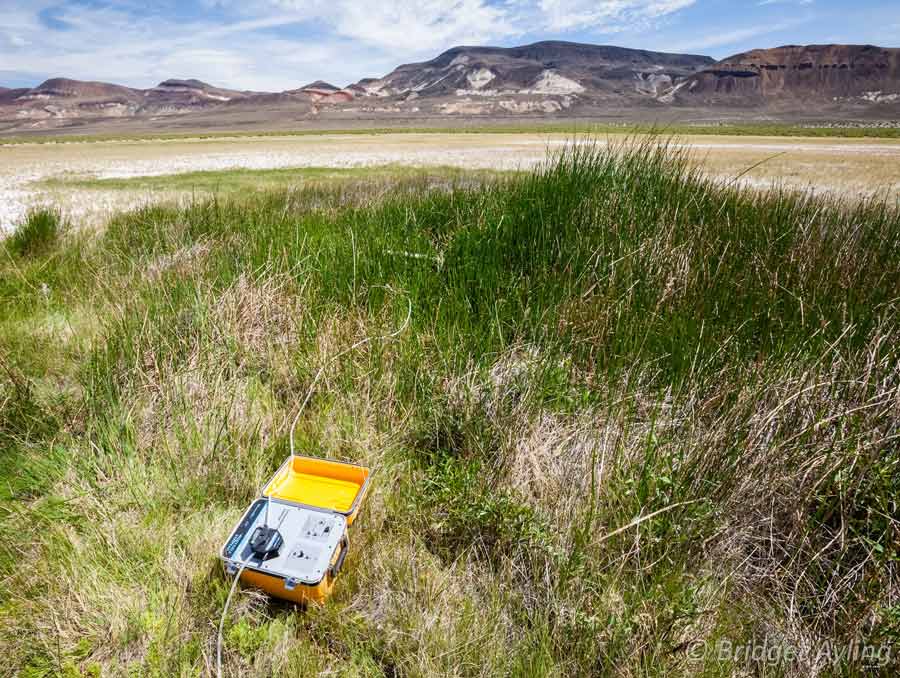

Citing work in seismology technology for geophysical applications through the local company Optim, among others, Glick said the University-spawned companies were based on the kind of “serendipitous research that has created the new economy.”

And as much as new technology creation remains the goal of many universities, Glick cautioned all in attendance to never forget the human part of the economic development equation.

He told the story of University Provost Marc Johnson, who in recent months has developed a promising new “one stop shop” initiative with the state’s mining economy.

“We’ve always been a ‘go-to’ place for the mining industry to find its mining engineers, but we realize the mining industry needs a lot more,” Glick said. He said Johnson has twice traveled to the state’s mining capital in Elko, bringing with him the deans of the University’s colleges of business, science, engineering and agriculture.

“Marc has twice taken these trips to meet with the leaders of our mining industry to help us design what the mining industry needs … not just in Nevada, but throughout the world,” he said.

For Glick, the effort of his provost was just another example of the University finding the “right front door” for the business community to enter in its relationship with higher learning.

“In my view,” Glick said, “the single most important thing we do (in the economic development equation) is to create an educated workforce. All of us know that we will not enjoy the same kind of quality of life if we don’t produce an educated workforce.”

More than 170 university economic development professionals from across the country attended the conference at the Eldorado Hotel Casino Nov. 7-9. Representing the University as panelists were Greg Mosier, College of Business dean; Brian Bonnenfant, Center for Regional Studies director; and Tom Harris, Center for Economic Development director. Attendees visited the Mathewson-IGT Knowledge Center Nov. 8 for the conference’s “Student Entrepreneur Experience” reception, and the work of the Nevada Small Business Development Center, based in the University’s College of Business, was profiled at the conference’s “Showcase of States” trade show.